The King of the Bs Gets Serious ● by Craig J. Clark

[He was fast. He was cheap. He was looking for thrills. Long before the DIY culture became fashionable, Roger Corman was doing it himself, making feature length movies with little money but lots of ingenuity. He is the patron saint of independent cinema and he will be visiting Bloomington on April 18 and 19.]

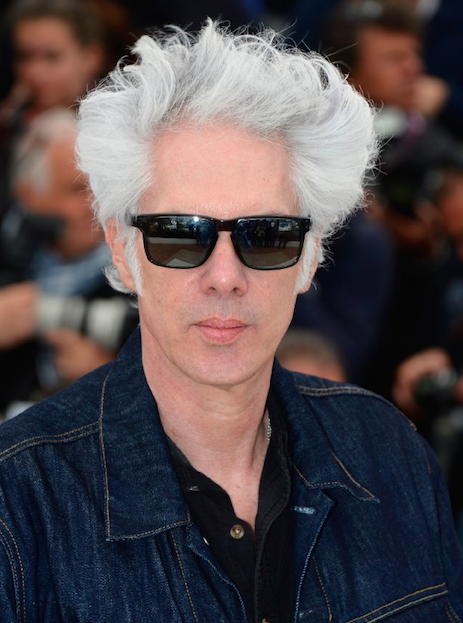

For some, the Honorary Academy Award producer/director Roger Corman received in 2009 “for his rich engendering of film and filmmakers” was a moment of long-overdue recognition from an industry that seemed loath to acknowledge the impact he’d had on it over the course of his six-decade career. For others, who only know his name from the handful of his ’50s B movies that made their way onto cable’s Mystery Science Theater 3000 in the ’90s, it must have come as something of a surprise that the Academy would give him an award at the same time as acting legend Lauren Bacall and influential cinematographer Gordon Willis. Even putting aside all the filmmakers who got their start at Corman’s production company New World Pictures in the ’70s and beyond, though, the amazing run of films he made in the ’60s would be worth celebrating.

As a director, Corman tried his hand at just about every genre, beginning his career in 1955 with the westerns Five Guns West and Apache Woman, the crime drama Swamp Women, and the sci-fi parable Day the World Ended. For the rest of the decade he cycled between those subjects and other drive-in friendly fare about juvenile delinquents, rock and roll, Viking women, gangsters, and teenage cavemen. He didn’t tackle a war film, though, until 1960’s Ski Troop Attack, which Corman filmed in tandem with Monte Hellman’s debut Beast from Haunted Cave, which he executive produced.

Shot on location in South Dakota, Ski Troop follows a five-man recon patrol scouting the German countryside in the winter of 1944 in advance of General Eisenhower’s final push. The patrol is led by lieutenant Michael Forest, who likes to do things by the book and is constantly being dogged by sarcastic sergeant Frank Wolff, who’s eager to fight and resents Forest’s officer training. In order to differentiate between the three privates under them, screenwriter Charles B. Griffith makes one a Yankee, one a Southerner, and one a radio operator who gets killed early on. The only other major character is the hausfrau whose cabin gets raided for supplies when their rations run out, and to further save money Corman himself plays the distractingly dubbed commander of the German ski patrol in pursuit of our heroes when they set about destroying a strategic bridge. The battle scene that follows clearly illustrates how much he was stretching his budget, but you’ve got to admire the guy for trying to make a war film for pocket change.

Thankfully, Corman had a bit more money to work with when he made 1960’s House of Usher, the first of seven Edgar Allan Poe adaptations he made for American-International Pictures. The film also represents Corman’s first collaborations with screenwriter Richard Matheson and star Vincent Price, who would become a fixture of the Poe cycle as well as a few other films Corman made during the same period. Price plays Roderick Usher, a sinister, white-haired recluse who believes his family line is doomed and tries to stonewall Bostonian Mark Damon when he arrives at the titular residence and announces his plan to take Usher’s sister Madeline (Myrna Fahey) away with him. The only other living character in play is Usher’s faithful servant (Harry Ellerbe), but in a lot of ways the most important character is the house itself, which shudders from time to time and appears to be ready to collapse at any moment. No matter how annoyed he gets at Price’s insistence that he leave, Damon can’t deny that his life is in danger as long as he stays.

Corman may have been known for his ability to churn out movies quick and on the cheap, but House of Usher and the others in the series show what he was capable of given a little more time and money. It also benefits greatly from having been shot in CinemaScope (which cinematographer Floyd Crosby uses to enhance the atmosphere) and Daniel Haller’s sumptuous production design really stands out thanks to the decision to spring for Technicolor. It’s no surprise that the National Film Preservation Board chose to add House of Usher to the National Film Registry in 2005. It’s definitely one that has stood the test of time and laid the groundwork for more compelling films to come.

Another Corman film that has had remarkable staying power is 1960’s The Little Shop of Horrors, which became a cult favorite long before it inspired an off-Broadway musical and big-budget remake. Today, it’s probably most well-known for the three-minute cameo by Jack Nicholson as a masochistic dental patient, but his character is barely an afterthought. The actual star is Jonathan Haze as the hapless Seymour Krelboin, creator of hybrid plant Audrey Jr., which turns out to have unusual tastes, with Jackie Joseph as the ever-sunny Audrey, Mel Welles as the Skid Row florist who lets his greed get the better of him, and Corman regular Dick Miller (who had previously starred in 1959’s A Bucket of Blood as a wannabe beatnik artist who turns his murder victims into art) as a flower connoisseur who prefers eating in “out-of-the-way places” and is “crazy about kosher flowers.” For a film Corman reportedly shot in two days on a bet, Little Shop is a real winner.

Later that year, Corman traveled to Puerto Rico to make a trio of movies. (Actually, he only planned on making two, but the script for a third was hastily thrown together to make the most of the location shoot.) First out of the gate was Last Woman on Earth, a post-apocalyptic adventure story which Corman had enough faith in that he put up the extra money to shoot it in color. Written by first-time scripter Robert Towne (who would later write Chinatown), it stars Betsy Jones-Moreland as the neglected wife of unscrupulous businessman Antony Carbone, who is vacationing in Puerto Rico (and gambling on everything in sight, including the cockfights) while the U.S. government is investigating him. He’s also accompanied by his lawyer (played by Towne under the pseudonym Edward Wain), who wants to talk business but gets roped into a scuba diving expedition. It’s a good thing he is, too, because it’s while the three of them are underwater that the world goes kablooey. After they surface and discover that they’re the only humans left, our three heroes make for shore and begin building a new life – one that is immediately beset by conflict as the last two men on Earth aren’t interested in sharing the last woman.

Carbone, Jones-Moreland, and Towne also show up in 1961’s Creature from the Haunted Sea, the aforementioned hastily-thrown-together film which was written by Corman’s frequent scribe Charles B. Griffith. It’s one that Corman highlights a number of times in his 1990 autobiography How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime, so it must have been one of his favorite movies. It’s certainly one of his more offbeat efforts. In it, Carbone plays a crook who agrees to help Cuban nationalists smuggle the nation’s treasury out of the country on his boat in the wake of Castro’s revolution. Aiding him are his moll (Jones-Moreland), her dim-witted brother (Robert Bean), and his henchman (Beach Dickerson), who inexplicably communicates mostly in animal sounds. Also along for the ride are an inept government agent (Towne, again using the pseudonym Edward Wain) and a brace of Cuban soldiers brought along to guard the treasury. Carbone plans to double-cross the Cubans, killing them off one by one and blaming the deaths on a made-up sea creature, but when the creature turns out to be real, he realizes he’s out of his depth.

During his two decades in the director’s chair, Corman only ever made one sword-and-sandal epic – 1961’s Atlas – and it’s easy to see why. Filmed on location in Greece, which he presumably figured would give him all the production values he could ever want, Atlas stars Michael Forest as the title character, an Olympic wrestler/philosophy student recruited by the evil Praximedes, Tyrant of Seronikos (Frank Wolff), to fight the champion of neighboring kingdom Thenis, which is ruled by wise old Telektos (Andreas Filippides, helping to fill the quota of Green actors in the film). Atlas takes some convincing, though, which is why Praximedes throws his ex-lover, high priestess Candia (Barboura Morris), at him. When the film gets to the battle scenes, they’re staged very poorly and edited most chaotically to cover for the shortage of extras. Corman even put on a tunic himself and entered the fray alongside mainstay Dick Miller and screenwriter Charles B. Griffith, but their efforts are largely for naught.

Returning to America and AIP with his sword between his legs, Corman embarked upon the second entry in his Poe series, 1961’s Pit and the Pendulum, which also boasted a screenplay by Richard Matheson. It stars Vincent Price as Nicholas Medina, the haunted son of one of the Spanish Inquisition’s most notorious torture enthusiasts, who is in mourning after the sudden death of his wife Elizabeth. John Kerr is Elizabeth’s brother Francis, who travels to Nicholas’s desolate castle to find out how she died (and is fairly blunt about it). Barbara Steele (fresh off starring in Mario Bava’s Black Sunday) is the lovely Elizabeth, glimpsed in distorted flashbacks and supposedly returned from the grave to torment Nicholas for entombing her prematurely (apparently one of Poe’s biggest fears since it features in so many of his works).

■

It takes a while for the film to actually reach the scene with the pit and the pendulum, but it’s a corker of a finale and Corman and Matheson effectively build the sense of the dread in the 70 minutes leading up to it. The scenes in the torture chamber are especially well-done, with Corman able to evoke the evil of the Spanish Inquisition without actually showing anyone being tortured. If I have one complaint about the film, it is that Barbara Steele’s part is so small, but that’s what you get when you play a character everybody believes is dead.

Vincent Price wasn’t available when it came time for Corman to make his next Poe film, 1962’s Premature Burial, so he hired Ray Milland to play his tortured lead instead. The tone of the film is set in the opening scene in which Milland is present at the exhuming of a grave where it turns out the occupant was buried alive. This awakens his gravest fear since he has long believed that his father was entombed prematurely, so Milland attempts to break his engagement to fiancée Hazel Court, but she talks him into going through with the wedding. Instead of going away on their honeymoon, though, Milland insists on staying at home so he can design and build a tricked-out mausoleum to make sure he doesn’t fall victim to the same fate. (The scene where he proudly demonstrates its features is one of the highlights of the film.)

Court tries to get help for her husband, but this is pre-psychoanalysis, so her doctor friend Richard Ney can only diagnose that he is disturbed, a suspicion echoed by Milland’s sister Heather Angel, who insists that their father wasn’t buried alive. Then there are the two gravediggers, played by John Dierkes and Dick Miller, who keep popping up and scaring the wits out of him. It’s no wonder Milland starts getting rude and ill-tempered. Milland the actor must have enjoyed working with Corman, though, since he returned the following year to play the lead in X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes.

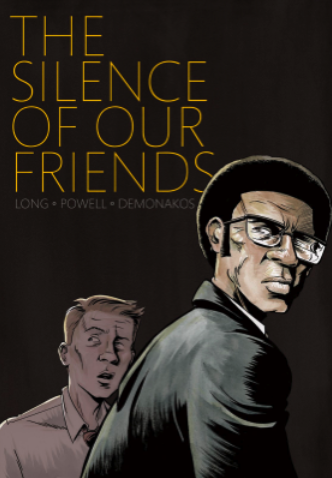

Before that, Corman took time out to make 1962’s The Intruder, a hard-hitting social drama starring William Shatner as a representative of the Patrick Henry Society who arrives in a small southern town to fight racial integration of the local high school. Following an unbroken string of financial successes, this was the first film Corman made that didn’t immediately reap a profit, which is why he retreated to the exploitation films he was known for and didn’t look back. The major studios could afford to make the occasional prestige film for the sake of posterity; Corman needed each film to make money so he could go on and make the next one.

Long before he became known for his hammy acting, Shatner puts in a credible performance as the anti-integrationist (who’s also rabidly anti-commie and anti-Semitic to boot) who talks a good talk, but can’t control the situation once he’s stirred up the hornet’s nest. He’s ably assisted by Frank Maxwell as a newspaper editor who’s against integration, but finds Shatner’s methods even more distasteful, Beverly Lunsford as Maxwell’s daughter, who goes to the high school that’s being integrated, Robert Emhardt as a rich southern gentleman who gives Shatner crucial backing, Leo Gordon as a traveling salesman staying just down the hall who unwisely leaves his wife Jeanne Cooper on her own, and Charles Barnes as one of the black students reluctantly going to the white school, much to the majority population’s consternation. To illustrate this, Charles Beaumont’s screenplay (based on his novel) is peppered with racial slurs (I counted 21 uses of the n-word alone), some of which were voiced by local nonprofessionals who were probably all too comfortable using them. While the film may lack subtlety, one can’t deny its power.

Following the Vincent Price-less Premature Burial, Corman made it up to him by giving him not one, but three choice roles in his next Poe film, the 1962 anthology Tales of Terror. In the first part, based on “Morella,” he plays the boozing Locke, whose decrepit house is visited by his estranged daughter, who he has always held responsible for the death of his wife. The house is in such disuse that even the cobwebs have dust on them. The second part, which combines elements of “The Black Cat” and “A Cask of Amontillado,” pits Price against Peter Lorre, who plays a disreputable drunk who hasn’t worked in years, but has a knack for identifying wines. Price plays Fortunato, an effete wine expert who takes up Lorre’s challenge at a wine tasting and then takes up with his wife, spurring Lorre on to his revenge. The last and best segment, “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar,” casts Price as the dying Valdemar, who employs mesmerist Basil Rathbone to relieve his pain and strikes a bargain on his deathbed that he comes to regret.

That same year, Corman took time out from his Poe cycle to make Tower of London, a Shakespearean pastiche that takes the basic plot of Richard III and grafts elements of Hamlet and Macbeth onto it. In it, Vincent Price plays the deformed Richard of Gloucester, who will do whatever is necessary to ascend the throne, including literally stabbing his own brother Clarence in the back. Egged on by his wife Anne, doing her best Lady Macbeth impression, delivering soliloquies of self-doubt and seeing ghosts like a certain Prince of Denmark, and generally hamming it up, Price’s Richard is far from a model of restraint. Still, he must have relished the opportunity to essay the role, having played Clarence to Basil Rathbone’s Richard in one of his first films, 1939’s Tower of London.

Corman kicked off 1963 with The Young Racers, a melodrama about the lives of race car drivers on and off the track. It stars Mark Damon as a writer who sets out to do an exposé on philandering champion William Campbell, especially when Campbell sets his sights on Damon’s secretary (and fiancée) Luana Anders. And he’s not the only one has an axe to grind – there’s also Campbell’s sourpuss brother Bob, played by his actual brother (and the movie’s screenwriter) R. Wright Campbell, and self-proclaimed “critic of life” Patrick Magee, who has waited a long time to get his revenge (just as we have to wait a long time for him to even show up in the picture).

The Young Racers was a major international production by Corman’s standards, with extensive location shooting and plenty of actual race footage. As a result he had plenty of help on hand, including Charles B. Griffith as assistant director, Robert Towne as second assistant director, a young Menahem Golan as production manager and assistant director, and an even younger Francis Ford Coppola as sound man and second unit director. Incidentally, it was during this production that Coppola convinced Corman to give him the money and three of his stars to shoot Dementia 13, the calling card he used to move on to bigger and better things. Sometimes the ones who learned the most from the Roger Corman School of Filmmaking were the ones who graduated the quickest.

Made somewhat late in Corman’s Poe cycle, 1963’s The Raven was the last one to be written by Richard Matheson, who had a free hand to develop the story however he saw fit and chose to play it for comedy. He was also able to tailor the parts for the film’s stars, namely Vincent Price (as a retiring magician who has been in mourning since the death of his wife Lenore), Peter Lorre (as a belligerent and frequently drunk magic-user who arrives on Price’s windowsill in the form of the titular bird) and Boris Karloff (as an evil sorcerer keen to learn Price’s secrets).

■

The cast also includes Hazel Court as Lenore, who’s not quite as dead as Price thinks she is, Olive Sturgess as his beautiful daughter Estelle, and Jack Nicholson as Lorre’s bumbling son Rexford, the kind of prototypical gawky goofball usually played by Jonathan Haze. On the whole, the film is a great deal of fun, with a certain amount of physical comedy (as in the scene where Lorre has only partially been restored to his human form) and actors who are clearly enjoying themselves very much. And it was at the end of this film’s shoot that Corman initiated The Terror, which was started purely because he had the standing sets and wanted to get more use out of them.

Released in 1963, The Terror is a bit of hodgepodge in that it features scenes shot by Corman, associate producer Francis Ford Coppola, location director Monte Hellman, writer Jack Hill (who gets a screenplay credit along with Leo Gordon) and even star Jack Nicholson, who plays a French soldier during the Napoleanic wars who gets separated from his regiment and comes upon the beautiful Sandra Knight (Nicholson’s wife at the time) when he’s searching for water. She shows it to him, which proves that if you lead a Napoleanic soldier who was been separated from his regiment to water, you can make him drink.

Top-billed, though, is Boris Karloff, who plays the Baron Victor Frederick Von Leppe, which is quite a mouthful for any actor. For 20 years, since the death of his wife Ilsa, the baron has kept himself locked away in his castle, attended only by his faithful servant Stefan (Dick Miller), the bearer of the bulk of the exposition. Also on the baron’s property, for reasons of their own, are a witch (Dorothy Neumann) and her supposedly mute servant (Jonathan Haze). At various points, nearly everyone tries to convince Nicholson that he is mistaken when he claims to have seen Knight, but they also bristle at the mere mention of the name Eric. Eventually it comes out who Eric is, but before we reach that point there are a lot of scenes of Nicholson wandering around the castle, occasionally bumping into Karloff or Miller and demanding that they explain what’s going on. As the audience’s surrogate, he’s only doing his job, but there are times when his behavior borders on Ugly Americanism – and he’s supposed to be French!

Corman returned to the present day with 1963’s X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes, which is one of his most ambitious and, in many ways, most successful films. Ray Milland stars as a scientist working to expand the range of human sight who experiments on himself and finds that his formula works all too well, with Diana Van der Vlis as a representative of the foundation that is funding his work – and which chooses not to continue funding it despite his breakthrough. His grant terminated, Milland is forced to scrape by as pierside attraction Mr. Mentallo, with Don Rickles as his barker. Rickles quickly catches on that he’s no ordinary mentalist and sets him up as a healer, but Milland has no illusions about what his powers mean.

As time goes on and Milland keeps applying his eye drops, his visions get more and more disturbing until he can no longer control what and how far he sees. (At one point he’s driving a car, but it’s hard to keep your eyes on the road when you can’t even see the road to begin with.) Eventually he winds up at a revival tent where the preacher informs him what the Bible says to do if your eye offends you, leading to a shocking freeze-frame.

X uses a range of photographic effects to depict the progression of Milland’s second sight, but sometimes the simplest effects are the most effective. And while the film plays things straight for the most part, there’s definitely something amusing about watching Milland half-heartedly dancing the twist at a swinging party where he can’t help but see everybody naked. (This being 1963, though, we only see people from the shoulders up or the knees down. It’s also six years before M*A*S*H, so at one point we get to see a virtually bloodless operation.) One can only imagine what Corman could have done with this material just a decade later.

Since he’s so closely associated with his Poe films, it’s less well-known that Corman was the first director to bring H.P. Lovecraft to the big screen, probably because AIP gave 1963’s The Haunted Palace the title of an Edgar Allan Poe poem instead of the Lovecraft story “The Case of Charles Dexter Ward” that it’s actually based on. No matter what it’s called, though, it does an admirable job of conveying the creeping dread that pervades Lovecraft’s work, even if its depiction of the dark forces is somewhat lacking.

Vincent Price plays Ward, who journeys to Arkham with his wife Debra Paget to claim his family’s estate, 110 years and one Poe stanza after his great-great-grandfather was tied to a tree and burned as a warlock. Upon their arrival in the perpetually fog-enshrouded town they ask for directions at the Burning Man Tavern, where they get a decidedly chilly reception from the townsfolk, led by Leo Gordon (in a scene that surely inspired the one at the Slaughtered Lamb in An American Werewolf in London). Finally, helpful doctor Frank Maxwell points them in the right direction and they show up at the house, which has been prepared for them by creepy caretaker Lon Chaney, Jr., thus setting the stage for history of repeat itself.

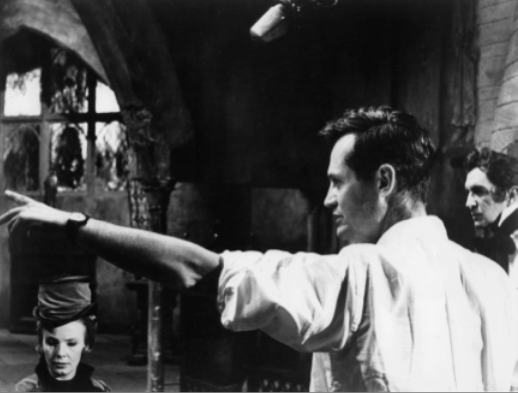

Corman’s penultimate Poe picture was 1964’s The Masque of the Red Death, easily the most sumptuous film he ever made. Written by Charles Beaumont and R. Wright Campbell, it also gave Vincent Price one of his meatiest roles as the decadent Prince Prospero, an avowed Satanist who locks himself away in his castle with dozens of equally loathsome courtiers while the Red Death ravages the countryside. Joining him in the service of Satan is Hazel Court, who seems all too eager to give herself over to the Prince of Darkness, and fighting against Price’s corrupting influence is innocent believer Jane Asher, who pleads with him to spare the lives of her lover (David Weston) and father (Nigel Green), who are intended to fight each other to the death for the amusement of Price’s guests. In terms of depravity, though, Price may be matched by the leering nobleman played by Patrick Magee with all the malevolence he can muster.

Corman Directs Price (r.)

■

All of the films in Corman’s Poe cycle are known for their lavish visuals and this one benefited greatly from the work of cinematographer Nicolas Roeg and production designer Daniel Haller. The most striking image in the film, though, is one of its simplest: the faceless personification of the Red Death sitting leaning against a tree dealing out tarot cards. Not only does it bring to mind Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (an admitted influence), but it’s an eerie depiction of the implacability and inevitability of death. Not even Prince Prospero, with all his wealth and power and influence, can escape that forever.

Leaving AIP once again, Roger Corman struck out on his own in 1964 and traveled to Croatia and Yugoslavia to film the World War II adventure yarn The Secret Invasion. Written by R. Wright Campbell, The Secret Invasion plays like The Dirty Dozen with half the cast and a fraction of the budget – only Corman actually beat that film to the punch by a few years (a practice he would come to perfect when he turned independent producer a few years later). In this case, the officer leading the mission behind enemy lines is played by Stewart Granger and the criminals he handpicks for the assignment are Italian thief Raf Vallone, IRA bomb-maker Mickey Rooney (complete with Irish accent!), brash young forger Edd Byrnes, emotionless killer Henry Silva, and pretty boy William Campbell. There’s even a love interest of sorts for Silva in the form of Slovenian actress Spela Rozin. This being a war film, though, they have little time to declare their feelings for each other, though.

Five years and seven films after he started it, Corman completed his Poe cycle with 1964’s The Tomb of Ligeia, which he shot in England from a screenplay by Robert Towne. This time out, Vincent Price plays Verden Fell, a man so obsessed with his departed wife, the Lady Ligeia (Elizabeth Shepherd), that he refuses to believe she is really dead. He even winds up marrying her double, the Lady Rowena (Shepherd again), after symbolically carrying her over the threshold of the abbey he calls home. After a globe-trotting honeymoon, during which they visit Stonehenge among other exotic locales and he comes out of his shell somewhat, they return to the abbey where he falls under its spell once again and she is menaced by a malevolent cat. (For once, the cat scares in a horror film are due to the cat itself.) Not a bad ending for the series, but the film does take its sweet time coming to a conclusion.

After taking a year off (something almost unheard for the workaholic), Corman kicked off his biker-movie boom with his 1966 film The Wild Angels. Written by Charles B. Griffith, it stars Peter Fonda as Heavenly Blues, the president of the San Pedro chapter of the Hell’s Angels, which was for the most part portrayed by actual Hell’s Angels. As the film opens, Fonda goes to see his buddy Loser (Bruce Dern) at the oil rig where he works. Rigger Dick Miller, a World War II veteran, takes exception to the Nazi paraphernalia Fonda wears and after an altercation Dern gets fired by the foreman. When Fonda announces that they’re heading south to Mecca to recover Dern’s stolen chopper, the whole gang goes along, always under the watchful eye of the police. Also along for the ride are Nancy Sinatra as Fonda’s old lady, Diane Ladd as Dern’s, and Michael J. Pollard as one of the gang.

Corman, Fonda & Bogdanovich (l. to r.)

■

While attempting to get Dern’s bike back the gang runs afoul of the Mecca police and Dern is shot while trying to escape. Fonda manages to bust Dern out of the hospital, but he’s in no condition to be moved and dies in Ladd’s arms. All that’s left to do at that point is ship the body back up north to Dern’s hometown of Sequoia Grove for a quiet funeral and respectful burial. (Yeah, right.) The church service turns into a drunken party and the locals turn out to watch the funeral procession and start a brawl at the cemetery. (Peter Bogdanovich, who was Corman’s assistant on the film, plays one of the curious locals who gets the crap kicked out of him.) The whole film is shot in a striking cinéma vérité style, which was imitated (usually very poorly) by the hordes of biker films that followed in the wake of its massive success. One thing is certain: the last thing the film does is make the life of a biker look glamorous.

In 1967, after operating independently or for AIP for his whole career, Roger Corman got to make his first film for a major studio, namely 20th Century-Fox, which produced The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, a fact-based account of the events leading up to that fateful February 14th. Written by Howard Browne, the film stars Jason Robards as a cigar-chomping Al Capone, who’s eager to shut down “Bugs” Moran (Ralph Meeker), the upstart head of Chicago’s North Side mob and a major thorn in his side. Throughout the film (and with the help of the voice-over narration), we’re introduced to the other major players, including George Segal as one of Moran’s enforcers, Jean Hale as Segal’s trampy wife, Clint Ritchie as the architect of the massacre, and Bruce Dern as a mechanic for Moran’s organization who picks the wrong day to do some auto repairs. And since the events depicted in the film are a matter of record, in lieu of suspense Corman and Browne use the narrator to reinforce the inevitability of what will happen when seven of the characters reach “the last morning of his life.”

With a major studio’s resources at his disposal, Corman was able to successfully evoke the period setting on a scale he hadn’t been able to previously, with lots of classic cars and clothing helping to bring late-’20s Chicago to life. He was even able to get realistic-looking snowfall for the day of the titular event, which must have seemed like pure extravagance to someone accustomed to filmmaking on the cheap. As well-mounted as the end result is, though, Corman chose to return to the world of the independents.

People generally don’t think “experimental filmmaker” when they think of Roger Corman, but when he made The Trip in 1967 he was pushing the bounds of what was expected not only of a Corman picture, but commercial cinema in general. The photographic effects that were used in X were like a dry run for some of visuals Corman and his crew conjured up to depict what it’s like to be high on LSD, and the kaleidoscopic editing techniques put it squarely in Point Blank territory. Written by Jack Nicholson, the film stars Peter Fonda as a commercial director at an impasse in his life who decides the way to find some insight is to drop some acid. All goes well at first, with his friend (a heavily-bearded Bruce Dern) acting as his guide and telling him he’s “into some beautiful stuff, man,” but then the trip takes a scary turn and Fonda gets spooked.

The film also features Susan Strasberg as Fonda’s soon-to-be ex-wife, who figures into some of his visions, Dick Miller as the bartender at the psychedelic club where Fonda meets Dern, and Dennis Hopper as the dealer they buy the acid from. One of the images the film keeps coming back to is a pair of hooded figures on horseback who give chase to a Fonda in vaguely Renaissance-y garb. There’s also not one, but two dwarves, and a torture chamber set seemingly left over from one of Corman’s Poe films. The strangest scene, however, has to be the one where Fonda is put on trial by his own psyche. This is the place where he’s forced to come to certain realizations about himself, so it’s no wonder he isn’t eager to go back there once he’s out.

By this point in his career, Corman was growing disenchanted with AIP, which was starting to meddle with his films in a way they hadn’t previously. For one thing, The Trip is preceded by a bummer of a roller caption, with a stentorian announcer to drive home the message that this is not the sort of thing you should do at home. For another, they changed the ending, shattering the closing image as a way of showing that Fonda’s one trip on LSD had irrevocably damaged his life. Sure enough, it was only a matter of time – and the formation of New World Pictures – before Corman started calling his own shots for real.

[The 2011 documentary Corman’s World: Exploits of a Hollywood Rebel will be screened at the IU Cinema on Thursday, April 17, and Saturday, April 19. In between, Corman is scheduled to be present for a Jorgenson Guest Filmmaker Lecture on Friday and introduce screenings of 1966’s The Wild Angels, 1967’s The Trip, 1962’s The Intruder, and 1964’s The Tomb of Ligeia on Friday and Saturday.]

The Ryder ● March 2014