François Truffaut

The Man Who Loved Cinema ● by Craig J. Clark

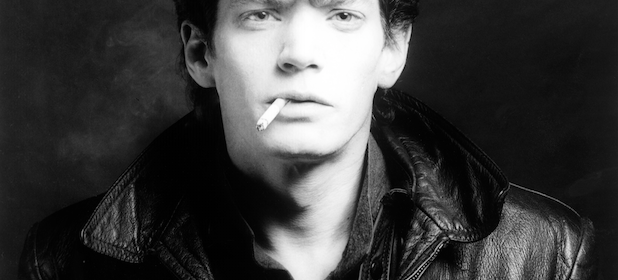

One of the leading lights of the Nouvelle Vague or French New Wave, François Truffaut died 30 years ago this month at the age of 52, having written and directed 21 features over the course of a career that spanned three decades. Before he had his breakthrough with 1959’s The 400 Blows, the first in a series of films detailing the adventures of Antoine Doinel (played by his onscreen alter ego, Jean-Pierre Léaud), Truffaut worked as a critic for the influential film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma. Afterward, he made such seminal New Wave films as 1960’s Shoot the Piano Player and 1962’s Jules and Jim, and wrote the original treatment for 1960’s Breathless, the debut feature of his Cahiers cohort Jean-Luc Godard.

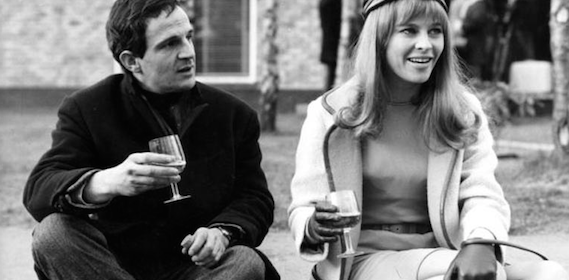

[Image at the top: Truffaut with actress Julie Christie.]

●

In the years that followed, Truffaut had big successes with the likes of 1973’s Day for Night, which won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film and the BAFTA Award for Best Film, and 1980’s The Last Metro, which won ten César Awards. What I’d like to highlight, though, are some of the lesser-known entries in his filmography, whose subjects run the gamut from marital infidelity to science fiction to Hitchcockian suspense to doomed romance. The one thing that binds them all together is Truffaut’s clear affection for his characters, however flawed they may be.

This was especially the case with Truffaut’s follow-up to Jules and Jim, 1964’s The Soft Skin, which wasn’t nearly as successful, but is a fascinating film in its own right. Based on a true story, it stars Jean Desailly as a respected author and editor of an academic journal who becomes infatuated with a much younger flight attendant and upends his life to be with her. Considering the flight attendant is played by Françoise Dorléac, it’s easy to understand why he’s so taken with her and fails to consider how their affair will affect his wife and their young daughter. As in the real-life case that inspired it, this leads to a tragic end for all concerned.

On The Set Of “The Soft Skin” With Françoise Dorléac

●

For a change of pace, Truffaut turned to Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, the first (and only) film he ever shot in English. Working with a large crew for the first time, Truffaut was able to fully realize Bradbury’s futuristic totalitarian state where reading books is illegal and firemen are employed to burn them when they are found. It’s a beautiful film to look at thanks to Nicolas Roeg’s sharp photography (which accentuates the reds that dominate the color scheme) and Bernard Herrmann provides a stirring score, but one gets the feeling Truffaut is constantly straining — and failing — to overcome the language barrier.

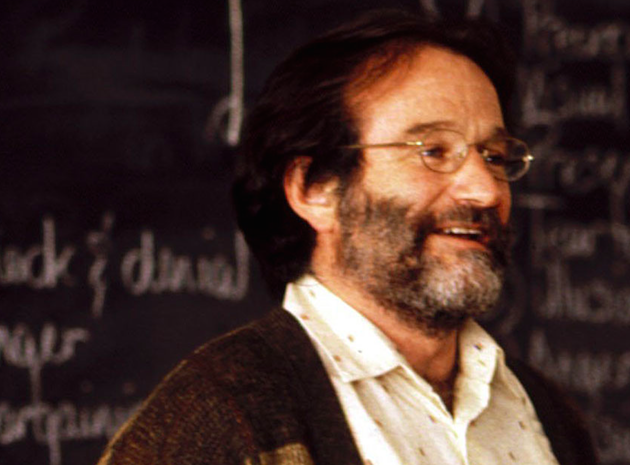

Of course, if Truffaut was uncomfortable writing and directing in a foreign tongue, that’s nothing compared to poor Oskar Werner, who previously starred in Jules and Jim and plays the film’s hero, Montag, in a halting German accent. He’s ably supported, though, by a cast of native-born English speakers like Julie Christie (who plays a double role as Montag’s vacuous wife and a teacher who lives nearby) and Cyril Cusack (as Montag’s captain). And even if it was done in the service of a story about the dangers of censorship, it’s still painful to watch the scenes of books (many of them masterpieces) being doused with kerosene and set ablaze.

Oskar Werner & Julie Christie

●

At Cahiers du Cinéma, Truffaut was a big proponent of the auteur theory, especially as it applied to Hollywood filmmakers like Alfred Hitchcock. After conducting a series of interviews with the Master of Suspense that resulted in the seminal book Hitchcock/Truffaut, he was inspired to take a couple stabs at the genre himself, first with 1968’s The Bride Wore Black and then with 1969’s Mississippi Mermaid, both based on novels by Cornell Woolrich. The more successful of the two, both critically and commercially, The Bride Wore Black stars Jeanne Moreau (late of Jules and Jim) as a woman distraught over the murder of her childhood sweetheart on their wedding day who decides to track down the men responsible. As she eliminates them one by one, we learn a little bit more about her motivation until we find out exactly what happened on that fateful day. Then it’s a matter of whether she’ll be able to carry out the rest of her plans before her conscience or the police catch up with her first.

For Mississippi Mermaid, Truffaut had a bigger budget to work with, but the film saw diminishing returns despite extensive location shooting and the presence of stars Jean-Paul Belmondo and Catherine Deneuve. (Even Deneuve’s fleeting topless scenes failed to bring in the crowds.) Belmondo plays a plantation owner based on a small island off the coast of Madagascar who sets his heart on marrying Deneuve after only corresponding with her. Once she arrives, it turns out neither of them was entirely honest with the other – he downplayed his wealth and position and she sent him a bogus picture – but they go ahead with the marriage anyway. Then one day an alarming letter arrives and Deneuve flies the coop with most of Belmondo’s money. His pride wounded, he hires a private detective to find his runaway bride, but then decides to track her down himself.

There are numerous allusions to Hitchcock’s oeuvre throughout the film, with the most obvious antecedent being the similarly flawed Marnie, which also deals with a woman who meets rich men under false pretenses and takes them for everything she can. Curiously enough, the ending of the film echoes one of the rejected endings of Hitchcock’s Suspicion, which Truffaut must have known about. One has to wonder, if it didn’t pass muster for the Master of Suspense, why did he think it would work for him?

Switching gears, Truffaut entered the ’70s with The Wild Child, the first time he gave himself a starring role in one of his films. It tells the true story of a boy who was found running naked in the woods in the south of France in 1798 and how he reacted when he was introduced to civilization. I strongly suspect Truffaut assumed the role of Dr. Jean Itard, a specialist in deaf-mutes who took a personal interest in the case, because he knew he was going to be working closely with the young actor playing the title character (a remarkably feral Jean-Pierre Cargol). Incidentally, by the end of the film the “wild child” has grown considerably more tame, but it’ll still be a while before he reaches Kaspar Hauser levels of social integration.

Jean-Pierre Cargol & Truffaut

●

One decade after reaching the heights of romance with Jules and Jim, Truffaut made Two English Girls, based on another novel by Henri-Pierre Roché. Released in 1971, it stars Jean-Pierre Léaud as a young Frenchman and aspiring writer who travels to Wales to visit with a pair of sisters (Kika Markham and Stacey Tendeter) because their mother is friends with his mother. Of the two of them, older sister Markham is more approachable, but Tendeter is the one who initially captures his fancy, which is only inflamed by her reclusiveness. Even if the given reason for this is perfectly reasonable — she suffers from eye strain and has to rest them for fear of going blind — it still gives her an air of unavailability. Things don’t really get complicated, though, until Léaud gets involved with Markham when she moves to Paris to become a sculptress. Their situation even inspires him to write a book very much like Jules and Jim, which probably seemed like a good idea at the time.

By the time Day for Night picked up Best Foreign Film at the Academy Awards, Truffaut was on the radar of Roger Corman, whose New World Pictures picked up numerous foreign films for distribution in the ’70s. The first of two Truffaut films New World released — 1975’s The Story of Adele H. – even managed to garner an Oscar nomination for its lead actress, Isabelle Adjani, which was something that rarely happened with the company’s home-grown product. Adjani plays the daughter of Victor Hugo (who is called “the most famous man in the world” at one point, which explains why she travels under an assumed name), who travels to Halifax, Nova Scotia, in pursuit of a British officer (future Withnail and I writer/director Bruce Robinson) with whom she is madly in love. Sadly for Adjani, the feeling is not mutual and in her delusion she becomes something of a stalker. It’s a heartbreaking performance that becomes progressively more difficult to watch as she divorces herself further and further from reality. No wonder the Academy was impressed.

No acting nominations resulted from Truffaut’s next film, 1976’s Small Change, but it proved he hadn’t lost his flair for directing children. An episodic slice of life set in the last few weeks of school before the start of summer vacation, it recounts the misadventures of a classroom full of children, focusing on a handful of them as they get in and out of various scrapes. It’s hard to say which scene is more memorable, the one where a precocious toddler falls out a seven-story window and bounces right back as if he had merely tumbled off the couch or the one where a girl gets on a bullhorn to announce to an entire high rise that her parents have locked her in while they go out to eat and she’s hungry. In either scenario, it’s incredible that the parents didn’t have to answer to charges of child neglect.

Scene From “Small Change”

●

The following year, Truffaut went from a film that demonstrated how much he loved children to making The Man Who Loved Women, which begins and ends at the funeral of the title character — whose passing, his editor (Brigitte Fossey) notes, is being mourned exclusively by women — but within that frame it’s bookended by a pair of car accidents that illustrate how little control he has over how he’s affected by the fairer sex. A devout and unapologetic leg man, Charles Denner is introduced faking a hit-and-run just so he can locate a leggy driver whose license plate he managed to scribble down as she drove off. And at the end he’s so distracted by a skirt he’s chasing that he walks right out into traffic and gets hit by a car. Such is the lot of a man called “the wolf with a wearied look” by one of his countless conquests.

As the film progresses, we meet a number of Denner’s beauties after the rejection of one, a middle-aged boutique owner who is only attracted to younger men, sends him to the typewriter to peck out a book all about the women in his life (starting with his mother, who’s briefly glimpsed in black-and-white flashbacks). By far, the one he devotes the most space to is a mercurial married woman (Nelly Borgeaud) who enjoys having sex in public places, which makes their months-long affair a nerve-wracking one. It’s only after he’s completed his manuscript and it’s ready to go to press, though, that he has a chance run-in with a bitter ex (Leslie Caron) that he somehow left out of the book. Fossey won’t hear of him making any last-minute changes and suggests he save her for the follow-up, but his sudden urge to play in traffic prevents him from writing that.

When Truffaut made The Story of Adele H., he eliminated all of the master shots, which allowed him to stretch his budget further and make a smaller film look larger. Three years later, he applied the same principle to 1978’s The Green Room, based on a story by Henry James, which takes place in a small French town in the late ’20s. It’s a little over a decade after the Great War, which Truffaut’s character fought in, and nearly the same amount of time since the death of his young bride, who waited patiently for him all throughout the fighting and then died right after their wedding. Since then, Truffaut has been consumed by her memory and even has a room in his house dedicated to her, but he soon resolves to refurbish an abandoned chapel to make a more permanent memorial to all the people he’s known who have died.

Isabelle Adjani With Truffaut In “The Story Of Adele H.”

●

With its morbid subject matter and emotionally closed-off main character, The Green Room failed to catch on with audiences, but Truffaut turned things around with the following year’s Love on the Run, the capstone of the Antoine Doinel saga. (It’s possible it could have continued if Truffaut hadn’t died so young, but we’ll never know what he had in mind.) Then, after The Last Metro and its story of the German occupation of France during World War II, Truffaut left the past behind for two contemporary films that turned out to be his last.

When romance flames out in a spectacular fashion, are both parties irrevocably burned by the experience or are they capable of rekindling their passion years later? That’s the central question posed by 1981’s The Woman Next Door, in which Gérard Depardieu’s quiet life in a tiny French village is disturbed when ex-lover Fanny Ardant (Truffaut’s partner until his death) moves into the house across the street with her new husband. Depardieu, too, has settled down with a wife (Michèle Baumgartner) and small boy, but neither of their domestic arrangements can erase the undeniable attraction they still feel for each other.

In his defense, Depardieu does try to head things off at the pass by pretending to work late when Baumgartner invites their new neighbors over for dinner, and he steers clear of Ardant as much as he can without raising suspicion, but all it takes is one stolen kiss in a parking garage and it’s only a matter of time before they start meeting in hotels and so forth. From that point on, all of their public interactions are marked by the increasing strain of keeping their affair secret, although local tennis club owner Véronique Silver is wise to it pretty much from the start. That makes sense since she’s the character Truffaut and his co-writers chose to narrate the film. Based on her own experiences, she’s well-versed in the fallout that doomed love affairs are prone to.

Made in 1983 as a lighthearted variation on the Hitchcock-inspired thrillers he turned out in the late ’60s, Truffaut’s swan song Confidentially Yours is about a real-estate agent (Jean-Louis Trintignant) who finds himself in a real pickle when his wife and her lover both turn up dead and the police think he’s their man. Lucky for him, his headstrong secretary (Fanny Ardant again) is ready and willing to do the legwork and try to find out who wanted them dead because the police sure aren’t interested and his lawyer believes he should turn himself in and claim it was a crime of passion.

Fanny Ardant In “Confidentially Yours”

●

Ardant’s investigation takes her to Nice, where she looks into the wife’s past, and gives Truffaut the perfect opportunity to recreate the famous shot from Psycho of Janet Leigh driving in the rain. (This moment alone justifies his decision to shoot the film in black and white.) Hitchcock isn’t the only director on his mind, though, since another plot point revolves around a cinema that’s showing Kubrick’s Paths of Glory. And the voyeur angle is provided by Ardant’s ex-husband (Xavier Saint-Macary), a photographer who always seems to be lurking around. Exasperated as he gets with Ardant, though, Trintignant is fortunate to have somebody who’s so thoroughly on his side — save for those fleeting moments when it crosses her mind that he may be guilty after all.

As breezily entertaining as it is, it’s hard to ignore the feeling that Confidentially Yours is somewhat inconsequential. That wouldn’t be so bad, but around the time of its release Truffaut suffered a stroke and was diagnosed with a brain tumor. He eventually died on October 21, 1984, leaving a number of unfinished projects in the planning stages. I’m sure he would have liked his final film to be a bit weightier, but the body of work he left behind is substantial enough to keep film lovers occupied for a long time to come.