▼

A Provisional List Of The Year’s Best Films by Craig J. Clark

◆

For the third year running, I have been tasked by The Ryder with providing a summary of the year in film. As ever, it’s difficult for me to compile a proper year-end list when there are still so many major films that I haven’t been given the chance to see. Among the ones that didn’t make it to the Bloomington area by press time are the Coen Brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis, David O. Russell’s American Hustle, Spike Jonze’s Her, Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street, Asghar Farhadi’s The Past, and Hayao Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises. Even after removing those from the equation, though, there are still plenty of great films left for me to pull together a baker’s dozen that are worth seeking out, either at home or (in some cases) still in theaters.

One thing that hung over the first half of the year, cinematically speaking, was Steven Soderbergh’s impending retirement from film directing. If he sticks to it, that would make his last domestic release Side Effects, a solid medical thriller in the same way Haywire was a solid actioner and Contagion was a solid disaster film. Side Effects was merely a warm-up, though, for his true swan song Behind the Candelabra, which premiered on HBO in the States, but actually screened in competition at the Cannes Film Festival and has been shown in theaters virtually everywhere else in the world but here. Anchored by Michael Douglas’s flamboyant performance as Liberace – one that extends beyond mere impersonation and finds the beating heart beneath all the sequins and razzle-dazzle – and Matt Damon’s take on hunky up-and-comer Scott Thorson, who finds himself caught in the glitzy showman’s orbit, Behind the Candelabra is a compelling portrait of a closeted entertainer and his overwhelming need to see himself reflected in the beaming faces of his (invariably) younger lovers.

“Frances Ha”

■

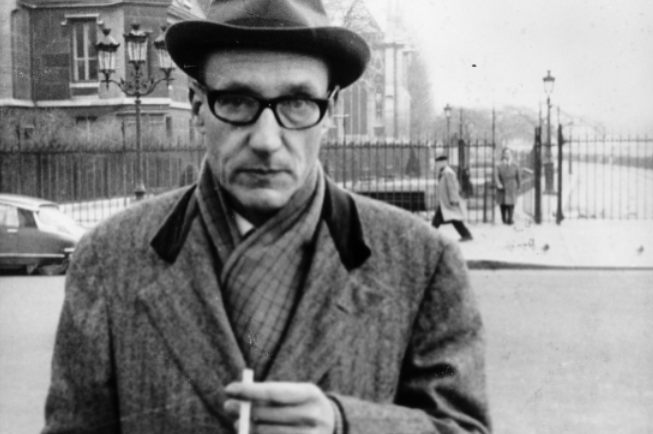

Summer brought with it the usual conflagration of big-budgeted blockbusters and star-driven spectacles, but I was more taken with the intimate character studies of Frances Ha and Before Midnight. Filmed on the streets of New York in luminous black-and-white, Frances Ha is an unabashed love letter to the city and to its lead actress, Greta Gerwig, who co-wrote the screenplay with director Noah Baumbach. As an understudy for a cash-strapped modern-dance troupe who is struggling to hold onto her dream of dancing professionally, Gerwig’s Frances has a lot of growing up to do over the course of the film, which is why it’s so gratifying when she finally comes into her own.

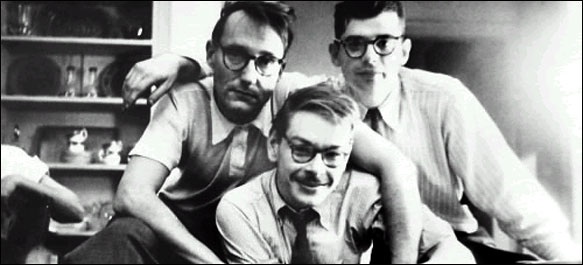

While Frances is trying to find her place in the world, Céline and Jesse, the protagonists of Before Midnight, have settled into an uneasy partnership that threatens to dissolve during an evening of no-holds-barred self-examination. Returning to the characters they previously played in 1995’s Before Sunrise and 2004’s Before Sunset, Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke continue to compel us to care about them as a couple, raising the stakes in a way that feels organic to the story, which they once again concocted with director Richard Linklater. If they plan on keeping to this schedule, I look forward to seeing where the two of them are in another nine years.

“Before Midnight”

■

The closest analogue to the Before trilogy is Michael Apted’s Up series, which has been checking in with the same group of Britons every seven years, starting when they were seven years old in 1964’s Seven Up! Over the years, some of the participants have dropped out and then dropped back in again, but 13 of them made themselves available to Apted’s camera crew when it came time to make 56 Up. (As is sometimes the case, one who’s been absent since 28 Up returned mostly to garner some free publicity for his band.) Taken individually, the Up films may not seem that revelatory, but their true power lies in the accumulation of detail as each installment builds on the ones that came before it. And I’m not ashamed to admit that the way each one ends with a replay of the closing moments of Seven Up! never fails to bring me to tears.

The capacity of human beings to be moved by the plights of strangers (or not, as the case may be) is at the heart of Joshua Oppenheimer’s documentary The Act of Killing, which examines the fallout from Indonesia’s anti-Communist purge following the military’s 1965 coup. Cannily, Oppenheimer does this by telling the story of Anwar Congo, a gangster-turned-executioner who’s more than happy to demonstrate his wire-strangling technique for his camera. “This is how to do it without too much blood,” he boasts, but when he’s shown the footage later on he’s not impressed because it doesn’t look realistic enough. When Congo’s given the chance to do some re-enactments with the help of actors, makeup artists and the like, though, he starts to recognize just where his bad dreams come from. The result isn’t always a pretty sight, no matter how baroque some of Congo’s fantasies are, but the birth of a conscience is a rare thing to capture on film.

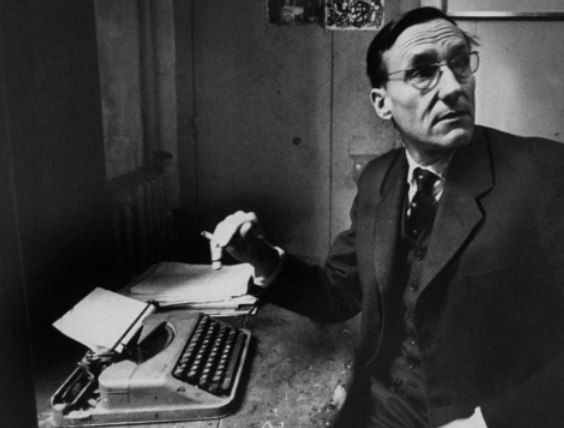

Another rarity in the world of film is the work of multi-hyphenate Shane Carruth, who went nine years between his debut, 2004’s Primer, and his follow-up, this year’s Upstream Color. Like Primer, Upstream Color is designed to be the sort of film that one needs to see more than once in order to fully grasp everything that’s going on, but it can also be appreciated for its hazy, dreamlike atmosphere. This is a quality shared by Peter Strickland’s Berberian Sound Studio, which stars Toby Jones as a soft-spoken British sound engineer who’s summoned to Italy to supervise the mix on what he’s dismayed to learn is a horror film. On top of that, the longer he works on “Il Vortice Equestre” (or “The Equestrian Vortex,” which doesn’t have all that much to do with horses), the less Jones is capable of distinguishing between it and reality, leading to a break in the film that matches his mental state. I guess seeing yourself dubbed into Italian can have that effect if you’re not prepared for it.

“Upstream Color”

■

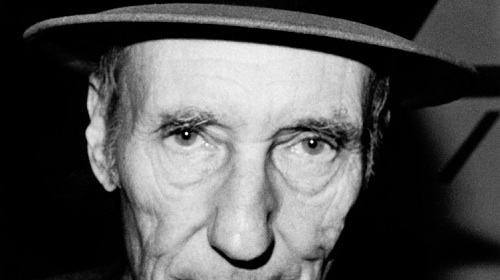

While the protagonists in Upstream Color and Berberian Sound Studio have a difficult time adjusting to the circumstances they find themselves thrust into, the dangers of living in the past are ever-present in Edgar Wright’s The World’s End, in which his co-writer Simon Pegg gets his old mates back together 23 years after they failed to complete The Golden Mile, a twelve-pub crawl in their hometown. In the years since, his mates (whose ranks include uptight real estate agent Martin Freeman, soulful property developer Paddy Considine, weedy car salesman Eddie Marsan, and teetotaling corporate lawyer Nick Frost) have managed to grow up and become productive members of society, so they’re reluctant to give it another go, but as the oft-repeated refrain goes, there’s no point in arguing with Pegg. The perfect film for anybody who enjoyed the first two parts of the Cornetto Trilogy (Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz), The World’s End also pulls off its “end of the world” scenario with a lot more heart than Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg’s similarly apocalyptic This Is the End, which has its moments, but was less interested in combining them into a satisfying whole.

“The World’s End”

■

One of the nastiest surprises of the summer came right at the end of it with the belated release of You’re Next, a well-plotted home-invasion horror film that had the misfortune to come out a few months after The Purge (which should have been purged from multiplexes). Unlike a lot of its impatient ilk, You’re Next eases the audience into its milieu, introducing us to the potential victims and their attendant quirks before a trio of thugs in animal masks descend upon them with an array of sharp weaponry at the ready, prepared to pick them off one by one. Once the games get underway, we discover just how thorough the hunters are — nobody can get a signal, their cars have been disabled, the power is cut — and how surprisingly resourceful one of the would-be victims is in an emergency. Director Adam Wingard and screenwriter Simon Barrett keep the surprises coming, though, making it impossible to predict who’s going to be next or how they’re going to get it.

The last four films on my list are all recent enough releases — and are garnering enough attention from various critics groups — that I probably don’t need to go into too much detail about them. Interestingly, three are about how individuals hold up when they’re dealt an unlucky hand. J.C. Chandor’s All Is Lost is a compelling tale of survival starring Robert Redford as a highly resourceful yachtsman whose boat is damaged beyond repair in the middle of the ocean, but in the gritty-determination department he’s matched by Sandra Bullock and George Clooney as astronauts set adrift in orbit after their ship is struck by space debris in Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity. They’re all trumped, though, by Chiwetel Ejiofor as the wrongfully enslaved freeman in the pre-Civil War South who goes from one untenable situation to the next in Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave. In comparison, Bruce Dern’s borderline-senile would-be sweepstakes winner in Alexander Payne’s Nebraska doesn’t have it so bad, now does he?

◆

Craig J. Clark’s Top 13 of 2013 (listed alphabetically)

- The Act of Killing

- All Is Lost

- Before Midnight

- Behind the Candelabra

- Berberian Sound Studio

- 56 Up

- Frances Ha

- Gravity

- Nebraska

- 12 Years a Slave

- Upstream Color

- The World’s End

- You’re Next