▼

A Family Re-enchantment ◆ by Shayne Laughter

This story from the Papaw Project collection, “The Stronger,” was published in the Spring 2011 Bacopa Literary Review. Shayne will read “The Last” — based on her great grandfather’s encounter with a mystery on the Kansas prairie — at 1:30 pm, Saturday, August 31, at the 2013 Fourth Street Festival’s Spoken Word Stage.

◆

It was a classic setup. In 2007, I moved back to Bloomington from Seattle to get Mom through knee replacement surgery. “Would you please go through this trunk,” she said, “and throw out some of Papaw’s papers?” A classic setup, and a classic payoff. Granddaughter meets Grandfather’s writings in a file folder stashed away in a trunk.

My Papaw died in 1976, age 81. An autopsy showed that he had been enduring Alzheimer’s, which explained the bad temper of his last years. Elmer Guy Smith had been born in Tipton County in 1895, the late baby of four children. He had two years of military service in Paris and fifteen years as a Veterans Administration payroll accountant in Washington, DC, but lived most of his life in Bloomington and Monroe County.

Elmer Smith had more poetry in his nature than was entirely helpful to a farming family teetering on the edge of poverty. His parents had come north from Kentucky to work more fruitful land in Indiana. After a few years in Tipton County, they wound up south of Bloomington on South Rogers Street, on acreage bordering the Monon track between Indianapolis and Louisville.

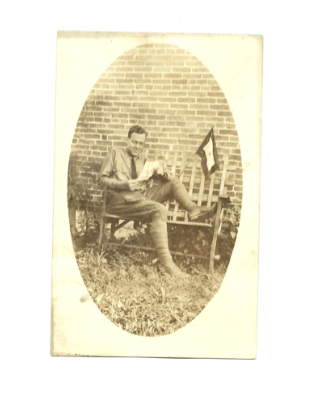

Elmer Guy Smith, 1920

■

The farm house was built in 1848 and burned in the 1930s, after Elmer finally sold the place. Elmer called it Glen Echo Farm. He wrote in a 1976 letter (all quote marks are his):

I have never “set foot on the 28 hopeless acres” since 1924. Highway #37 came later, but when I sold, it was very inaccessible – across two railroads and the creek that often flooded, carry (sic) raw sewage from the “city plant” and creosote from the plant ¼ mile north. In dry weather the R. R. engines set fire to the pasture grass, and I would have to run down the hill, & grab the bucket of water and jute-sack I kept there, to try and beat out the fire, before it ruined the pasture-land.

(The creek he mentions is Clear Creek, and the creosote plant was still in operation at the south end of the Monon [now CSX] Switchyard, during my childhood in the 1960s.)

At Bloomington High School, Elmer won honors for his poetry and essays. He graduated and went off to the Great War in 1918, came down with the Spanish Flu and shipped to an infirmary in a chateau the minute he set foot in France. He had trained as a machine gunner; the flu was probably what saved his life. Few of his unit survived battle.

Being six feet tall, Elmer was reassigned to Military Police once he had recovered his health. His post was Gare Montparnasse in Paris, after Armistice and during the peace talks at Versailles. Elmer kept a diary and asked his family to keep the letters he sent home; he had an idea he wanted to be a writer.

From the same 1976 letter: From that house one could hear the “echo down the valley” as the trains went a-whistlin’ south-bound. From there I went “down the valley” on the “troop-train” with a lot of other Monroe County boys, in 1918.

In the early 1930s, his wartime letters and diary entries were published as weekly columns in the Bloomington Evening World (he took his five-year-old daughter with him to deliver them, and she got bit by the newspaper bug). He carefully clipped the columns and glued them into the pages of blank books he paid to have printed with the column’s title on the cover and spine: Away From Glen Echo. It was a poor man’s vanity publication; just three copies were made.

Then, when Elmer was forty years old — husband and father of two, eking out a living as a Library Assistant at IU under the WPA — he was finally able to take college courses, thanks to Depression-era schemes for WPA workers and War veterans. Accounting turned out to be a breadwinner, but English Composition was where his heart had been aiming since boyhood. In these classes he was finally able to play with his memories and family tales, to shape them and see what could come up from under his pen.

By the time Elmer died, I was already familiar with Away From Glen Echo. I didn’t like my grandfather’s writing at all. He was sentimental and used far too many “quote marks.” I felt deeply embarrassed for him.

Yet when I read through the little class assignments, something was different. He wasn’t giving an account; he was using bits of his memories to tell a story. He still wasn’t terribly good, but he had a knack for descriptions of country life. That knack beamed like a sweeping radar arm, showing me where jewels lay buried. I knew I could reach them, with fiction.

Four years later, I have finished three stories of a four-story collection based on these writings. Does that mean the stories are now mine? Or are they still his? Papaw did plenty of fictionalizing himself, since he obviously changed place and character names to mask his loved ones and his home.

My mother – now eighty-six and a long-retired newspaper editor — isn’t sure she agrees with my enthusiasm for fictionalizing her father’s life. I’m okay with that. For me, this “Papaw Project” isn’t about reporting what happened. It’s about fiction’s re-enchantment of a hard country life – and the jewels Elmer could not quite reach.

◆