Nelson Lyon’s The Telephone Book comes to the IU Cinema ◆ by Russell Sheaffer

[The Underground Film Series will screen the 1972 film, The Telephone Book, at the IU Cinema on October 4 at 6:30pm.]In 1982, John Belushi went on a drug binge that ended in his untimely death; Saturday Night Live writer Nelson Lyon was there and it destroyed his career. Lyon, who wrote for Saturday Night Live between 1981 and 1982, had a sordid relationship with the film industry after Belushi’s death. For most people, the simple connection between Belushi and Lyon made up the extent of their knowledge about the latter, he had trouble finding work, and his filmography remained thin. In fact, Lyon’s only feature-length directorial effort, a sex romp titled The Telephone Book (1972), seemed to be facing a demise similar to his own; it had been forgotten amongst the many other films and filmmakers who made work in the flourishing New York City film scene of the 1960s and 70s. With the recent restoration of The Telephone Book, however, Lyon’s little-known gem has attracted a new-found cult following, giving fans and scholars alike the chance to reevaluate Lyon’s life and work.

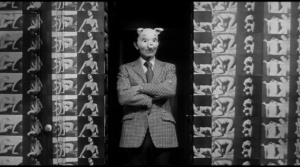

Norman Rose in “The Telephone Book”

■

In 2012, Nelson Lyon passed away at the age of 73 years old. He’d had a fascinating life, but his filmography was short and his once promising career as a filmmaker had proved less than glorious. Lyon had been living and working in New York City during the flourishing underground film scene of the 1970s, he’d been a part of Andy Warhol’s art studio called The Factory, but his name never found a home amongst the greats. He had a brief moment of critical success with The Telephone Book in the 1970s but, after his stint writing for SNL, he ended up making trailers for other people’s movies and nothing quite compared to his short, albeit disastrous, time in the spotlight.

When it was released in 1972, The Telephone Book screened theatrically in New York and Los Angeles and was deemed a “bleakly brilliant” film for “sophisticated adults” by the Los Angeles Times and “one of the freakiest, funny, dirty movies ever made” by its own promotional posters. Produced by Merv Bloch, the film was paid for with money Bloch had made designing promotional materials for films like 2001: A Space Odyssey and, as its advertising suggests, The Telephone Book is unlike anything you’ve ever seen. On a surface level, the film is a wonderfully entertaining adventure that follows a young woman, Alice, as she searches the streets of New York City trying to find “John Smith,” a man that she’s fallen in love with over the telephone. John, her telephone-lover, spends most of his time making obscene telephone calls to housewives, grandmothers, and adolescents all over New York City and he has made quite a name for himself.

On her quest to find “John Smith,” Alice runs into an onslaught of various sex-obsessed characters from a stag filmmaker planning his comeback to a deranged housewife to two regulars of Andy Warhol’s Factory, Ultra Violet and Ondine. This array of porno character types and pop culture icons keeps the film moving along at a ludicrously quick and delightful pace, climaxing with an animated sequence that is nearly impossible to describe. Shot in high contrast black and white, The Telephone Book is in a category all its own, simultaneously a critique, a satire, and a part of the explosion of theatrical pornography that swept the country in the 1970s.

Sarah Kennedy In “The Telephone Book”

■

In 2010, just two years before Nelson Lyon passed away, The Telephone Book was rediscovered and began a revival tour that has taken it around the country, playing to audiences who had never heard of the film, much less Nelson Lyon. In retrospect, the film has been called “a brilliant and lamentably neglected gem of early-’70s underground filmmaking” by Slant Magazine and The Chicago Reader’s Ben Sachs noted that The Telephone Book “conveys a youthful enthusiasm and a curiosity about what can be done with film comedy,” a sentiment that I agree with whole-heartedly. Thanks to the film’s newfound cult status, we’re presented with a promising, young filmmaker whose dreams were crushed too quickly and whose work was pushed aside amidst a series of phenomenally unfortunate circumstances. Retroactively, we are finally able to recognize Nelson Lyon for what he was: a talented, culturally savvy voice that was able to provide biting critique of a system while simultaneously being a part of it.

The Telephone Book is rated X and, as such, IDs will be required and no one under the age of 18 will be admitted. The screening is free, but ticketed. More ticketing information.

Other upcoming programs in the Underground Film Series include a night of shorts titled “Exploding Lineage: Queer of Color Histories in Experimental Media,” co-presented with the Black Film Center/Archive on October 11 at 6:30pm, a family-friendly program of Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion animated fairy tales on October 19 at 3pm, and a not-to-be-missed program of west coast underground short films from the likes of Kenneth Anger, Maya Deren, James Broughton, Barbara Hammer, and James Franco on October 25 at 7pm.

The Ryder ◆ September 2013