God and the Devil, like gospel and blues, are never far apart in Charles Burnett’s film

By James Naremore

[editor’s note: James Naremore is Chancellors’ Professor of Communication and Culture, English, and Comparative Literature at Indiana University. He has published acclaimed books on the films of Stanley Kubrick, Orson Welles and Alfred Hitchcock. What follows is an excerpt from his forthcoming book, Charles Burnett: A Cinema of Symbolic Knowledge (University of California Press), is the first to be written about Burnett. “I aimed for comprehensiveness,” he explains, “and because many of his films are difficult to see, I tried not only to give them the critical attention they deserve but also to describe them in detail for those viewers who may be unfamiliar with them.”]

Author’s introduction: Charles Burnett, one of America’s most important yet least widely known filmmakers, was born in Mississippi in 1947, but his family soon took part in the post-war Southern Black diaspora, settling in the Watts area of Los Angeles. After attending Los Angeles Community College, Burnett entered UCLA, where he became the leading figure in a relatively short-lived film movement known as “the L.A. Rebellion.” His MFA thesis, the 16mm Killer of Sheep, (filmed 1973-75, exhibited 1977), was shot on weekends with locals in Watts and is arguably the greatest student film ever made: it’s listed as one of the 100 essential pictures by the National Society of Film Critics, and was one of the first motion pictures to be officially designated a National Treasure by the Library of Congress.

Among the reasons why Burnett’s subsequent career hasn’t achieved larger public attention is that his films grow out of his experience as a working-class Black, and he doesn’t traffic in sex, violence, or glamor. In thematic terms, he has more in common with a playwright like August Wilson than with Spike Lee. There’s nothing obscure or arty about his work (some of his pictures are straightforward history lessons aimed at kids), but he isn’t the kind of director who appeals to your average Hollywood producer. An authentic independent, he has great integrity and has been faced with all the disadvantages and disappointments such a position entails. But no filmmaker has a better record of showing why Black Lives Matter. Among his important films for the big screen and TV are To Sleep with Anger (1990, a masterpiece about generational conflict within a Black family, unavailable on American DVD for decades), The Glass Shield (1994, about police violence and murder of Blacks in Los Angeles), Nightjohn (1996, about Southern slavery, told from the point of view of a child), Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property (2003, about the Turner rebellion, and in my view the best treatment of the subject in any medium), and Warming by the Devil’s Fire (2003, about blues music, discussed below).

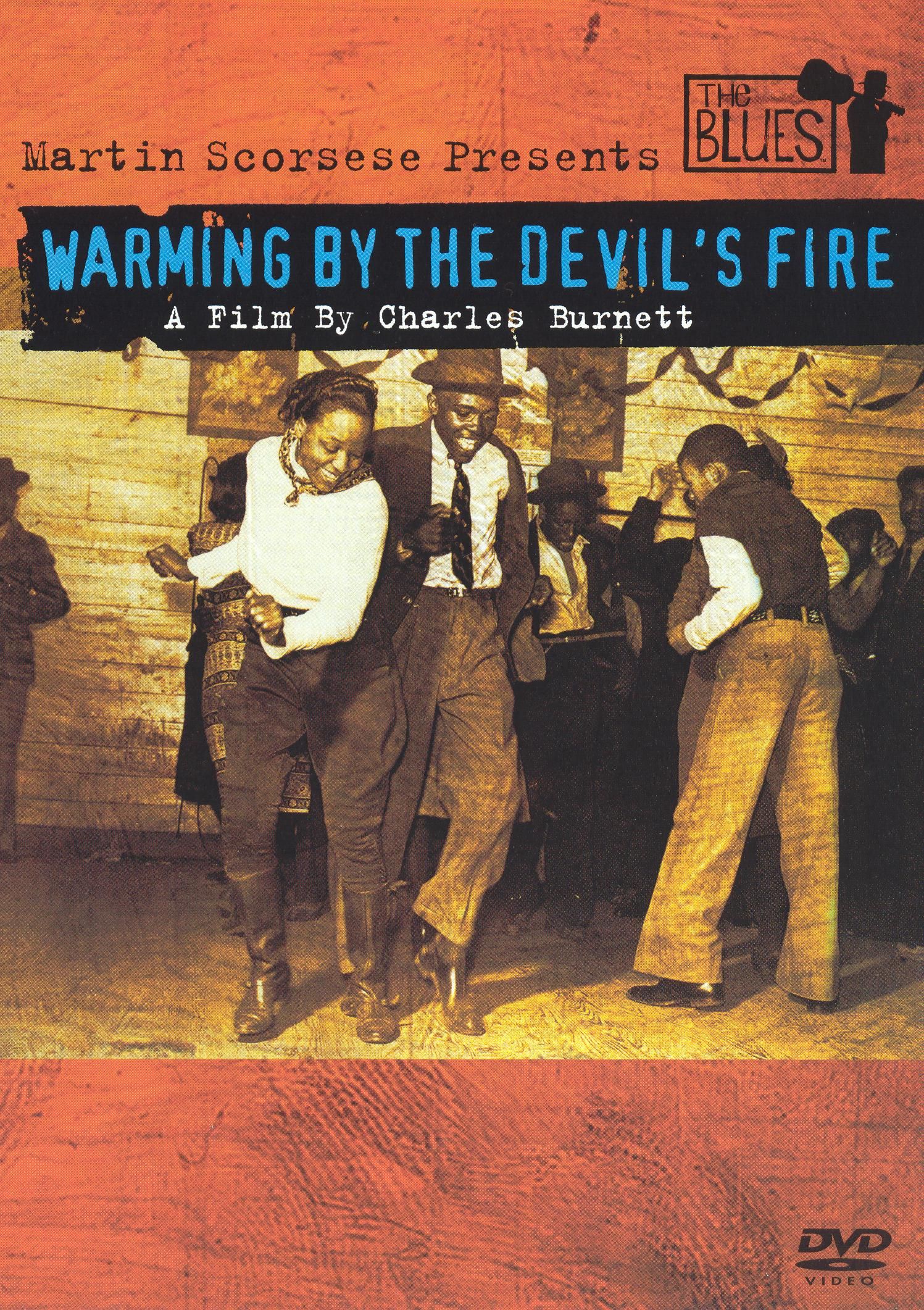

Charles Burnett’s Warming by the Devil’s Fire was the fourth in a series of seven PBS-TV films about blues music which were executive-produced by Martin Scorsese and directed by Burnett, Scorsese, Wim Wenders, Richard Pearce, Marc Levin, Mike Figgis, and Clint Eastwood. Burnett and Wenders took unorthodox approaches to the project by incorporating fictional elements into their films, but Burnett went further than Wenders, creating a fully developed fictional narrative interwoven with impressively selected archival footage. An early, extraordinary example of such footage is an archival clip of the black “Washboard Street Band,” composed of musicians playing washboard, a toy trumpet, and tin cans, and a small boy dancer in a derby who performs a sort of proto-break dance. There are also documentary images of hard labor and lynching.

Of all the directors involved, Burnett had the most intimate experience of the blues, and he wanted to make a film with a blues-like form, less about the technical aspects of the music than about the culture and feelings out of which it emerged. Warming by the Devil’s Fire is miles better than any of the other films in the series. As Bruce Jackson has said in a fine essay, the narrative structure is loose and episodic, “at heart it is lyrical, like the blues” (“On Charles Burnett’s Warming by the Devil’s Fire, www.counterpunch.org/2003/10/11). It’s also Burnett’s most autobiographical picture, mixing humor and history with the sad, sexual, sometimes raucous emotions of an old but still influential American art.

Burnett has often told the story of growing up in Watts to the sounds of his grandmother’s gospel records and his mother’s blues records. When he was a boy he sang spirituals in church and the first tune he played on his trumpet was W. C. Handy’s “St. Louis Blues.” It wasn’t until he reached adulthood that he realized how important both kinds of music had been, and they clearly influenced many of his films. At a deep level, he understood that the two musical forms were symptomatic of a conflict between the strictures of fundamentalist religion represented by his grandmother and the sadness, sex, and rebellion represented by his mother. This conflict is apparent in the very title of Warming by the Devil’s Fire, which suggests a guilty pleasure. At one point in the film we’re given the source of the title: we see old documentary footage of a southern black church service and hear the voice of a preacher admonishing his congregation to avoid their sinful pleasures, all of which, he says, are described in the 14th chapter of Luke as “warming by the devil’s fire.” (I asked Burnett where he found the recording of this sermon, and he couldn’t recall; my guess is that it’s a 1928 record by the Reverend Johnnie “Son of Thunder” Blakey.) As Burnett explained to interviewers, his film is an exploration of a partly forbidden art that had a complex impact on his upbringing: “I wanted to take more of a personal approach. I wanted to express my experience with the moral issues you might face growing up in a family that was divided on what is sin.”

Burnett’s grandmother and mother were the chief representatives of that division, but he also had two uncles who were opposites–a preacher in Mississippi who “believed in every word in the Bible” and an adventurous merchant seaman who “got along great” with his mother. The oppositions or dialectic within the family ultimately enabled him to see that spirituals and blues have a paradoxical relationship. “[I]f you really listen to the lyrics of some songs,” he has said, “you can see why [blues music] is not appropriate for children. There are images of low life, hard drinking. You had the church trying to get you up from the gutter and here you are singing [the gutter’s] praise.” At the same time, there were blues songs “that make a profound observation about life. They are lessons in life . . . case studies of people who loved and failed, of people who were wronged and who died in fights. . . . Blues has a survival component that gives you a better perspective of life at an early age than any first year of school, I believe. It teaches lessons. So do folk tales. . . . a lot of blues singers came from the church and a lot of blues singers towards the end of their lives went back to the church.”

Burnett’s interest in the blues was inseparably linked to his fascination with the South, where both his family’s religion and the blues originated. He was an infant when he and his parents left Vicksburg, Mississippi for California, but during the 1950s, when he was ten or eleven years old, his grandmother put him and his brother on a train from LA to Vicksburg so they could visit their southern relatives and make contact with old-time religion. In an interview presented as an “extra” on the DVD of Warming by the Devil’s Fire, he recalls that the train made a stop in New Orleans, where he and his brother had a traumatic encounter with southern-style segregation. At the station was a play room for white kids, and while waiting for a change of trains the two boys innocently wandered inside to look at the various toys. Suddenly everyone in the room exited and the place was surrounded by cops. The boys weren’t arrested, but they were shaken and extremely cautious when they finally arrived in Vicksburg.

Burnett’s memories of that visit had largely to do with the climate and unfamiliar aspects of southern poverty: stifling heat, humidity-laden air, and country out-houses that attracted rats and dirt-daubers (wasp-like insects that build ping-pong ball or even baseball-sized nests of mud). In his DVD commentary for Warming by the Devil’s Fire, he remarks, “When you’re a city boy it’s hard to go back to those things.” He understood why many of the people he knew, including his mother, never wanted to return to the South; but the history and music of the South continued to exert a mysterious, romantic attraction. In the eighties he returned to the area around Vicksburg to research a documentary that he never made, and during that visit he began to learn more about blues musicians.

Warming by the Devil’s Fire is inspired by Burnett’s visits to Vicksburg, but it also draws on his considerable knowledge of blues history. Set in the mid-1950s, it tells the story of an eleven-year-old boy named Junior (Nathaniel Lee, Jr.) whose family sends him by train to New Orleans, where, because his relatives don’t want him to ride a Jim-Crow train to Mississippi, he’s met by his Uncle Buddy (Tommy Redmond Hicks) and driven to Vicksburg in Buddy’s shiny Chevrolet. Buddy is a blues aficionado, but also a dapper rapscallion and ladies’ man who is disapproved of by the rest of the family; they openly wonder why he hasn’t been sent to prison, killed in a fight, or lynched. In the course of the film he takes charge of Junior’s visit, keeping him from the rest of the family and acquainting him with southern history and the lessons of life that blues music has to offer. All this is narrated off screen from the retrospective point of view of Junior as an adult (voiced by Carl Lumbly). Both of the principle actors in the story are charming and impressive, almost like a comedy duo: Nathaniel Lee, Jr. maintains a stone-faced expression, occasionally frowning in bewilderment but quietly absorbing the strange new world in which he finds himself; and Tommy Redmond Hicks talks non-stop, behaving like an exuberant force of nature who is passionate about the history of blues and fond of his nephew.

The fictional parts of Warming by the Devil’s Fire were photographed in color by John Dempster, who became Burnett’s most frequent DP, on locations in New Orleans, Vicksburg, and Gulfport, Mississippi. Burnett was disappointed by the fact that he was unable to shoot in high summer, but the film’s autumnal landscapes have a quiet beauty and are free of the cheap, gaudy, corporate chain stores that infest poor towns in today’s America. Most of the documentary footage of blues musicians is in black and white, and Burnett occasionally segues from that footage into fiction by printing the opening moments of the color fiction sequences in black and white. Near the beginning of the film, after a grim montage of old newsreels and photos of southern black labor and lynching of blacks, a color fade takes us from archival footage of blacks exiting a New Orleans train to a shot of Junior alone with his suitcase in front of the station. He’s neatly dressed in a 50s-style coat and tie, looking like a polite boy on his way to church. Buddy soon arrives, wearing a sporty cap and two-toned shoes. He gives Junior a warm welcome, ushers him into a sparkling, almost new Chevy, and takes him on a quick guided tour of New Orleans before they depart for Vicksburg.

First they stop on Basin Street, which Buddy explains was once the location of the Storyville red-light district, later immortalized in Louis Armstrong’s 1929 recording of “Basin Street Blues.” “In those days you didn’t need much money to have fun,” Buddy says. (Burnett cuts to old photographs and snippets of Armstrong’s music.) Then they stop at Congo Square, located inside what is now Louis Armstrong Park. As we can tell from Buddy’s enraptured speech, this is holy ground for anyone who regards blues and jazz as America’s truly indigenous art forms. Dating far back into colonial times, Congo Square was originally a place where enslaved blacks were allowed to congregate on their Sundays off—not for church, but for market, music, and dance from Africa and the Caribbean. It was closed before the Civil War but reopened afterward, when it became a gathering place for Creoles and a source of the brass-band rhythms still associated with New Orleans. (Burnett cuts to old footage of the Eureka Brass Band in a funeral parade through the nearby Treme district, playing “Just a Closer Walk with Thee.”) Its original name wasn’t officially restored until 2011, long after Buddy supposedly makes his speech and even after Burnett made the film, but lovers of blues have always known its importance.

The film proceeds by this method, allowing Buddy to teach Junior blues history and initiate him into an adult world, and giving Burnett the opportunity to show footage of musicians and the life that shaped them. One of the great virtues of Warming by the Devil’s Fire is that it says comparatively little about formal or technical aspects of the blues (which, at least on the surface, are relatively simple) and doesn’t try to define the term; instead it does something better, showing how musicians described the blues and giving a clear sense of the trials, tribulations, and profane pleasures that were its emotional sources.

The film isn’t simply an archive of great blues performances (though it is that) but also a meditation on black experience. It concentrates mainly on the harsh Delta blues that extended from Tennessee down to Mississippi and Louisiana, and without explicitly saying so it gives us subgenres of this music, all of them dealing with forms of trouble or desire. One kind has to do with the pains of sexual love. After playing “Death Letter Blues,” a song about a man who gets a letter announcing “The gal you love is dead,” Sun House (1902-1988) tells an interviewer that “Blues is not a plaything like people today think . . . Ain’t but one kind of blues, and that’s between male and female that’s in love . . . Sometimes that kind of blues will make you even kill one another. It goes here [slaps his chest over his heart].” But there’s another kind about the cruelty of the southern treatment of blacks. W. C. Handy (1873-1958) says that “When they speak of the blues . . . we must talk of Joe Turner.” Handy’s song about Turner (“They tell me Joe Turner’s come and gone, got my man and gone”) concerns a real-life character who lured Memphis black men into crap games and high-jacked them for deep-South chain gangs, where they provided free labor.

Some blues are quasi-work songs, such as Mississippi John Hurt’s “Spike Driver Blues,” which Burnett accompanies with powerful footage of black labor–men using steel bars as levers to rhythmically nudge an entire railroad track from one position to another; a row of five men in prison stripes standing close together and digging a trench by swinging pick axes in unison, the man in the middle flipping his axe in the air on the upswing and catching the handle for the downswing. Other blues are about weariness and soulful longing to be elsewhere. After playing “Nervous Blues,” bassist Willie Dixon (born in Vicksburg in 1915, died 1992) talks to his jazz quartet about the meaning of the blues: “Everybody have the blues . . . but everybody’s blues aren’t exactly the same. The blues is the truth. If it’s not the truth it’s not the blues. I remember down South, be on the plantation . . . and you would hear a guy get up early in the morning and unconsciously he’s [singing blues] about his condition and [wishing] he was some other place . . . down the road.” Still other blues, as with “Lonesome Road” by Lightnin’ Hopkins (1912-1982), are about a deep loneliness and wish to make contact with loved ones. We’re given an example of these feelings when Buddy drives Junior down the Natchez Trace (a location Burnett wasn’t able to photograph) and they pass an old man trudging down the empty road who turns down the offer of a ride. Buddy explains that the old man is lost in thought, making one of his long, periodic journeys from northern Mississippi to Parchment Prison to see his son, who for some reason never talks to him.

Parchment Prison was a source of blues music, as was Dockery Plantation, where blacks labored hard to pick cotton. Burnett shows documentary footage of the harvest at Dockery, and viewers of this footage can understand an observation Buddy makes when he takes Junior to Gulfport to view the Gulf of Mexico. Looking out at the vast, gray water and cloudy sky, Buddy seems relieved at the sight, just as Burnett’s seafaring uncle probably was: “You can’t pick damn cotton on the ocean,” he says. The film makes very clear how much the blues can be related to backbreaking work on the land or to long hours of menial domestic labor. Standing on ground near the Mississippi river, Buddy tells Junior about the 1927 Mississippi flood, the most destructive in US history; he doesn’t give statistics, but it left 27,000 square miles under water, in some places up to thirty feet, and displaced almost a quarter million African-Americans from the lower Delta. (Burnett’s grandmother, who experienced that flood, often talked about it.) We see documentary evidence of the devastation it wrought, and Buddy explains that black workers did a great deal of the labor needed to stem the floodtide. Archival scenes show black men in prison stripes trucked to work and trucked back in a windowless iron trailer with air-holes on its sides. With help from the Federal government, blacks also worked to construct the world’s largest system of levees along the river, but they got little reward.

Given this environment, it’s both understandable and amazing that nearly all the great blues musicians were self-taught. On the level of domestic labor, one of the most striking moments in the film, and one of the longest, is a documentary interview with the aged blues singer-guitarist Elisabeth Cotton (1895-1958), who, after singing “Freight Train” in a weak but beautiful voice, tells the story of how she acquired a guitar. When she was a very young woman, she went to white homes asking for domestic work. One lady invited her in and asked what she could do. Cotton proudly listed all her skills: cooking; setting a table; cleaning house; doing laundry; bringing firewood inside; bathing and looking after the lady’s children; etc. The lady hired her at seventy-five cents a month. After a year, the lady was so satisfied that she raised the pay to a dollar. Cotton gave the money to her mother, who months later bought her a guitar out of a Sears-Roebuck catalog. She smiles when she remembers that she couldn’t keep her hands off the instrument and almost drove her mother crazy learning to play it.

Charles Burnett’s interest in the blues was inseparably linked to his fascination with the South. In the 1950s, when he was ten years old, his grandmother put him and his brother on a train from LA to Vicksburg so they could visit their southern relatives and make contact with old-time religion.

Of course blues music wasn’t entirely about the woes of life. “With blues,” Buddy says to Junior, “you either laughed or cried.” A good deal of it, in fact, was about what the church called sin. We get a sense of this when Buddy takes Junior home with him to his tiny house, which looks like a blues museum. (In his commentary on the DVD, Burnett says that most of the old blues musicians, even the famous ones, lived in humble places like this, stacked with records and decorated with rare posters and photos; he also praises his production designer, Liba Daniels, for transforming an abandoned shack with very little money.) At night, Junior shares the narrow bed with Buddy, the two lying at opposite ends so that Junior’s head is at Buddy’s feet. Junior can’t sleep because when Buddy isn’t moving his toes to unheard music he suddenly jumps up and has a desire to put another record on the player. In the morning, Junior has his first experience of the horrors of the outhouse, made worse because the door won’t stay shut (there’s a blues poster on the inside of the door for convenient reading, and part of a broken 78rpm record on the wall). He finds a cat-gut string tacked to a post near the front door and strums it for a moment.

In the house, Buddy becomes Junior’s teacher. He shows the “cut and run” razor he keeps with him in case of trouble and begins playing records to exemplify the history of blues. This gives Burnett an opportunity to show archival footage of the people Buddy mentions. Buddy starts the day, as he does every day, by almost prayerfully listening to Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s “Precious Memories.” (Tharpe [1915-1973] was a singer of both blues and gospels; her rendition of “Precious Memories” was used for the opening of To Sleep with Anger). He then segues into a discussion of women artists, who were in great demand during the 1920s, before the recording industry began to dictate what could be heard. “So many women called themselves Smith,” Buddy says, among them Mamie Smith (1883-1946), the first woman to record blues, and of course Bessie Smith (1894-1937), featured in a clip Burnett shows us from the sixteen-minute film “St. Louis Blues” (1929). A montage of other female singers and songs features Ma Rainey’s “I Feel so Sad” (Rainey [1886-1939], the narrator tells us, was a successful stage performer who didn’t play juke joints and who worked with such musicians as Louis Armstrong; she was also a writer of songs with lesbian themes), “Four Day Creep” by Ida Cox (1896-1967), and a cover of “I Don’t Hurt Anymore” by Dinah Washington (1924-63). Buddy enthusiastically comments, “Those were some mean women, boy!” To reinforce his point, he plays a record by Lucille Bogan (1897-1948) and we hear a bit of the lyrics: “I got nipples on my titties big as my thumbs.” Suddenly realizing this might be inappropriate, he stops the record. The adult Junior’s narrating voice informs us that he decided to pretend he didn’t hear the words; Lucille Bogan, he says, had recordings that “would make the Marquis de Sade blush.” He adds that as a result of listening to blues, “I learned a lot about body parts.”

Buddy is obviously a man who loves women and makes no secret of the fact. Soon after playing the records, he visits a lady friend’s shot-gun house and introduces her to Junior. “This is Peaches,” he says, “one of the finest women God let walk on this earth.” He and Peaches cozy up and head off to the bedroom, backed by the music of Sonny Boy Williamson. (Williamson [1914-1948], the narrator explains, was the star of the “King Biscuit” radio show who was later killed in Chicago; we also see a clip of another, equally talented harmonica player [1912-1965] who somehow got away with appropriating Williamson’s full name.). Sullen, troubled, and beginning to disapprove of Buddy, Junior wanders outside. He gets in Buddy’s car and pretends to drive, then explores the neighborhood, coming upon a small church atop a hill. This discovery may seem implausibly symbolic, coming as it does on the heels of Junior’s increased uneasiness about Buddy’s sinfulness; but God and the Devil, like gospel and blues, are never far apart in this film, nor in back-country Mississippi. Junior goes into the empty church, which has a pulpit, pews, and a tapestry of the last supper (in his DVD commentary, Burnett says that the church was long abandoned and had to be fumigated for wasps before it could be decorated). Sitting on one of the pews, he experiences ghostly memories of churchgoing and seems to hear voices singing (“Things I used to do I don’t do any more”) and a preacher’s sermon, illustrated for us by old documentary footage.

When Junior and Buddy resume their drive, Junior pointedly asks about his other relatives in Vicksburg, whom he still hasn’t seen. Buddy ignores the question and resumes his lessons in blues history by commenting on the large number of singers who were blind, among them Blind Lemon Jefferson (1893-1929), Blind Blake (1896-1934), Blind Willie Johnson (1897-1945) and Ray Charles (1930-2004). But Junior looks unhappy. Sensing this, Buddy tries to cheer the boy up. “Let’s go see a movie!” he proposes. “Have you seen that movie Shane? I saw that one and High Noon about a dozen times!” Junior frowns and asks, “Why do you do bad things?” Buddy pauses, glances at him, and makes a prediction: “You’ll be surprised who you find in Heaven and who you find in Hell.”

Back at home, Buddy goes through a pile of old records and papers, including a yellowing, handwritten manuscript from a book he’s been writing about the history of blues. The book is unfinished because he still doesn’t have a beginning or end. The deep ancestry of the music, he explains, is in the early years of Reconstruction, in the era of Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Welles, and W. E. B. Dubois, when southern blacks had greater freedom of expression. By the early twentieth century, mass production made guitars available through mail order, and distinctive forms of blues developed in the southeastern states, the Mississippi delta, and east Texas. The first blues musician to publish his songs was W. C. Handy, who could be considered the godfather of such later figures as Mississippi John Hurt (1892-1966), T-Bone Walker (1910-1975), and Muddy Waters (1913-1983), all of whom we see in performance. The life of blues musicians, Buddy says to Junior, was often tough and self-destructive: Bessie Smith bled to death in an accident and Leadbelly and Sun House killed men.

As Junior’s education proceeds, he begins to form an imaginative attachment to the music and stories he’s heard. At one point we see him alone on a nearby dirt road, walking with his eyes closed, guiding himself with a long stick in order to experience what blindness must have been like for people like Blind Lemon Jefferson. Buddy takes him to visit a blind guitarist named Honey Boy (Tommy Tc Carter), who is sitting on his front porch with an aging, invalid gentleman named Mr. Goodwin. Buddy reverently explains that the invalid old man was once a player with The Red Tops (Vicksburg’s most popular blues, jazz, and dance band of the 1940s, which entertained both white and black audiences). Junior is amazed that Honey Boy knows he’s from California, and listens politely when the blind man tells him that blues musicians, if they live long enough, begin to mature and accept religion; he explains that he ruined his eyes and health from wild living and drinking too much home brew and “canned heat.”

Eventually, Junior becomes less concerned about Buddy’s womanizing. Buddy takes him for a fried catfish lunch at the home of two pretty young women who enjoy teasing him. Chucking Junior under the chin, one of them says he needs a better name and asks if he likes “Sweet Boy.” “No Mam,” he says, “I like Junior.” Broadly smiling and seductively looking him in the eyes, the other young woman tells him Junior isn’t “a name for a man.” She decides to call him “Sugar Stick.” Buddy plays a slow blues record and he and the awkward, shy, silent Junior begin to dance with the two women. Junior’s partner, who is much taller, buries his head between her generous breasts, whispering that when he gets older she’s going to teach him things. “I was backsliding into darkness,” the narrating voice of the adult Junior tells us. “I was between heaven and hell.”

Junior’s full absorption into the imaginative world of the blues happens when Buddy takes him for another drive, stopping the car at a country crossroads of the kind where Robert Johnson and other blues greats supposedly sold their souls to the devil in exchange for a devilish style. Buddy tells Junior that they’ll see the devil, but as night descends he falls asleep in the driver’s seat. Junior stares ahead into the mysterious, moonlit darkness, where the ghostly image of a well-dressed blues musician appears and speaks to him in the voice of W. C. Handy (who was still alive in the mid-1950s). Fearful, certain that he’s encountered an apparition of the devil, Junior shakes Buddy awake and tells him what he’s seen. Buddy explains he was only joking and explodes into waves of loud laughter. (In his DVD commentary, Burnett remarks that it was ironically difficult for the film crew to find a country crossroad near Vicksburg. He also says, “One would think this scene would be about Robert Johnson, but it’s not. It’s about this kid’s imagination.”)

Going deeper into the Devil’s territory, Buddy climaxes his course of study by taking Junior to a local juke joint crowded with drinkers and dancing couples. Junior gets a fish sandwich on white bread and sits at a table, where he eats and observes the action while Buddy perches in lordly fashion at the bar, turning toward the room and saying hello to the regulars. The woman who owns the place rebukes Buddy for bringing a kid inside, but he begs for just one beer and she relents. A sensible friend of Buddy’s steps forward, declines the offer of a drink, and tells Buddy he’s crossed a line by bringing a boy into the joint. Buddy laughs him off and the friend says “I give up,” exiting the place in disgust. Not long afterward a fight breaks out, viewed from over Junior’s shoulder, and a man across the room is knocked to the floor. The owner and her bouncers put the unconscious man in a chair and relieve him of a switchblade. Buddy leans toward Junior and asks, “Having fun?”

Just then the disgusted fellow who walked out returns with Buddy’s brother—he’s Uncle Flem, Junior’s opposite, a preacher dressed respectably in a suit. Flem tells Buddy that Junior’s family in LA and relatives in Vicksburg have been worried to death, and that Buddy is “crazy.” Buddy knows that his time with Junior is up. He moves to the boy, gives him an intense look in the eyes, and hugs him. Flem announces that he’s taking Junior to the decent members of the family elsewhere in Vicksburg. As Junior is led away, he looks back at Buddy. Burnett freezes the frame for a moment, holding on the boy’s gaze, and then shows him leaving.

This is the end of Junior’s association with Buddy, but not the end of Buddy’s influence. As the film closes, Junior’s narrating voice tells us “I learned so much on that trip back home. I never forgot a second of it. I draw a lot from that time I spent with Buddy. . . .The years went by, and Buddy left the book for me to finish. I did, in my own way.” We see a still photo of Buddy in a suit, next to Flem, holding a Bible to his heart. Junior’s voice says, “Buddy ended up becoming a preacher, like so many of the blues players.” Viewers might conclude that in his “own way” Burnett himself finished Buddy’s book, paying full tribute to the things he learned by visiting his birthplace.