Small moments of personal revelation, big emotional cues, and a laundry list of indie quirks ● by Jonathan Knipp

Before I explain my collection of highlights from the 2014 year in movies, I have to unpack my standard disclaimer: my year’s screening adventures are still unfinished. I haven’t even decided in what format I’ll see Interstellar. And that leaves a prestige pile-up on the horizon: The Theory of Everything, The Imitation Game, Whiplash and many, many other titles filling up critics’ top 10s have yet to make it to my local art house, multiplex or On-Demand channels. But the titles I’ve selected for discussion, while perhaps not conventional best-of-the-year material, represent a cinema that continues to confound and fascinate as Hollywood unloads its award bait at year’s end.

Under the Skin

The ambiguous first images of Under the Skin suggest the assembling of an artificial eye, a manufactured point of identification for the audience with the film’s main character. As detailed and micro-managed as this attempt to unite the viewer with Scarlett Johansson’s pro/antagonist appears, the film remains elusive, unmooring, unsettled. Director Jonathan Glazer’s approach careens from long shot/take observational quasi-documentary to cryptic, murky art film: The Man Who Fell to Earth with moments of genuine, found-footage authenticity. By its end, Under the Skin’s principle character has emerged as abject, alien horror and sympathetic final-girl while stalking through the year’s richest, most deeply textured visual experience.

Transformers: Age of Extinction

Obscurity and irrationality weren’t consigned exclusively to the art house this year, as Michael Bay’s exhilarating/repulsive Transformers: Age of Extinction brought nothing less than the collapse of reason to the multiplex. The film is positively hallucinatory in it intensified visual strategies; a huge-budgeted, corporate-logo-smothered, strobing installation piece. It is also, unlike most of the reviews I read, an arrestingly off-kilter piece of tent-pole franchising. Bay is a frequently brilliant practitioner of intersecting action planes, dynamic framing, expansive location use and eye-melting color. He is also (be warned) a seasoned vulgarian, so bring some pearls to clutch. More traditional summer spectacles proved that Hollywood could still mount large-scale, gimmicky sci-fi star vehicles with humor, sex appeal and narrative momentum, such as Edge of Tomorrow, and splashy, franchise-adjacent, big-budget comic book ensembles with unexpected heart and poetry, like Guardians of the Galaxy.

Boyhood

Richard Linklater’s Boyhood seemed pre-ordained for year-end consideration by virtue of its unprecedented formal experiment: shooting its principle character’s physical/emotional/political maturation over the course of 12 years. Mercifully, or perhaps characteristic of the director, the film contains mostly small moments of personal revelation while larger dramas brew along the margins of the screen. The result is a singular cinematic experience. Most importantly, the film allows the viewer access to categories beyond what its title suggests, with profound, memorable parallel narratives happening throughout the main character’s Texas home.

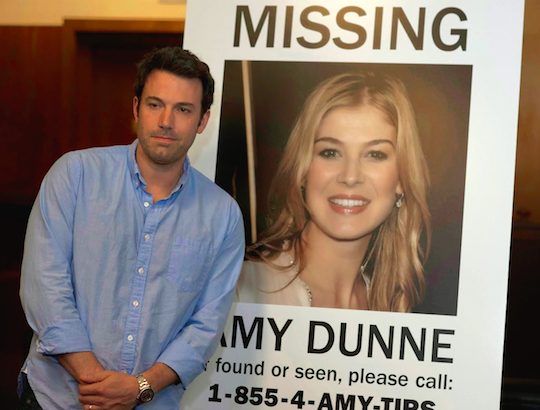

Gone Girl & Nightcrawler

Occasionally, a film will address itself in a manner that is surprising and purposeful. Both David Fincher’s adaptation of Gone Girl and Dan Gilroy’s directorial debut Nightcrawler transcend their respective conventions, the rabbit-hole mystery of a domestic crime thriller and the psychological profiling of a Taxi Driver-esque character study, to become meta-studies of something larger. In Fincher’s film, the twisty plot structure asserts that suburban neighborhoods are filled with women whose narratives have been forced upon them and illustrates the violent repercussions of one woman’s attempt to forge her own.

Gone Girl

●

Nightcrawler’s writer-director Dan Gilroy does something even more surprising: once the film issues its expected media critique, the film becomes an impassioned argument for visual literacy in the face of media over-saturation. Not content to simply issue another hand-wringing indictment of local news sensationalism, Nightcrawler becomes a dissection of video demagoguery.

Step Up: All In

The Step Up franchise burned itself out this summer without anyone really noticing. It’s a sad passing in a way, since few contemporary franchises celebrate cinema’s elemental qualities with such style and energy. Perhaps the series produced only one unqualified masterpiece: Step Up 3D, a sensational collection of numbers that transforms, miraculously, into a blissful catharsis of color, sound and movement (dynamically directed by John M. Chu). Step Up: All In comes close, though. With latter day music video wiz Trish Sie directing, the film once again seizes the opportunities offered by 3D projection and ups the ante, playfully contributing gags based on scale and perspective along with numbers of staggering, superhuman momentum. But, as one of my wife’s colleagues noticed, where can a dance franchise go when the object is to land a steady gig with insurance benefits? The country’s economic transformation, it seems, leaves unanticipated casualties everywhere.

Obvious Child

The “Star Vehicle” could be another cinematic event diminished by hard times. Still, a few films this year reminded me of the richly empathic possibilities of a charismatic lead performance. Obvious Child is, for the most part, a glorified stand up set with a laundry list indie-quirk tics that should disqualify it from consideration. The comedy club scenes are padded with extended moments of comic banter. Supporting characters appear drawn from the same collection of tired spare parts: sad, self-deprecatingly gay club MC; whimsical puppeteer dad and brittle, academic mom; David Cross. But at the center is a figure so empathetic that the clichés either work in her favor or fall to the wayside. Jenny Slate, as a floundering NYC comic who finds herself unexpectedly pregnant, elicits a profound connection almost absent mindedly, even as the film introduces us to her deep, expansive support network. The filmmakers may have wanted to downplay (slightly) the film’s abortion theme, but in depicting a shadow community of women sharing a personal experience like a secret language, the film becomes the best possible kind of pro-choice advocacy.

John Wick

John Wick, on its slick surface, seems to fall squarely in the “pro-death” camp. But this exercise in style has at its center a performance by Keanu Reeves that practically vibrates from the frame outward. This is broad-stroke genre filmmaking of the highest order, with big emotional cues (the inciting incident is a puppy’s murder!), dirty double crosses and sadistic villainy. Reeves’ very specific screen presence keeps the whole affair surprisingly human through all its clockwork flourishes. Ultimately, John Wick offers a better argument for the gun fight as a cinematic event than the growing mountain of ‘80s action star comeback vehicles.

The Babadook

[The image at the top of this post is from The Babadook.]

And finally there’s the curious case of The Babadook. Jennifer Kent’s first film, an imaginative horror film, concerns a storybook monster’s possible emergence into a young widow and mother’s home. But at the heart of the film is a tense, fraught relationship between a mother and her son. Surprisingly, the film doesn’t stack the deck against either participant: the mother isn’t neglectful; the boy can’t be construed as monster or nascent psycho. And at this intersection of approachable realism and fanciful horror the film generates deep, resonant terror. In its way, the film provides a powerful bookend to Boyhood with all its fears and hopes for the future tied to an inscrutable childhood.

Jon Knipp lived in Bloomington and wrote about film in The Ryder in the late 80s and early 90s. It’s good to have him back.

The Ryder ● January 2015

The Babadook

Gone Girl