▼

All the World’s on Stage ◆ by Paul Sturm & LuAnne Holladay

The 20th Lotus World Music and Arts Festival will fill the venues and streets of Bloomington from September 25-29. Lotus at 20 means brilliant musical performances, inspiring and engaging visuals, a Saturday night parade, family-friendly arts in the park, and an exuberant street scene. The Festival includes ticketed showcase performances on Friday and Saturday nights, plus free events including a concert at IU, the annual Arts Village on 6th Street, and the popular Lotus in the Park concerts and workshops on Saturday afternoon at 3rd Street Park. Admission to Sunday’s annual World Spirit Concert is the $5 Lotus Pin for 2013, based on art from the first Festival in 1994. (Purchases of the collectible pin support Lotus’s free programming.) Artist Karen Combs designed both the original 1994 Lotus art and this year’s signature design.

This anniversary shindig wouldn’t be complete without special hoopla apropos to 20 years. Lotus at 20 is obliging with three concert events leading into the weekend fête. It begins with an African Showcase concert on Wednesday, 9/25 at the Buskirk-Chumley Theater (BCT), featuring Bassekou Kouyate & Ngoni Ba, and Noura Mint Seymali. Two concerts are scheduled for Thursday, 9/26: the traditional opening concert at the BCT, this year featuring Monkey Puzzle and Frigg; and a free-admission Lotus+IU Campus Concert at Alumni Hall in the Indiana Memorial Union, featuring Pan-Basso, Funkadesi, and Nomadic Massive.

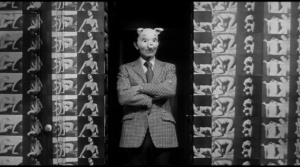

Part of the Lotus at 20 celebration is the Power of Pattern arts outreach project, which created a new backdrop for the BCT stage. Designs for the backdrop were selected from more than 400 submissions from across the community. Members of the public will be able to see the backdrop up close at a free pre-concert reception on Wednesday at the BCT. And the Ivy Tech John Waldron Arts Center Galleries once again devote exhibit space to a Lotus-related exhibition: World Blues: Shades of Indigo on view September 6-28, free and open to the public.

Venues involved in Lotus at 20 include:

See the online venue map and official events schedule.

The Lotus at 20 roster of performing artists tops 30. The list includes a handful of returning favorites, a strong Nordic contingent, some fine West African musicians, adventurous folk fusion from Central and Eastern Asia, hip-hop from Montreal, bhangra brass from Brooklyn, exquisite vocal music, magnificent Indian classical music, and some great Bloomington-based bands.

◆

Artist Profiles & Performances

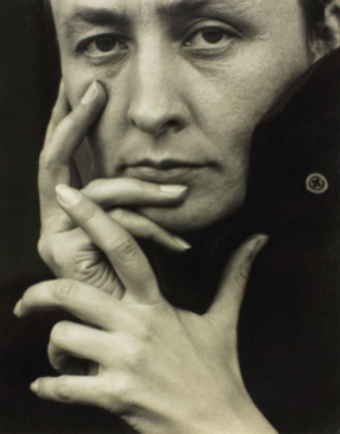

■ Amjad Ali Khan with Amaan Ali Khan & Ayaan Ali Khan India

Amjad Ali Khan is a master of the sarod, a lutelike instrument important in Indian classical music traditions. A sixth-generation sarod player (his sons are the seventh generation of Khans to play), Amjad Ali Khan is part of a long line of makers and players. He says, “You could say it’s my family instrument; whoever is playing the sarod today learned directly or indirectly from my forefathers.” Although he has collaborated with musicians from other artistic and cultural traditions — most notably for Lotus audiences, singer-songwriter Carrie Newcomer — Khan focuses on classical Indian music, which includes ragas. To best appreciate the Khans’ performance, sit and stay awhile, and get lost in the artistry.

- One show only: Saturday, September 28, 7-8:15pm, BCT

◆

■ Arga Bileg Mongolia

The seven-piece group Arga Bileg introduces jazz improvisation into Mongolian folk music traditions. The ensemble includes polished musicians, composers, and choreographers; their sound is elegant and compelling. Traditional Mongolian music is strongly influenced by nature, nomadism, shamanism. Arga Bileg combines these influences with contemporary Western jazz techniques, creating a unique combination of East and West, and keeping their native musical tradition lively and inventive.

- Friday, September 27, 7-8:15pm, BCT

- Saturday, September 28, 12:15-1pm; free, 3rd Street Park

- Saturday, September 28, 10:30-11:15pm, BCT

◆

■ Barbara Furtuna Corsica

This brilliant vocal quartet — one of the most-requested Lotus artists — makes its second Lotus appearance at the 20th Festival. Steeped in the ancient vocal practice of Corsican polyphony, Barbara Furtuna perform a repertoire of classic songs from sacred tradition as well as those of their own making. Their soulful, intricate interweaving of harmonies is a soaring vocal experience not to be missed.

- Saturday, September 28, 8:45-10pm, FUMC

- Sunday, 9/29, 4-5pm, BCT

◆

■ Bassekou Kouyate & Ngoni Ba Mali

Malian musician Bassekou Kouyate is a master of the traditional West African spiked lute, or ngoni. His eight-piece ensemble, Ngoni Ba, combines the energy of a rock band with the soulful call-and-response dynamism of a gospel group. “A virtuoso picker and musical visionary whose work blurs the lines between West African and American roots music, Bassekou has jammed with Bonnie Raitt and Bono, and won praise from Eric Clapton…” (Subpop). He recorded his recent album, Jama Ko (translated: “big gathering of people”), during a military coup in Bamako. Like many other Malian musicians in the recent past, his music is a call for peace and unity for the people of his country.

- Wednesday, September 25, 7-9pm, BCT

- Friday, September 27, 8:45-10pm, ION Tent

◆

■ Christine Salem France: Réunion Island

Christine Salem sings maloya (traditionally sung by men), the African-influenced music of the Creole descendants of slaves who once worked the sugar plantation of Réunion Island, in the Indian Ocean. With powerful percussion — which Salem also plays — and call-and-response singing, maloya was used in ceremonies that brought participants into trancelike states in which they hoped to speak to ancestors. Although Salem doesn’t perform the same trance music on stage, she draws strongly on its forms. Maloya was long banned by French secular and religious authorities on the island; the ban was only lifted in 1981. “They thought trance music was the devil’s song,” Salem says “but it’s great music.”

- Friday, September 27, 7-8:15pm, ION Tent

- Saturday, September 28, 8:45pm-10pm, ION Tent

◆

■ DakhaBrakha Ukraine

DakhaBrakha comes from Kyiv, Ukraine, and the quartet’s name means “give/take” in the old Ukrainian language. Their sound is anything but old, however. Reworking their native folk music and song with Indian, Arabic, Russian, Australian, and African instruments, the band’s music is built on a foundation of distinctive, powerful vocals. They began at Dakh Theatre for Contemporary Arts in Kyiv, and they have always taken an avant-garde approach to tradition, experimenting with the structures and order of folk music, and introducing experimentation and improvisation. “This is a phenomenal Ukrainian outfit, mixing genuine, ethnically specific material with minimalist jazz and the precision of techno-beats; they’re making the natural folk music of the future” (fRoots). DakhaBrakha’s compelling music will linger long in memory; it’s a must-see premiere for Lotus at 20.

- Friday, September 27, 10:30-11:45pm, ION Tent

- Saturday, September 28, 10:3o-11:45pm, ION Tent

◆

■ David Wax Museum USA: Boston

The David Wax Museum’s eclectic sound has roots in Mexican and American cultures. David Wax has immersed himself in Mexico’s rich traditional music, learning son styles from the form’s living masters. Suz Slezak was reared on American roots music in Virginia — old time, Irish, classical, and folk. The two met in 2007 and began blending their unique musical perspectives — Mexican folk and American roots — with indie rock. As a gringo spin on real-deal Mex-rock like Café Tacuba or Zoé, David Wax Museum is pretty fly for dos estadounidenses. Their sonic mestizo is perfect for the Lotus cultural gumbo.

- Friday, September 27, 8:45-10pm, FPC

- Saturday, September 28, 7-8:15pm, ION Tent

◆

■ De Temps Antan Canada: Quebec

De Temps Antan — the trio of Éric Beaudry (vocals, guitar, mandolin, bouzouki), André Brunet (vocals, fiddle), and Pierre-Luc Dupuis (vocals, accordions) — has been exploring and performing traditional Quebecois songs and instrumental music for more than a decade, and they’ve each played the music for most of their lives. Their wicked good playing and joyous harmonies embody the energy and joie de vivre of Quebec’s “kitchen music” tradition. After a crowd-pleasing performance at the 2009 summer Lotus concert, De Temps Antan returns for Lotus at 20.

- Friday, September 27, 10:30-11:45pm, FPC

- Saturday, September 28, 2:30-3:15pm, free, 3rd Street park

- Saturday, September 28, 10:30-11:15pm, The Bluebird (21 and older)

◆

■ Debo Band Ethiopia & USA: Boston

The 11-member Debo Band is led by Ethiopian-American saxophonist Danny Mekonnen, and fronted by vocalist Bruck Tesfaye. Since their inception in 2006, Debo Band has won raves for their groundbreaking take on Ethiopian pop music, which incorporates traditional Ethiopian scales and vocal styles, American soul and funk rhythms, and instrumentation reminiscent of Eastern European brass bands. National Public Radio’s All Songs Considered reviewers frothed, “They play [Ethiopian pop] without any sort of… precious reverence… they play it like it’s NOW, as music of right now, and they play it with incredible energy and passion and excellence; and it just totally rocks; it’s amazing.” Another barnstorming global party band to keep our Lotus at 20 tent peeps mad-dancing.

- Friday September 27, 7-8:15pm, Soma Tent

- Saturday, September 28, 7-8:15pm, Soma Tent

◆

■ Edmar Castaneda & Andrea Tierra Colombia

Bogota-born Edmar Castaneda is a master of the arpa llanera, or Colombian folk harp. Castaneda’s skill and talent on his instrument is truly virtuosic. He plays with vigor, precision, and the improvisational flair of a jazz master. Castaneda is joined onstage by his wife, jazz vocalist and poet, Andrea Tierra; together, they deliver thrilling and memorable sets. “Producing cross-rhythms like a drummer; smashing chordal flourishes like a flamenco guitarist; collating bebop and Columbian music; he’s almost a world unto himself” (NY Times). Castaneda’s performances are like nothing else in contemporary folk music.

- Two Shows, One Night Only: Saturday, September 28, 7:30-8:15pm & 10:30-11:15pm, FCC

◆

■ Frigg Finland

Frigg is at the forefront of a new generation of musicians using the deep folk traditions of Norway and Finland as a launching pad for new, fresh string music. With a bank of four fiddles, upright bass, guitar, and mandolin, Frigg plays some of the most exciting music you’ll ever hear: a lyrical, often break-neck style they call “Nordgrass” (blending Nordic fiddle styles and American bluegrass). When they first came to Lotus in 2004, they were relatively new on the Nordic string scene. Nearly 10 years later, they tour the world all the time, and they’ve made lots of friends and fans in Bloomington. Traditional music on acoustic instruments — but supercharged; the Frigg sound is powerful, exhilarating, and perfect for our Lotus at 20 celebration.

- Thursday, September 26, 7-9pm, BCT

- Friday, September 27, 8:45-10pm, BCT

◆

■ Funkadesi USA: Chicago

The funky and irresistible sonic mix of Funkadesi comes from the diverse cultural and musical backgrounds of its members, who first came together almost 20 years ago to work Indian improvisations over reggae and funk grooves. They’ve won six Chicago Music Awards since then. A Funkadesi set is a non-stop musical excursion traveling from reggae, to bhangra and Bollywood, to Latin American rhythms and rump-bumping grooves, to territories beyond (and bodacious). The musicianship is tight and dense, with loads of percussion, bass, guitar, sitar, keyboards, flute, sax, and vibes. The vocals are exhilarating. Funkadesi takes great pride in being a Lotus mainstay — they’re the second-most frequently-booked Lotus band, and this year marks their seventh appearance at the Festival. Lotus at 20 gives up the funk with our second city soul brothers: Funkadesi time is always par-tay time.

- Thursday, September 27, 8-10:30pm, free, Alumni Hall

- Friday, September 28, 10:30-11:45pm, Soma Tent

◆

■ Janusz Prusinowski Trio Poland

Making their Lotus debut, the Janusz Prusinowski Trio (actually larger than a trio) plays traditional village music from central Poland; but they also work elements of that musical tradition into new treatments. The mazurkas that are the heart of much Polish village music — a musical style that has been sung, played to, danced to, and improvised on since the sixteenth century — take on new life with JPT. “These guys play with high skill and all the fire and rhythmic energy of the village musicians they’ve learned from” (fRoots).

- Friday, September 27, 8:45-10pm, FUMC

- Saturday, September 28, 4-5pm, free, 3rd Street Park

- Saturday, September 28, 10:30-11:15pm, FUMC

◆

■ Japonize Elephants USA: Bloomington

A Japonize Elephants performance is a magical experience. The Elephants have been experimenting and collaborating for 20 years, beginning as a local B’ton band. They’re a “wild, Appalachia-by-way-of-the-Middle East hyper-speed gypsy caravan that’s as baffling as it is inspiring and hilarious” (Secretly Canadian). Their adventurous, tremendously appealing music sounds mysterious, rollicking, and vaguely familiar to the casual listener. But for the audiophile, the Elephants’ influences are clear: Frank Zappa, Ralph Stanley, film scores, jazz, Eastern flavors, country, space pop, and more. “Listening to Japonize Elephants is like being at a supersonic hillbilly hoedown that has been mysteriously transplanted into a Transylvanian cartoon” (Denver Post). They started here in B-town, and they’re back for Lotus No. 20.

- One Show Only: Saturday, September 28, 8:45-10pm; The Bluebird (21 and over)

◆

■ Jefferson Street Parade Band USA: Bloomington

The Jefferson Street Parade Band is a Bloomington original, part of the renaissance that has given brass and marching bands new life in the last decade. They draw on songs and rhythms from West Africa, New Orleans, Eastern Europe, and Latin America: drums, brass, and even electric bass (thanks to a battery-backpack rig). This summer, they led the Lotus Fest contingent in our 4th of July Parade (and won best musical entry for their efforts). Every day is a parade, every parade is a party, when JSPB leads the way.

- Two Shows, One Night Only: Saturday, September 28, 7-8:15pm; Bluebird (21 and over) & 8:15-8:45pm, free, Lotus Parade

◆

■ Kardemimmit Finland

The four young women of Kardemimmit are all singers, and all play the Finnish national instrument: the kantele. They perform traditional Finnish songs as well as their own modern, original folk music — adding to a long and dynamic musical tradition. If you’re new to the kantele, think zither or dulcimer; the quartet play both the 15-stringed and 38-stringed varieties. The distinctive sound of this plucked acoustic instrument, combined with their assured yet delicate vocal harmonies, makes Kardemimmit a stand-out contemporary Nordic ensemble. With Frigg, they give the 20th Lotus Fest its strongest Finnish flavor ever.

- Friday, September 27, 10:30-11:45pm, FUMC

- Saturday, September 28, 3:15-4pm, free, 3rd Street Park

- Saturday, September 28, 6:30-7:15pm, FCC

- Sunday, September 29, 3-4pm; BCT

◆

■ Leyla McCalla USA: New Orleans

Leyla McCalla, the daughter of Haitian emigrants, studied cello at NYU, and moved to New Orleans, where she fell in love with Creole music and culture, spent time busking, and eventually played with the Carolina Chocolate Drops. A multi-instrumentalist as well as a singer, McCalla will soon release a CD that reflects her “personal exploration of African-American and Haitian history through song” — songs written to poetry of Langston Hughes, Haitian folk songs, and original work. Lotus at 20 marks McCalla’s debut in B-town.

- One Show Only: Saturday, September 28, 8:45-10pm, FCC

◆

■ Lily & Madeleine USA: Indianapolis

Teen-aged sisters Lily and Madeleine Jurkiewicz became a YouTube sensation when their first original song, In the Middle, generated more than a quarter million views (their first CD is set to be released in October). Their sweet, poignant harmonies transform covers into songs seemingly from another time, and their original songs have a timeless feel, too. They’ve been featured on Vogue.com and NPR Music, and they’ve recorded a song with fellow-Hoosier John Mellencamp. Their star is on the rise. Lily is a student at IU, and Madeleine is still in high school, but somehow they find time to tour sold-out shows. Come see what the buzz is about.

- Two Shows, One Night Only: Saturday, September 28, 6:30-7:15pm & 7:30pm-8:15pm, FPC

◆

■ Liz Carroll & Jake Charron USA: Chicago

In 1975, when she was only 18, Liz Carroll won the All-Ireland Senior Fiddle Championship. In 2011 she was awarded the Cumadóir TG4, Ireland’s most significant traditional music prize. Carroll is one of few Americans to capture these prizes of Celtic traditional music. She plays old Irish tunes as well as her own compositions, and she has done much to keep Irish fiddle traditions lively and evolving. That work was recognized on this side of the Atlantic with a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. Carroll is revered as one of Irish America’s premier musicians, a fitting treat for Lotus at 20 audiences. Carroll will be accompanied by Canadian musician, Jake Charron, on guitar and piano.

- One Show Only: Saturday, September 28, 7-8:15pm, FUMC

◆

■ Lotus Dickey Song Workshop USA: Bloomington

Grey Larsen, Janne Henshaw, and Mark Fedderson — all of whom knew Hoosier musician and songwriter Lotus Dickey (1911-1989) — will lead a workshop where you can learn some of his best songs. The Lotus World Music and Arts Festival was named in part for Lotus Dickey, whose humble, gentle, creative spirit inspired the festival and its mission. The workshop is an occasion to celebrate Dickey’s contribution to the art and life of Indiana, and to enjoy the power of voices united in song.

- One Show Only: Saturday, September 28, 1:45-2:30pm, free, 3rd Street Park

◆

■ Monkey Puzzle USA: Bloomington

Monkey Puzzle was part of Bloomington’s a cappella scene in the 1990s, sporting a repertoire that spanned African folk music to American pop covers. The group dispersed and moved on from B-town, but Lotus hosted two reunion concerts in the early 2000s. For Lotus at 20, MP members Nils Fredland, Nicole Kousaleos, Jerry McIlvain, Daniel Reed, and Dan Schumacher are reuniting again for an encore performance.

- One Show Only: Thursday, September 26, 7-9pm, BCT

◆

■ Mr. Taylor and His Dirty Dixie Band USA: Bloomington

Mr. Taylor and His Dirty Dixie Band is homegrown hipness; all of the members are students in the IU Jacobs School of Music. They play delicious Dixieland jazz, traditional style (think New Orleans, early 1900s); with Benjamin Taylor on trumpet, Justin Knapp on clarinet, Victor Ribadeneyra on trombone, Otis Cantrell on guitar and banjo, Douglas Olenik on tuba, and Bridget Leahy on drums.

- Two Shows, One Day Only: Saturday, September 27, 1-1:45pm, free, 3rd Street Park & 8:15-8:45pm, free, Lotus Parade

◆

■ Nomadic Massive Canada: Quebec

The cultural landscape of Nomadic Massive is Argentinian, French, Algerian, Haitian, Chilean, Barbadian, Grenadan — it reflects Canada’s amazing ethnic diversity. These nine independent artists describe themselves as “musical nomads.” They rap socially aware poetry in English, French, Creole, Spanish, and Arabic, and combine live instrumentation with electronic sampling. This Montreal-based collective makes its Lotus debut, bringing dynamic, funky, high-energy “pass the mic” throwdown sounds to our Lotus party tent scene. Bust a global rhyme, word nerds; mosh hard, millennial gypsies!

- Thursday, September 26, 8-10:30pm, free, Alumni Hall

- Friday, September 27, 8:45-10pm, Soma Tent

- Saturday, September 28, 8:45-10pm, Soma Tent

◆

■ Noura Mint Seymali Mauritania

Mauritania’s Noura Mint Seymali performs a blend of Afro-pop and desert blues that draws on deep traditional roots and reflects the fusion of Arab and African cultures inherent in Mauritanian life. Her ensemble has traditional instruments at its core — ardine (harp), tidinit (lute), and t’beul (bowl drum) — with Western bass and drum kit to round out the sound. In her home country, the style is called trade-moderne. In Bloomington, we call her music perfectly Lotastic.

- One Show Only: Wednesday, September 25, 7-9pm, BCT

◆

■ Pacific Curls New Zealand

Pacific Curls (Kim Halliday, Ora Barlow, Jessie Hindin) fuse Scottish folk fiddle, traditional Pacific Islands instruments, and songs in Maori and English to create “a delicate balance of shade, weight, propulsion, and introspection” (Womad.org). Pacific Curls performs truly “world” music, swinging from familiar Celtic tunes to more contemporary fusions with island beats and jazz-inflected, multilingual vocals. They’re among the new, exotic voices gracing Lotus at 20.

- Friday, September 27, 6:30-7:15pm, FPC

- Friday, September 27, 7:30-8:15pm, FPC

- Saturday, September 28, 10:30-11:45pm, FPC

◆

■ Pan-Basso USA: Bloomington

Local band Pan-Basso has been tapped to kick-start the IU+Lotus Campus Concert at Alumni Hall in the Indiana Memorial Union. Their high energy playbook of great tunes will get this free-admission dance-fest moving.

- One Show Only: Thursday, September 26, 8-10:30pm, free, Alumni Hall

◆

■ Red Baraat USA: Brooklyn

Brooklyn-based Red Baraat took Lotus by storm when they first played the Festival in 2010, and we’ve been trying to get them back ever since. Founded by dhol-player and band MC, Sunny Jain, this band mixes hard-driving North Indian bhangra beats with jazz, hip-hop, and phat brass funk to bring the party of parties. Red Baraat recordings are amazing; Red Baraat live shows are phenomenal and soul-stirring: a sweat-fest dance frenzy, regardless of your age. Don’t fight the funk, Lo-people; RB jams monster beats with mad energy. “A fiery blend of raucous Indian bhangra and funky New Orleans brass; the result is completely riotous” (Village Voice).

- One Show Only: Saturday, September 28, 10:30-11:45pm, Soma Tent

◆

■ Roberto Fonseca Cuba

Havana-born pianist and composer Roberto Fonseca is known throughout the world for his remarkable music. Jazz, R&B, and the Latin and African rhythms of Cuba come together in Fonseca’s performances. Fonseca’s music is dance-jazz fusion: strong beats supporting melodic ballad lines played with pristine clarity “like a Cuban Keith Jarrett, [diving] into a perpetual-motion ostinato to carry bluesy lines and modern-jazz clusters” (NY Times). He transforms the sounds of Cuban culture into club music for jazzers. Lotus at 20 is thrilled to host Fonseca’s premiere appearance in out town.

- One Show Only: Friday, September 27, 10:30-11:45pm, BCT

◆

■ Sonia M’Barek Tunisia

Tunisian singer Sonia M’Barek is known worldwide for her exquisite renderings of maluf, Tunisian court music traditionally performed by men. She also dips into her own variations on popular music from Egypt and Lebanon, and other musical genres rooted in the centuries-old traditions of Al-Andalus (that part of the Iberian Peninsula governed by Muslims for more than seven centuries prior to the time of Columbus). “Once you know the grammar and understand the tenets of a musical language, you can open to other traditions like Western classical or jazz,” M’Barek says. “Music becomes a way of speaking to other traditions, not only those in the Arab world, but in the West as well.”

- One Show Only: Friday, September 27, 8:45-10pm, FCC

◆

■ Srinivas Krishnan, Abbos Kosimov, Homayun Sakhi, and Friends India, Afghanistan, & Pakistan

No musician has appeared more at Lotus Festivals than percussionist Srinivas Krishnan, who plays the tabla, ghatam, mridangam, dumbek, and bodhran, and is known for bringing diverse world music ensembles together on Lotus stages. This year, he is joined by Uzbek percussionist Abbos Kosimov on the doyra (a frame drum, with jingles, that is common to Central Asia music) and Afghan musician Homayun Sakhi on the rubab (a double-chambered plucked lute with origins in Afghanistan and Pakistan). With special guests, percussionist Jamey Haddad and violinist Dr. M. Lalitha, “Srini” is always a festival fave and his performances are consistently sublime and memorable.

- One Show Only: Friday, September 27, 10:30-11:45pm, FCC

◆

■ The Once Canada: Newfoundland

Perfect vocal harmonies and uncomplicated, elegant acoustic melodies are the hallmark of The Once, a band whose name is a Newfoundland phrase that means “imminently.” Tapping into traditional music, they also perform original songs and even do a cover or two (see what they do to Queen’s You’re My Best Friend). By turns melancholy, funny, and soulful, this trio relies on the power of their voices and acoustic instruments. Featuring singer Geraldine Hollett, with Phil Churchill and Andrew Dale on guitar, mandolin, fiddle, banjo, bazouki, and vocals, The Once has a gentle, commanding presence on stage and in your heart.

- Friday, September 27, 6:30-7:15pm, FCC

- Friday, September 27, 7:30-8:15pm, FCC

- Saturday, September 28, 8:45-10pm, FPC

◆

■ Väsen Sweden

Väsen is three Swedish guys — Olov Johansson on nyckelharpa, Mikael Marin on viola, and Roger Tallroth on guitar — who play beautiful, muscular, exhilarating string music. While Marin’s viola weaves around Johansson’s nyckelharpa line, Tallroth’s driving guitar adds a solid base to the other strings. Theirs is the sound of a living folk tradition. Bloomington likes Väsen so much that we named a street after them (temporarily). Lotus staffers love Väsen so much they’ve twice created “teams” to underwrite their appearances. It couldn’t be Lotus at 20 without Väsen to complete the party. “The sound may be traditional, but the attitude is completely modern, mixing up the ideas of folk, the virtuosity of prog, and the humor of the insane asylum into a Cuisinart of acoustic bliss; visualize whirled music” (Wired).

- Friday, September 27, 7-8:15pm, FUMC

- Saturday, September 28, 8:45-10pm, BCT

◆

Lotus Festival tickets for all admission-based events can be purchased in person at the Buskirk-Chumley Theater Box Office and at Bloomingfoods locations, by phone at 812-323-3020, or online.

The Ryder ◆ September 2013