A New Biography of an Old Master ■ by Brandon Cook

The publication of Gordon Bowker’s new biography of James Joyce, last year in Great Britain and this year in the United States, did not occur on a particularly auspicious date — a fact that might very well have set the famed Irish writer quivering in the fear of bad juju.

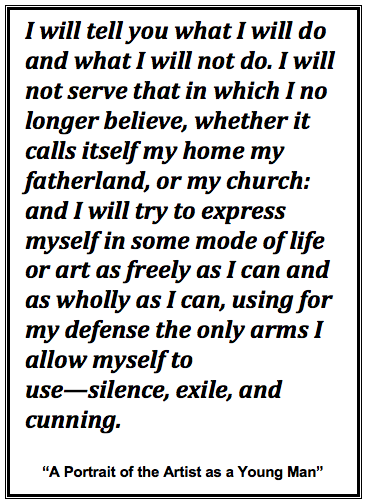

In 2011, the most renowned literary figure of the 20th century celebrated his 129th birthday. A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, the work that gave Joyce his definitive claims as a modern literary icon, turned 95 while Ulysses, the perennial “greatest novel ever written” but more commonly known as a bane to book clubs, required reading lists, and ambitious readers, marked its scorching debut 89 years ago .

Seventeen years went by after that, through which Joyce suffered the treatment of his schizophrenic daughter, a milieu of crippling debts, and the outbreak of the Second World War, not to mention years of 16-20 hour workdays. At the end of these travails came Finnegans Wake, a volume so dense with linguistic erudition (there are a purported 60 languages at work) and cultural polytonality that even the writer’s closest disciples abandoned him. Ezra Pound, that quintessential mad genius with Lucifer beard and manic eyes who first serialized Ulysses in his magazine, promptly abandoned the writer with the claim that he was wasting his genius. Joyce, spurned by readers and critics alike, mentally flushed and physically exhausted, died less than a year after its publication.

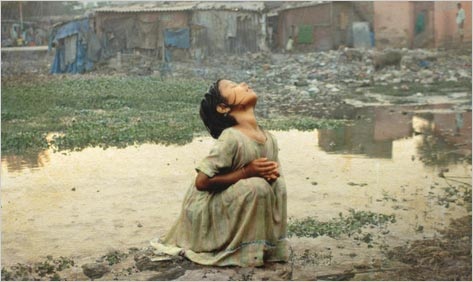

Sylvia Beach, Who Published Ulysses, And James Joyce

■

Faced with these ostensibly random dates, it’s curious that Bowker believes that now is the time that we need a new perspective on Joyce to merit an all-inclusive biography. Any serious devotee of the Irish writer, when asked about biographical material, will point immediately to the 1959 work by Richard Ellmann (revised in 1982) as the source from which the purest Joyce flows. Novelist Anthony Burgess even dubbed it the “greatest literary biography of the century,” and all those who have read it are inclined to agree.

Ellmann foregoes the listing of dry fact and spurns the tired, pedantic diction that dispels so many readers away from biography. Equipped with the unequivocal mastery of language, his subjects yearn to speak for themselves and unlike most writers Ellmann is able to let them do so. The numerous letters, journal entries, and corresponsive limericks that Joyce shared with his acquaintances and that Ellmann picked, painstakingly, like grapes from the vine, provide a portrait of the artist in three crystal clear dimensions.

But Ellmann is a rare case, with a passion centralized on Irish modernism and little else. The biographer, sensing Ireland’s literary revolution when he produced his first two volumes on Yeats, ended up serving all four of the nation’s masters: Yeats, Joyce, Beckett, and Wilde, for which he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize.

By no means does Bowker’s biography attempt to outdo Ellmann’s and this is a good thing. There are obvious nods to the master text when he borrows from it, liberally quoting the same anecdotes, exclamations, and even textual interpretations (his rendering of young Joyce’s Et Tu Healy reads almost verbatim). His portraits of the Joyces owe much to Ellmann’s conception as well. Father John Joyce begins the text highlighted as a witty Parnellite while adoring Stanislaus fervidly dog tails and copycats every action of his older brother James, from his precocious interests in literature to his dramatic sundering with the Church (Stanislaus, in typical little-brother fashion, took the action too far and abandoned God whereas James merely abandoned man’s corrupted perception).

Bowker’s eye for detail serves him well in many of his corresponding episodes with Ellmann. One such episode takes place with Joyce’s former medical peer, literary admirer, and one-time roommate Oliver St. John Gogarty, forever immobilized to readers of Ulysses as the doggedly cynical, “stately plump Buck Mulligan.” Each biographer lets the reader know that this literary eternity was a fate the young Buck had coming to him. Following recent quarrels in their already strained relationship, in 1904 the destitute Joyce nevertheless allowed himself to be housed in Gogarty’s ridiculous, militaristic Martello Tower along with one of his lackeys, Samuel Trench (Haines in Ulysses). Trench, prone to horrible nightmares and screaming fits, kept a loaded gun by his side. It was during one such terror that he awoke and, in hysterics, fired his gun several times against the back wall, narrowly missing the startled Joyce. Bowker, preferring a continuation of this scene, asserts that Gogarty later awoke and repeated the gesture as a ruse so that the brooding, disdaining Joyce would move out of the tower.

Joyce

■

Unfortunately, many of the relationships become increasingly dense with Bowker’s chunks of fact-driven prose. When John Joyce begins to decline from amiable jokester to failed father and hapless drunk, the tragic loss of his verbal wit to the consumption of spirits (which so hauntingly foreshadows James’s future struggles) can easily pass the reader unregarded. Ellmann, who quotes from John’s brilliant pub chat and ample limericks that he shared with James, presents a far more life-loving spirit than Bowker.

So it goes for many of the dynamics that exist in the relationship between Stanislaus and James. Bowker’s description of the brothers’ intermittent stay in Trieste between the years 1904 through 1920, fails to capture Stanislaus’s complex and contradictory emotions. Summoned in order to provide company to James’s beloved Nora while he completed Dubliners and A Portrait of the Artist, Stanislaus arrived enthusiastic, only to become one of the countless many from whom Joyce would siphon money to pay for lavish meals, tips, and shopping sprees. Readers will wonder why he suffered his pockets to be picked for as long as he did, to which Bowker meekly posits filial duty and admiration for James’s talents. What’s missing is Stanislaus’s fascinating diary, wherein the brother records how his duties to the capricious James reflect a greater duty to literature itself. James’s lauding as ‘literary genius’ did not spring from the Pound/Yeats/Eliot brigade, but from wholesome, second-best Stanislaus.

James fairs better under this at times toilsome prose, but not by much. In the midst of the controversy surrounding the Ulysses publication, Bowker writes that Joyce was “becoming [more] famous for being spoken and written about than for being read.”

One is tempted to think that the biographer might take note and allow more of the authentic Irishman to be heard, instead of reining him in and paring his statements down to increments seldom exceeding three or four sentences. Joyce, in several documents, provides the best interpretation and criticism of his work anyway, showing that once freed from the words of intellectuals and pedagogues, the text is actually much simpler and accessible to the reader than before. Such is true of the Nausicaa episode, in which the resting Bloom pleasures himself to the exposed stockings of the simple-minded soubrette Gerty McDowell. Joyce writes the chapter in what he calls “namby-pamby jammy marmalady drawersy (alto là!) style.”

A part of the author seems to want to keep its figure shrouded in mystery. How does the man who guffawed boomingly at farts and funny-sounding words become the century’s literary mastermind? Why did this man, who once scooped up dirt and declared it in a hushed reverence to be “wonderful,” continually empty his pockets for a life of inflated decadence? How did a mind whose contents more often resemble the residue found in a vacuum cleaner bag grapple with man’s most sprawling questions? Bowker may have the answers but he won’t say so, just as he won’t allow Joyce out of the lenses of his scope.

Even so, there is at least one moment when this tactic is beneficial to the reader. Finnegans Wake is treated by Bowker with bold hypotheses and then tidily explored: something for which more readers are likely to clamor than the confusing textual excerpts that Ellmann offers or the expansive Finnegans Wake Skeleton’s Key by Joseph Campbell

Contrary to the belief that the unconscious ‘dreamscape’ of Finnegans Wake, (Work in Progress as it was known until publication) was the natural point of development from the monologue intérieur of Ulysses, Bowker asserts that Eliot’s The Waste Land is the true inspiration, providing the “fractured” and “unstable” form while encouraging the necessity of the various portmanteaus. It’s a valid argument that one may push further, contrasting even the drought and dearth of Eliot’s parched, dead ground with Joyce’s cyclical “riverrun” of life, the river Anna Livia Plurabelle.

There are other such strong scenes upon which Bowker lingers that other biographers have passed by. This is the outbreak of World War II. Ellmann dismissed it as Joyce did: unrelated to and disturbing the production of art, and therefore unworthy of much consideration. Bowker’s war blazes across the book’s last thirty pages, reminding the reader that Joyce’s singular artistic obsessions, admirable in their way, were nevertheless far from realistic. Lucia, his schizophrenic daughter, was being treated in a French mental hospital during Nazi occupation of the country and could not be brought out despite the family’s frantic efforts. Joyce could forget about the war, but the war never forgot about Joyce.

One of the most poignant scenes in the biography occurs in the beginning of the now-famous treatment of Lucie in the early 1930’s, when Joyce’s obsessive work on Finnegans Wake had to be halted so that his daughter could receive treatment for a condition the doctors would only say was baffling (and still is; perhaps the most accurate diagnosis came from Joyce himself, who believed she was suffering a combination of megalomania and an inability to transform artistic vision into reality). Years of doctor-hopping and expensive bills had got the couple nowhere and only after much pressuring did Joyce reluctantly agree to treat his daughter with the psychoanalyst Carl Jung, an admirer of Joyce’s genius who ambiguously declared that Ulysses “could be read the same backwards as forwards.” The meeting of these two mental geniuses reads as two wolves sizing the other up; for the palpable tension Bowker quotes Jung: ‘ “it was impossible not to see and feel his resistance.” ‘

“There is nothing your hand wants to reach for except a volume of Joyce,” reads Chris Proctor’s endorsement on the biography’s dust jacket. This rings truer than one might expect. Bowker’s book still manages to provide small insights that one will not find elsewhere. Less so than Ellmann, the book is effectual. One will look to Joyce afterwards and see that nowhere else in the English language can such humor be drawn from words, and such powerful life as from Molly Bloom’s final, affirmative “Yes.” Bowker’s biography breathes no new life into Joyce but the reader cannot expect this. The 20th century’s greatest literary innovator needs no new life–he resonates with as much vitality today as ever.

■

The Ryder, January 2013

Photo caps (Joyce in bookstore)

Sylvia Beach (who published Ulysses) and Joyce in the Shakespeare and Company bookstore in Paris.

Photo cap (Beach and Joyce standing)

James Joyce and Sylvia Beach (who published Ulysses) outside the door of Shakespeare and Company on the Rue de l’Odeon in Paris in 1920

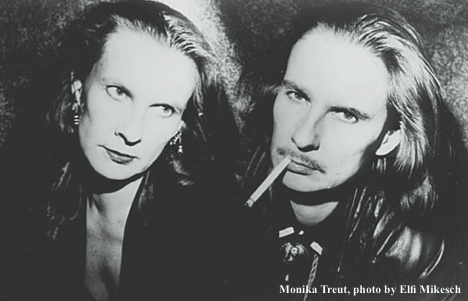

Use one of these bookstore pictures and or/one of the posed headshots.

I’ve also attached two versions of the bookcover. I don’t think the bookcover or the headshots require photo caps. And I’m not sure it’s necessary to reproduce the book cover – neither image does much for me, although I’m certainly not opposed to using one of them as space permits.