A Memoir as Historical Fiction

by John Bob Slone

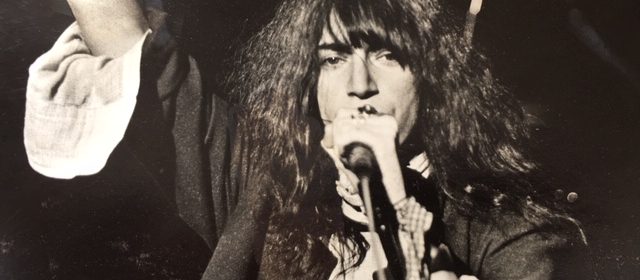

I was thinking recently about the time I met punk-rock’s

poetic high priestess, Patti Smith. It was 1976; she and her band were touring

behind their newly-released Horses

album. One of the tour venues was the Poplars Hotel Ballroom in Bloomington.

That in itself was newsworthy. The Poplars was owned by Indiana University and,

by reputation, represented all that was staid and conservative in the Midwest.

The hotel had never before hosted a concert, let alone a band of wild, grungy,

high-volume, NYC punk rockers. It was, to put it mildly, a curious

juxtaposition. But what was even more curious was this odd match made for a

happy marriage.

It was a strange brew, but a delightfully delicious one, a

blend so special blend that it etches an extra-deep groove in the record of

memory. From such a deep groove, memories are manifest in high-def full color

with a quadrophonic soundtrack; the sights, sounds, touches and smells remain forever

fresh. In short, they are memories that can be relived. So cue up the swirling

harp music and follow me back in time to the day I met Patti at the Poplars.

~

I’m a 24-year-old freelance journalist, and I’ve been asked

to cover the show for Primo Times, a

regional alternative weekly tabloid. It’s a peachy assignment. Primo circulates 100,000 copies with

editions in Bloomington, Lafayette, Indianapolis and Terre Haute. Printed on

thrifty newsprint, the mag is distributed free of charge and is one of the most

widely-read publications in Indiana. Every Friday they leave big stacks of

their colorful papers around Bloomington. By Saturday, they are gone.

I love working for Primo.

Part of that affinity lies in numbers. I like the large numbers of readers, and

I like the large numbers on their checks. But numbers aside, what I like best

about Primo is their managing editor,

Vic Bracht. He lets me write whatever I want and makes sure my stuff is only

proofread and never edited–unless for space :(. To me, he is the perfect

editor, and he stands barely a notch below Buddha in the echelon of my esteem.

It’s a given that Vic steered this much-desired story my way.

Editorially, Primo

Times is much more culturally than politically inclined. The philosophy is,

since no news is good news, traditional news should be avoided in most cases.

That makes this story, Patti Smith coming to Bloomington, a candidate for Primo’s biggest story of the year. Patti

is more than just making waves. She is the

wave. And now she’s making airwaves with Horses,

and I can hardly wait to ride them.

Even before this tour, Patti was long legendary in punk

circles. She was a regular at CBGB, New York’s punk Mecca. From there her band,

along with Blondie, Talking Heads, Television, Sonic Youth and The Ramones,

stand the rock world on its ear. Crudely recorded cassettes of these bands

reach hip kids’ collections around the country, and a musical explosion is

fomenting. And Horses is the match

that will light the fuse.

It’s Patti’s first studio album release, and it comes on a

silver platter—recorded at Jimi Hendrix’ Electric Lady Studio, produced by John

Cale, and released on Clive Davis’ big-clout Arista label. Patti, with her raw,

Chelsea-Hotel-stained poetry, her CBGB-honed wild looks and her

straight-from-hell punk eloquence, has won the hearts of Andy Warhol and New

York City. Now, with Clive’s powerful backing, she is about to win over the

rest of America.

Horses is the first punk rock album ever released on a major label. Fittingly, it is a masterpiece. The record makes all kinds of best lists, be it “Best Punk Album,” “Best Debut Album,” or “Most Influential Album.” In 2003 Rolling Stone rated it as the 44th best rock album of all time. It’s also often mentioned for having the best opening line in rock history. Side One/Track one is a Saturn-rocket take-off on Van Morrison’s Gloria that starts softly with a lonely, haunting piano, slowly riffing through Gloria’s chords. Then Patti’s vocal comes in, low in register, rich in tone, dripping with pain: “Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine…” In mere seconds Patti becomes transcendent, gripping listeners by the lapels and dragging them to new dimensions with whole new worlds of possibilities. I’ve listened to that opening segment dozens of times over the years, and it still takes me to those worlds. Every time.

In 1976, Patti Smith was more than just making waves. She was the wave. And she was coming to Bloomington

Mort Salt is Primo’s

music editor, a Midwest-condescending, ex-pat New Yorker. He’s a little older,

and considers himself to be a real pro. He’s not at all a fan of my writing

style. He complains that it lacks proper content and once derided it as

“unprofessional self-indulgence”. Leary of what he perceives to be my

propensity for poor preparation, he’s called me daily for the past week to make

sure I understood the enormity of this assignment, “not only to this

publication but also to the alternative community we serve.” He insists that I stop by the office to pick

up a portfolio of Patti’s news clippings that he’s amassed for my benefit.

Having no interest in press clippings, I let my answering machine take his

calls and steadfastly refuse to respond. It is my policy to avoid office visits

except for the essentials: dropping off articles (usually only slightly past

deadline) or picking up checks.

On Saturday morning, the day of the show, I waken to see

the answering machine already blinking with two messages. Steeling myself for

Mort’s harsh, boxing-announcer voice, which usually hits me like a hard-pitched

Brooklyn beanball, I tap the play button. Mort barks: “JB, I can’t believe you

still haven’t picked up those fuckin’ clippings. Have you even listened to the

album yet? Call me. Now!“

I must admit I take some pleasure hearing that trace of

panic edging into Mort’s voice. I laugh and say to no one, “Sure thing, numb

nuts”. I play the second message. Once again it’s Mort, but this time he comes

in with a high, hard one that catches me right on the earflap: “JB, if you

haven’t picked up those clippings by noon today, I’m pulling you off this

assignment. Vic’s gone for the weekend, so don’t think I can’t do it.” Well,

that gets my attention…

…About a half minute after leaving the office, I stuff

Mort’s big manila envelope, bulging with Patti lore, into an over-spilling city

trash can. Before turning away, I pause to look at the envelope, wedged

precariously in the overspill and glaringly visible to prying editorial eyes.

Staring at the obscene object, I contemplate my lack of preparation and feel a

ball-tingling surge of fear. “Pre-show

jitters,” I think. “Good.“

Truth is, Mort has it right. I know next to nothing about

Patti. My promo copy of Horses

remains intact in its shrink wrap. My notebook is devoid of well-engineered

questions. Even worse, I’ve never actually attended a punk rock show. Truly, I

realize Mort’s worst nightmare. But for this story, that’s the way I want it.

I’m no punk rock expert, so my best approach to this story is per my alter

ego–a card-carrying, law-breaking, whacked-out, knee-knockin’ Gonzo

journalist. As such, all those manila-wrapped clever facts are, at best, boring

and, in truth, irrelevant. I grab my notebook and jot down these words: “What

is important for me is to physically enter into the story, to live the story–to walk, talk, assault

and gestalt the story—by whatever means necessary.”

I contemplate my brave bit of prose. I imagine the

balancing scale of justice and place those brave words in the left tray. In the

right tray I place a cold, hard fact: If I fail

to enter into the story, I’m left with squat. I take my hand off the cold fact

and watch the scale dip to the right. More tingling balls. I need

fortification, and since I’m giving up booze, I turn to my heroes.

Gonzo is the doctrine of my hero #1, Hunter S. Thompson. I

don’t copy Hunter, but I do emulate him. So far in my budding career, it’s

stood me well. I’ve already seen two of my Gonzoid stories go out on the AP

wire. That’s pretty much like finding the Holy Grail in my world. AP wire

stories are sent by Telex to every major publication in the world–and quite a

few minor ones too. Many of these publications ran my pieces, and I got a nice

fat check from each one that did so. The memory of those fat checks, reaped at

the cost of a few cheap sheets of typing paper, is indeed fortifying—but that

isn’t enough today. The tingling abates, but doesn’t cease entirely.

I turn to hero #2, Jack Backer, the faculty adviser for The Indiana Daily Student. IDS isthe Indiana University student

newspaper, the venerable great white way of Hoosier journalism where I learned

to be a good little journal-bot. Thanks to Jack, I learned all that crap and a

whole lot more. Backer is a big fan of Hunter S and his “new journalist”

comrades, But Jack doesn’t see much new about it. He once said to me, “Take

Ernie Pyle – he was nothing if not a new journalist. He hung his ass out, down

and dirty, right on thefrontlines, European and Pacific theaters. Hunkered down in foxholes with the GIs and

shared the misery, terror and utter futility of war with all of America. How’s

that for some Fear and Loathing?”

“And that’s just it,”

I tell myself. “You don’t get the really

good stuff without taking chances.”

What? Me tingle? Feeling thus reassured in my insanity, I nevertheless pluck the envelope from its dangling perch and stuff it into my knapsack. My thought bubble says, “Sometimes that stuff comes in handy when you’re writing up your story”

Before closing up the knapsack, I check its contents, the

tools of the Gonzo trade: seven ink pens in various degrees of depletion; a

battered reporter’s notebook whose outer surfaces are blanketed by a blizzard

of scribbled names and telephone numbers, whose swirling, intertwined,

poly-chromatic patterns bring to mind Jackson Pollock on crack; my vintage Ray

Ban Aviators, snug in their fine leather case; one unopened half pint of Cuervo

Gold Tequila for medicinal purposes only; a black faux-leather card case that

houses my prized collection of fake press credentials and business cards; two

Fender guitar picks (one medium, one thin); three Durex condoms; one Zero candy

bar. At the bottom of the pile lies the pièce de résistance, my slender Norcom

550 mini-cassette recorder, secured in its leatherette sleeve that is almost

exactly the same size as the Aviators’ case. Assessing the collection, my

thought bubble opines, “Weak on

recreational drugs, but it will do!” I tuck the recorder into my shirt

pocket, close and shoulder the knapsack, and pedal on over to the Poplars.

I am no stranger to the hotel. Vic and I, along with a few

other budding Ernie Pyles, started out Primo

Times in a print shop that sits directly across Seventh Street from the

Poplars’ front doors. It’s a straight shot through the lobby to the back doors

and then through the parking garage to the Runcible Spoon, Bloomington’s

premiere coffee bistro. Coffee being the life blood of journalism, we traveled

that conduit frequently in quest of the Runcible’s glorious, fresh-roasted

brew. By the time we put our third issue to bed, I was on a first name basis

with Tony, the evening security guard.

The lobby, I recall, has about as much character as a laundromat. The style is more institutional than decorative, which is to say, horrible. I remember occasionally seeing signs for events in the ballroom, and these are inevitably forensic seminars. I came to realize that the Poplars is pretty much cop central for Indiana. With that understanding, the décor began to make sense. Of course! Cops feel right at home in such bleak confines. Put in a donut stand, and they’d call it heaven.

On this Saturday in the summer of 1976, the lobby barely

resembles the forensically-friendly place I remember. For the Poplars, it’s

Freaky Friday come a day late. A scene is unfolding, one heretofore unknown in

provincial Bloomington. Oh, there are still plenty of cops in the lobby.

They’re plumply parked, leaning against walls and columns all around the huge

room. Frowning. Disdaining. Leaning with hugging arms crossed, firing arms

holstered, and both arms ready for action. An army in blue protecting its

sacred ground. Against…

…An army in black. Swarming brigades of roadies, techies

and merch pushers. A platoon of apparent non-combatants gathered in

conversational gaggles to watch the circus unfold. Skeleton-thin people.

Clothes shredded with strategically random precision to expose small expanses

of snowy flesh and vibrant tattoos. Dynamic vectors of spiked hair, either dyed

inky black or sprayed fluorescent purple, red, pink, orange and green. Untanned

faces coated heavily in macabre Goth make-up to channel ghoulish, ceremonial

masks. Raccoon eyes corralled by fences of heavy black kohl. Piercings

everywhere, especially the ears, where scores of implanted metal trinkets serve

to bear semblance to miniature ear-shaped tea tables set with silver cutlery.

The observers, those not there for heated labor, wear their obligatory

black-leather jackets festooned with legions of silver chains, cloth patches

and pinback buttons. The backs of the jackets are dark message boards with band

names, obscenities and symbols of anarchy hand-painted in angry slashes of

white. The ones there to work are stripped down to their well-ventilated,

hole-filled t-shirts, most of which are imprinted with pictures of punk bands

whose members look just like themselves. Curiously, their heavy black boots

bear no small resemblance to the cops’ footwear. Middle ground? Not!

I spot a group of people who, clad in comfortable every-day

attire, don’t look like the band people on the t-shirts. They are, of course, a

band; MX-80 Sound, the mad-scientist art/noise savants who will share tonight’s

bill with Patti. They’re a Bloomington band, and I know them, especially the bassist,

Dale Sophiea, who is Primo’s movie

editor. I approach them, and soon I’m immersed in an animated discussion re:

the merits of Andy Warhol with enigmatic guitar maestro Bruce Anderson. Bruce

is a unique man, one who once, to maximize blood flow to his brain, rigged up a

special harness so he could hang from the ceiling, upside down, in full lotus

posture, and practice guitar.

Though I’ve known Bruce for years, this is the first time

we exchange more than a couple words. Talking with this shy, soft-spoken,

left-brained genius from Oolitic, Indiana is a rare treat. He prefers to let

his guitar do the talking, and unlike his mouth, it talks real, real loud.

Bruce is at heart an art-loving nerd, a profoundly cool dude who never spends a

second trying to be cool. He’s also

one of the best and most innovative guitarists the world has ever known, one

who will, possibly, become much more well-known as time passes.

I say possibly because he, at present, has a considerable

following. MX-80 relocated to Frisco in 1978 and signed with The Residents’

self-owned label, Ralph Records. That got their music out to the world. They’ve

prospered since, especially in Europe. They are world-renowned in their field,

and, remarkably, they’re still making records and playing shows.

~

Perhaps I’ve dawdled too long with Bruce in this story. Or

perhaps not. But I definitely dawdled too long with him on this Seditious

Saturday. I recall, perhaps too late, that I am due at a presser with Patti in

five minutes. I rush, on time, to the conference room where it is to be held,

only to find the room empty and unlit. Confused and panicking, I trot back to

the lobby, and, luckily, I see Tony, the friendly security man, leaning

cross-armed in his favorite spot. Slightly out of breath, I ask Tony if he

knows anything about the press conference. He says, “Oh man, she just moved the

whole thing up to her penthouse. Room 800. Come on! I’ll take you up there!”

We hurry to the elevator and ride to the eighth floor. Tony

keys the lift doors open and leads me down the hall toward Patti’s suite. I’m

glad to see that the door is still wide open. As we draw near, Tony stops me

with a tap to my shoulder, leans close, and whispers confidentially, “Good luck

with that one, man.” I don’t know what the hell he means, so I just say,

“Thanks, Tony. You da man.”

I pause in the doorway, realizing that, even though I’m

only a couple minutes late, the conference has already begun. I eye the big

room. It’s a good fifty feet from where I stand to the balcony’s sliding door.

It’s easily thirty feet wide. Midway along the wall Patti sits in a half lotus

on the end of a king-sized bed. She’s wearing a vintage black men’s sports coat

with narrow lapels over a black-and-white checked vest. The vest is unbuttoned

just enough to show she’s wearing a black, see-thru bra beneath. Skin-tight

leather pants and bare feet complete the outfit. Beside her on the bed lies a

Middle Eastern tabloid with headlines in pretty, looping Arabic. Behind her and

leaning against the pillows lies a battered, black Fender Mustang guitar. She

sits facing out over a single row of about twenty reporters who sit before her

cross-legged on the floor. They are all like me: young, shaggy-haired men with

notebooks and mini-recorders. I recognize only a few of them.

The guy seated nearest the door is asking a very long

question. Patti angles her long, thin, frowning face toward me and slowly looks

me up and down. Interrupting the reporter’s question, she says loudly to me,

“Hello, Mister Late. I should fucking kick you the fuck out of here for being

late, Mister Late.” Before she can do that, I quickly dive over to seat myself

beside the interrupted reporter. My butt barely hits the carpet before she

says, “Not there, Mister Late.” I stand, and she points toward the balcony,

saying, “All the way to the end, and sit cross-legged, Indian-style, if you

please.”

I stand, the subdued chorus of chuckles from the press

corps adds to my chagrin. My thought bubble says: “Fuck! This is exactly the

start I didn’t need!” I see directly before mea set of French doors opened to a short, cabinet-lined passage

that leads to another large room. In there I see luxurious living room

furniture and rock stars gathered around a coffee table. They appear to be

snorting cocaine. I think for just a second about continuing ahead into the

naughty boys room, but think better of it. Not following Ms Smith’s

instructions could turn bad. I take the good turn and begin my slightly

cautious saunter past her to my designated spot. As I pass before her, she

catches my eye. Maybe it’s just wishful thinking, but I think that when our

eyes meet, I see a little sparkle in hers.

Mister Interrupted By Mister Late resumes his question, and

what a question it is. He goes on and on with authority, sometimes glancing

down to refer to his notes. By the time he finishes I have more than quadrupled

my knowledge of Ms Smith, who, speaking of, just sits staring glumly at the guy

for several long seconds.

Finally, in a barely calm voice she says, “You know,

really, that’s not even a question. That’s just you showing how incredible you

are and how fucking much you know. I’ll tell you one thing you don’t know. You don’t know rock and

roll. If you did you wouldn’t be asking fucking show-off questions. You have no

business writing about rock and roll, because you are SO-O-O not fucking rock and roll. Get the fuck

out of here, please.”

The kid just sits there, not believing his ears. Suddenly,

as if touched by a live wire, Patti goes off. She leaps from the bed and stands

screaming obscenities at the dude. Mister Interrupted By Mister Late aka Mister

Not Fucking Rock ‘n Roll just sits there paralyzed, so she throws herself at

him like a Tasmanian devil. But before she can seriously harm her victim, a man

shoots out from the hallway and grabs Patti around the waist. He lifts her off

the floor, and she, with legs and arms flailing, continues screaming

obscenities with a flow to rival the St. Lawrence Seaway. Given this reprieve,

Poor Mister Interrupted (etc.) wisely flies out the door.

Improbably, Patti calms down almost instantly and resumes

her Indian-style perch on the end of the bed, acting as if nothing absolutely

insane has just happened. The guy that saved Mister Interrupted takes up a

position near the bed. I, for one, am glad to see that. He is a slightly older

dude who has the look of a musician. And well he should. I find out later that

he’s Lenny Kaye, formerly of MC5 and currently lead guitarist of the Patti

Smith Group. He is definitely fucking

rock and roll. Later that day I get a great and hilarious interview with him.

But that’s another story.

Patti turns to the next reporter in line and asks for his

question. He stands up. She tells him to sit back down. Undeterred, he

announces, “I actually have two questions.” Ms Smith replies, “I have one

question. How long will it take you to get the fuck out of here?” Remembering

Mister Interrupted (etc), he’s out in record time.

A disturbing pattern emerges. Serious young man asks

serious, thoughtful question. Serious

young man gets told he’s not fucking rock and roll. Serious young man gets sent

packing. Next! She mows down half of

my colleagues with her Tommy-gun tongue.

I hate it, and I hate her. Sure, these guys aren’t rock and

roll. Sure, we’re a bunch of self-absorbed nerds–but so too are a hell of a

lot of great rock and rollers. They just plug in amplifiers instead of

typewriters. Friggin’ Marilyn Manson, once you get to know him, he’s just a

nerd with an electric guitar and a comely make-up artist. These banished kids

will go to the show, give it their full attention, and then go home to write a

brilliant, inciteful review without even mentioning shrewish Ms Smith’s

disgraceful antics.

~

After she’s dispensed with half of the assemblage, Patti

announces that she needs a break and heads off into the adjoining room. “Probably to powder her nose,” I bubble.

Several of the remaining victims take advantage of the hiatus and head

post-haste out the door and to safety. In the end there are only two of us,

rooted to our spots, too intimidated to sensibly move closer to the throne. I

seriously contemplate making it a singleton. I have no idea what I will say

when she asks for my question. “You think

those well-prepared guys’ questions sucked? Get a load of this one, bitch!” I

finally decide to stay, thinking, “This

so-called press conference is my story. I’ve got to stay and ask my

question. Maybe she’ll get past Lenny and punch my lights out. Now that would

be a story!”

Patti returns looking slightly more subdued but not a whit

less malevolent. Her homely face is as ugly as a witch’s fist. She’s removed

the sports coat and unbuttoned the vest completely to reveal a good portion of

her breasts, visible through the translucent bra. I try not to look, but they

are quite beautiful. She resumes her throne, lights up a fat joint and passes

it to Lenny. The fragrant smoke wafts about the room bearing the distinct and

heavenly aroma of some really good shit.

She turns to us, her final two victims, and, neither inviting us to move closer

nor, most uncivilly, offering us a hit off the joint, points a lazy finger

toward my companion.

He asks his intricate question, and as he finishes Patti’s

head slumps wearily downward. This guy saves a little face by asking, “Not rock

and roll? Get the fuck out?” She merely nods without looking up. After he’s

gathered his gear and left, Patti, without raising her head, says to me rather

gently, “Alright, Mister Late. What’s your fucking question?”

At that point I still have nothing. But I also have nothing

to lose. So I say, “May I please have a hit off that joint?”

I watch closely as she slowly raises her head to reveal, to

my utter shock, a little Gioconda smile. A transformation occurs before my

eyes. Her body language softens to sensuous, and I swear she is glowing,

exuding a soft blue light. And her face! My God! She is so beautiful!

She slides off the bed, walks over to me and passes me the

joint. As I take my righteous toke, she starts giggling. Then she says to me:

“Now that, was a really good fucking question.”

THE END

.