▼

◆ by Laura Ivins-Hulley

[

The Burroughs Century, a five-day festival at Indiana University and in local venues, will take place February 5-9, celebrating what would have been Burroughs 100th birthday and featuring events devoted to the author’s written and visual artworks, his life, and his legacy. There will be a film series, art and literature exhibits as well as a display of Burroughs’ shotgun paintings, speakers and panels, musical performances, and more.]

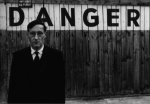

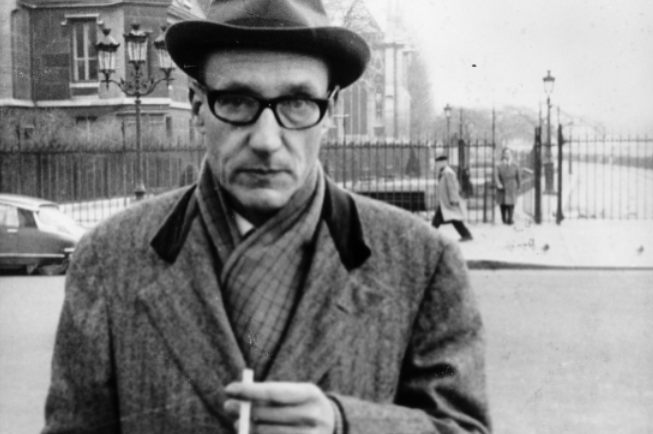

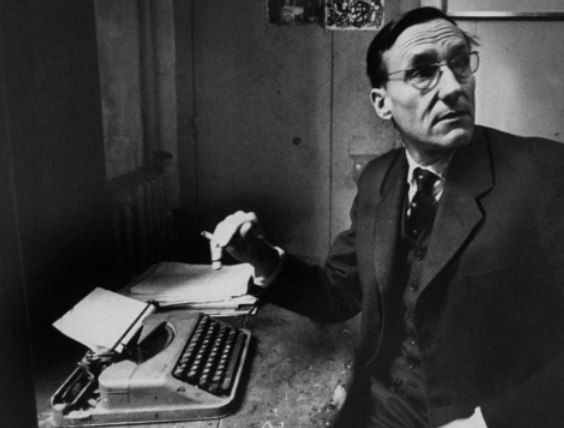

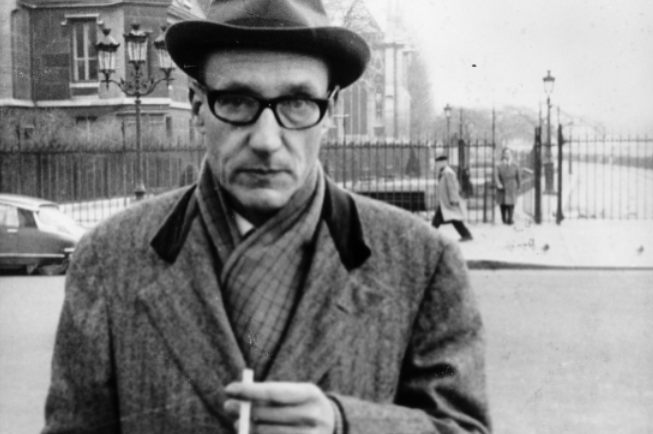

Though slight of build, William S. Burroughs was no gentle soul. His life and writings are marked by a certain violence. Not the violence of those literary adventurers — though Burroughs certainly had adventures — who went to war and ran with bulls and reveled in masculinity, but a violence nonetheless. Fascinated with guns and possessing a morbid streak from an early age, Burroughs’ life had many close calls and a few formative tragedies, something reflected in the form and content of his novels.

A member of the Beat generation of writers, Burroughs’ impact on 20th century art and literature is far reaching. He helped inspire cyberpunk literature, and such musicians as Roger Waters and Kurt Cobain have cited him as a primary influence. In 1992, while in his late-70s, Burroughs collaborated with Kurt Cobain to create an album called The ‘Priest,’ They Called Him, a mixture of Burroughs spoken-word art and Cobain’s music. In 1989, he appeared an aging addict in Gus Van Sant’s Drugstore Cowboy, and in 1991, David Cronenberg adapted Burroughs most well-known novel, Naked Lunch, for the big screen.

Notwithstanding his longstanding influence as a counterculture figure, William Burroughs was born to rather innocuous circumstances, on February 9, 1914. His grandfather invented an adding machine for banking, and a century ago, one would associate the Burroughs name with the Burroughs Adding Machine Company, which remained a key computing company well into the 20th century. His parents were well-to-do inhabitants of St. Louis, and the young Burroughs grew up with a maid and a nanny.

■

Burroughs never quite fit into the respectable life of the bourgeoisie, which many of his classmates and neighbors inevitably noticed. He looked, they thought, “like a sheep-killing dog” or “a walking corpse” and one of his schoolmates considered him “a character” of “the wrong kind.” Fooling around with a chemistry set at the age of 14, the young Burroughs nearly blew off his hand. He received morphine for the surgery and spent six weeks in the hospital, but luckily did not lose the limb. This would be his first close call, and the trauma coincided with his first experience with morphine, a drug that would come to dominate his life three decades later.

Around this same time, Burroughs discovered a memoir, You Can’t Win, by a cultural outsider with the pen name Jack Black. Black was a high school dropout, an addict, and a crook; he was just the sort of hero Burroughs didn’t know he was looking for. The book contained colorful characters like “Salt Chunk Mary,” who dealt in stolen goods, and detailed a world of criminality that was foreign to the adolescent Burroughs. You Can’t Win remained a touchstone for the author into adulthood, and after several years of living his own outsider lifestyle, Burroughs modeled his confessional first-published novel, Junkie, after Black’s memoir.

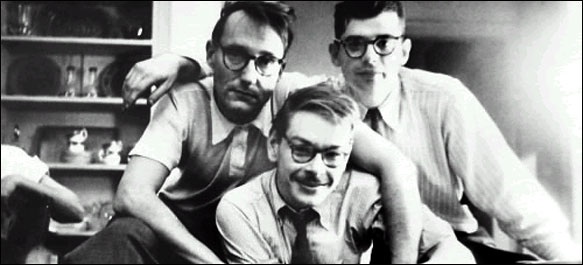

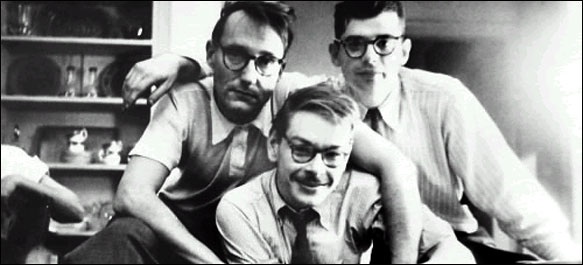

Despite this early inspiration and a few interesting pieces written in his youth, Burroughs did not become a “writer” until almost 40. And moreover, he was older than his Beat generation comrades, Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. By the time the trio met, Burroughs had traveled through Europe, explored a never-realized career in psychoanalysis, and plunged himself into an ill-fated affair with a hustler named Jack Anderson, a relationship that ended with Burroughs cutting off the tip of his finger in a bitter, Van Gogh-ian gesture. When he met Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg in 1944, he was 29, Kerouac nearly 22, and Ginsberg 17. Well-educated and with a self-possessed demeanor, Burroughs quickly became a mentor to these two young writers, though it had been several years since Burroughs had written anything himself.

Later that year, though, Burroughs did pick up the pen again, but the circumstance that led to him writing represents one of the formative tragedies in his life. In August 1944, two good friends of his got into a drunken argument by the Hudson River, and one (a man by the name of Lucien Carr) stabbed the other to death. Carr immediately sought out Burroughs, who told him, “Get a good lawyer,” and “make a case for self-defense.” Carr then went to see Kerouac, who helped him get rid of the dead man’s glasses and the murder weapon. After Carr turned himself in, the police arrested Burroughs and Kerouac, though both were promptly bailed out, Burroughs by his parents and Kerouac by his girlfriend. The murder shook up the three friends, and they each attempted to write about the event, with Burroughs and Kerouac collaborating on a novel they never managed to publish in their lifetimes.

Burroughs (l), Lucien Carr (c) & Allen Ginsberg

■

Still, though Burroughs was doing some writing, he was not yet “a writer.” He had to undergo more hard living and an almost overwhelming tragedy before he would earnestly begin his writing career.

Enter Joan Vollmer.

Like Burroughs, Vollmer hailed from a well-to-do family, but rejected following her parents into a bourgeois life. She was intelligent, attractive, and sexually free, and although Burroughs had long expressed a sexual preference for men, the pair developed a personal intimacy that led them to become common-law spouses. Their relationship continued between poles of intimacy and frustration. A friend once commented on their telepathic connection, and their devotion to each other — as they traveled from New York to Texas to Mexico, on some scheme or escaping failed schemes — was clear. Still, Burroughs maintained more sexual interest in men than in his wife, and both were addicts. Burroughs alternated between opiates and alcohol, while Vollmer preferred Benzedrine and later turned to tequila while in Mexico. Vollmer was often left frustrated, but the pair did manage to conceive a child, William S. Burroughs III.

While living in Mexico, Vollmer’s health deteriorated, and their relationship grew volatile. However, no one could guess how things would actually end. During a night of heavy drinking with some friends, Burroughs joked, “I guess it’s about time for our William Tell act.” Unbelievably to the others in the group, Vollmer put a glass on her head, laughing somewhat as she did it, and then Burroughs took aim at the glass and shot. The glass fell, unharmed. The shot through Vollmer’s head was fatal.

Through some shady legal wrangling, Vollmer’s death was ruled an accident, and Burroughs ultimately spent only 13 days in jail. The event, however, haunted him throughout his life, forcing him to write as a means to chase sanity. “I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would never have become a writer but for Joan’s death,” he once claimed. “So the death of Joan brought me in contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and maneuvered me into a lifelong struggle, in which I have no choice except to write my way out.” Burroughs son and Vollmer’s daughter from a previous relationship went to live with grandparents, and Burroughs began a series of adventures in South America, hunting for a drug called yage which had purported mystical properties.

■

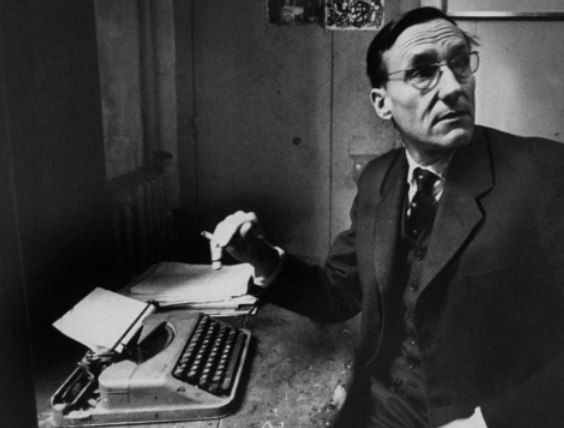

In 1953, a dime-back press published Burroughs novel, Junkie, the cover marketing it as a pulp confessional. The book proved a relative success — selling over 100,000 copies — but Burroughs was still in South America looking for yage and seemed not to care. Like his childhood inspiration, You Can’t Win, Junkie plunges into an underworld of drugs and criminality and was culled from many of Burroughs’ own life experiences. Written in a matter-of-fact style, the novel contains explicit descriptions of drug use and the culture of addiction, but moments of philosophical candor pervade the text. It is not simply a dime-back confessional, but a vivid meditation on the meanings of addiction.

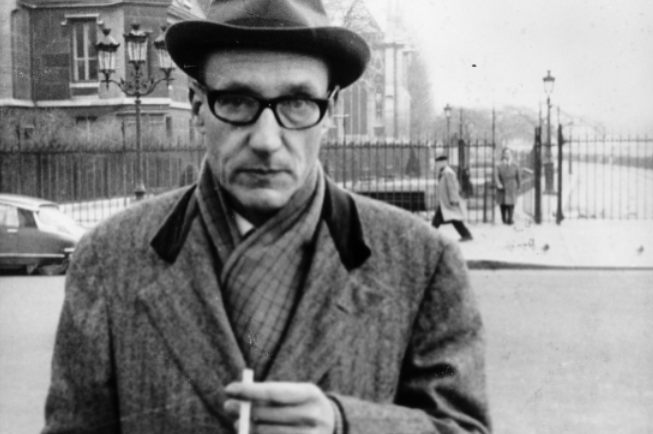

Returning to New York from South America, Burroughs attempted to kindle a relationship with Ginsberg, but his friend rebuffed his advances. So, rejected and tormented, Burroughs path eventually led him to Tangier, Morocco, where he continued his junk habit and wrote the bulk of his most famous novel, Naked Lunch.

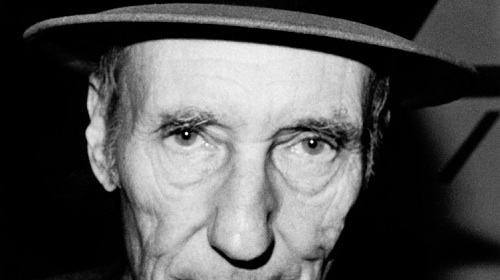

The years spent in northern Morocco proved a dark, lonely period in Burroughs’ life. He had difficulty in getting over his affection for Ginsberg, his addiction intensified, and his physical appearance assumed a ghostly character. He wrote compulsively, but could not manage to organize his many pages of script, and though his friend had rejected him, letters to Ginsberg served as a lifeline during this period.

In 1955, at the age of 41, Burroughs had hit an emotional wall. Alienated from his friends both geographically and emotionally, he lived a hollow cycle of need sated briefly by needles. Later, he would remark, “I suddenly realized I was not doing anything. I was dying.” At this point he made a decision. He was determined to quit junk.

Of course, Burroughs had made this decision before, quite unsuccessfully. Somehow, though, now it worked. With renewed vigor, Burroughs returned to his writing, experiencing a level of productivity that was completely new to him. Soon, Kerouac, Ginsberg and Ginsberg’s boyfriend, Peter Orlovsky, traveled to Tangier to visit Burroughs, marking an end to that tormented chapter of Burroughs’ life. Ginsberg and another mutual friend spent a few months helping Burroughs edit Naked Lunch, and the novel was published in 1959.

Violent, relentless, and lacking any coherent linearity, Naked Lunch was a revelation. As with Junkie, the author drew from his own life while writing, but it cannot be characterized as autobiographical. The story moves promiscuously through different times and settings, with mysterious agents and explicit sex and, of course, frank descriptions of drug use. The purposefully obscene content prompted multiple bannings of the book, as well as an obscenity trial in Boston. Considering Naked Lunch a great literary accomplishment, Norman Mailer testified in Boston on the novel’s behalf. At one point he told the court, “There is a sense in Naked Lunch of the destruction of soul, which is more intense than any I have encountered in any other modern novel.” Mailer’s observation assumes an additional air of truth when we think about Burroughs tormented existence through much of Naked Lunch’s writing.

In Naked Lunch, we can see Burroughs marrying violence of content to violence of form, but it was not until he discovered the “cut-up” method that this impulse was fully realized. A form of verbal collage, the cut-up method involves literally slicing up pages of text with a pair of scissors, and rearranging those pieces to create unexpected juxtapositions. Not everyone in the literary community appreciated such a method (Samuel Beckett once referred to it as “plumbing”), but through it Burroughs produced a fascinating set of novels called The Nova Trilogy.

The three editions of The Nova Trilogy — The Soft Machine, The Ticket That Exploded, and Nova Express — contain pieces drawn from multiple sources. Readers familiar with Naked Lunch will recognize its presence in the trilogy, and it also contains scraps from Shakespeare and T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. The novels possess a similarly explicit content as Burroughs’ previous works, but the cut-up method leads to text that is more fragmented and yet more rhythmic than Naked Lunch. Phrases recur like a refrain in poetry, but it is not always clear how they relate to the scenes surrounding them. Partially inspired by surrealist methods for creating art, the novels lead readers to explore their own associations, making it impossible to pin down definitive meanings for the disjointed imagery.

■

Though Burroughs’ career as a writer began later than his peers, his influence is wide-reaching. Ultimately, despite being several years older than both Kerouac and Ginsberg, he outlived them both, dying at the age of 83 four months after Ginsberg. Now, in the 21st century, Burroughs continues to be a touchstone for a new generation of writers and artists who seek to push the limits of language and adventurous living.

The Ryder ◆ January 2014