Could Ireland’s Greatest Tragedy have been prevented? ◆ by Brandon Cook

In 1996, almost 150 years after it occurred, Tony Blair issued the first apology on behalf of the British authorities for the part they played in Ireland’s Great Famine. “That one million people should have died in what was then part of the richest and most powerful nation in the world is something that still causes pain as we reflect on it today,” the prime minister said.

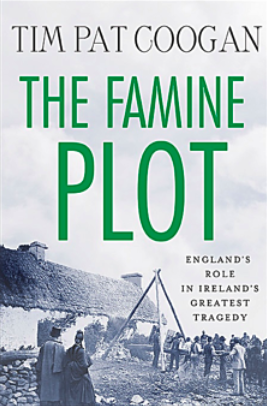

Nowhere does one feel this pain more acutely then within the pages of Tim Pat Coogan’s most recent history The Famine Plot, which sets forth to describe “honestly, without either malice or cap touching, how [Irish] forbears died.”

■

It’s no surprise that the famed Irish historian has at last settled himself upon the Blight as his next subject. His 2001 book Wherever Green is Worn: The Story of the Irish Diaspora contains early seeds of Coogan’s interest—it is probable that the diaspora itself would not exist if the famine had not displaced so many of Ireland’s natives.

But the tragedy, Coogan writes in The Famine Plot, has heretofore been treated with a “strange reluctance” by historians who seem either to subscribe to A.J.P. Taylor’s declaration that “all Ireland was a Belsen,” or else defer from chronicling the grimmer details of the Famine and, in so doing, embrace what the historian Cecil Woodham-Smith called a “colonial cringe” mentality.

Coogan’s book, a pastiche of scintillating research, theory, and vitriol, contains more of the former class than the latter, and yet the author is careful to try and play fair and objective. Like any good historian, he endeavors to let the facts speak for themselves.

For many readers, Ireland’s colorful and in many ways tragic early history will be more or less unknown. To these readers Coogan pays special attention in characterizing the struggles of the 18th century Irish natives, most of which were paupers, as a perennial uphill battle against British imperialism. Like the Americans just 25 years before, the Irish rebelled against their oppressive authorities in 1798, under the flagship of the incomparable Theobald Wolfe Tone. What resulted was not only calamitous for the Irish population (Coogan estimates that 30,000 were “shot down or blown like chaff”) but also for its leadership. Cheating the hangman’s noose, Wolfe Tone committed suicide before he was sentenced to execution. His death would prove to be a haunting precursor to Ireland’s future history of crippled, sovereign heroes (notably, Charles Parnell in 1890 and Michael Collins in 1922).

Great Britain responded to the 1798 Rebellion by extracting all organizational power from the nation that it could, causing a future “leadership deficit” whose harmful implications would be realized during the Famine when it was already much too late. Countrymen, flocking to relief efforts, would find only sporadic benefactors (namely, Quakers) and the clergy, whose circumstances were little better than the countrymen’s. This, combined with a sense of “backyardism,” (England’s belief that it could dictate the goings-on of its neighboring country) would later lead to legislative conflicts, external and internal.

For Ireland’s part, its citizens, particularly its peasantry, reacted to the British ruling with a psychological state known as “learned helplessness.” Cognizant and yet paralytic to their thralldom, their state was characterized by demoralization, a sense of primitivism, and a very real inability to advance their social status. People stayed where they were, inherited their ancestor’s land and their Catholicism, married young, and had children to alleviate their boredom. The effects resultant of “learned helplessness” can still be seen today. Irish citizens, particularly those in the west where the Famine hit hardest, suffer from some of the highest rates of schizophrenia and alcoholism in the world.

It is under this backdrop that Coogan’s “main players” finally enter onto the stage. There are five although only two really matter: the acting prime minister during the first year of the Famine: Sir Robert Peel and the infamous secretary to the Treasury: Sir Charles Trevelyan.

Peel is the only one who earns much sympathy. While his leadership during the Famine did not garner near enough resources to prevent calamity, his main battle was fought against a perverted English ideology of Laissez-faire. A quote from Adam Smith’s masterwork, The Wealth of Nations, provides the basis for these beliefs: “the natural effort of every individual to better his conditions…is so powerful a principle, that it alone…is only capable of carrying on the society to wealth and prosperity.”

What Smith’s economic ideology does not include, as indeed no ideology includes, is the human variable, or the means of making the ideology, as Peel fought for, “applicable to the real world.” Even the “natural effort of every individual” will not prove enough when he is harried by foreign despots, a lack of resources and education, and poor mental health. Unfortunately for the prime minster, his cries fell on deaf ears. The policymakers held staunchly to Smith’s ideology and believed erringly that a nation which could launch a rebellion could use those same energies to launch itself out of turmoil. The fact that the policymakers were also from Peel’s rival Whig party probably didn’t help much either.

These factors, coupled with his failing health, the burden of the Famine tragedy, and also the hatred he bore from his own Tory party, caused Peel to resign his post in 1846. Coogan chronicles the prime minister’s final broken years and his minor heroism pointedly.

With Peel’s resignation there was nothing to stop the implementation of Trevelyan’s economic policies, which combined both the misguided interpretations of Adam’s Laissez-faire with a blunt jingoism. Before the policies take root, Coogan presents Trevelyan in a few choice details, quoting Yeats in describing him as “a soul incapable of remorse or rest” and citing details found at the Trevelyan estate, where the civil servant kept a stained-glass window of himself depicted as “St. Michael the Archangel in golden armor” under the inscription by St. Paul: “I have fought the good fight, I have finished my course.”

For Coogan, Trevelyan embodies the extremes of Irish racism and misguided belief, second, only to the idea of Laissez-faire, of which was that “poverty was the fault of the individual.” Yet Trevelyan serves also to embody Coogan’s more extreme dual thesis that “God sent the blight, but the English made the Famine,” and that the English executives used the Famine to propel a Hibernian genocide.

Tim Pat Coogan

■

As to the latter, much of Trevelyan’s records substantiate that possibility. His feelings towards an Irish free state were certainly indignant, as is expressed in one of his correspondences: “one of the greatest of the delusions which have been put into the heads of the peasantry is that they are a nation.” While this was technically true (Ireland would remain apart of the Union until 1922), his attendant letter, contained in the book’s excellent, though short, appendices, exemplifies not a small amount of British imperialistic ideologies as well as bigotry directed towards the peasantry and the Catholic clergy. One need see only the disturbing, anthropoid depictions of the Irishman in the early cartoons of Punch magazine to get a sense of this anti-Irish zeitgeist.

His policies for the distribution, or non-distribution, of relief rations, and for the exportation of good crop in Ireland despite the starving masses of over 3 million (it is important to note too that Ireland’s population in the mid 19th century was just over 8 million), also qualify a degree of sadism.

Coogan cites several stories of horror and misery to back this point up. Following through with his mission to render the history as true and objective as possible, he unflinchingly delivers pages of starving children, noisome workhouses, putrid disease, and obtuse government. One story, referenced in his Introduction, gives the account of Nora Connelly: a poor peasant woman who walked miles on foot to a food distributor so that she could feed her dying children. Turned away because her name was not on the list of those to be fed, she walked back to her home where she discovered that four of her children had starved to death. Only later was it realized that she should have been on the list but that a careless official had entered her name incorrectly.

While stories such as these are meant to signify governmental obliviousness and a lack of general human kindness, they do not prevent Coogan from implying that the blame should be placed directly upon Trevelyan. Such a maneuver is repeated in the later chapters on peasant evictions, workhouse conditions, and immigration.

Trevelyan certainly worsened the conditions of the Famine, yet much of this can be chalked up to basic incompetence, which Coogan himself acknowledges when he details the ineffectual Corn Laws, (laws that governed the importation of Indian maize) and posits that the British “literally did not know a great deal about corn,” or rather, enough about the corn to instruct the Irish on how it should be ground and digested, which was done in a series of lengthy and inaccurate articles that resulted in widespread deaths caused by dysentery and scurvy.

Coupled with this were other negligible reports that, flagrantly misleading, would be laughable if their results weren’t so tragic. At the height of the first year of the Famine and during the outbreak of corn-related diseases, Trevelyan was fed information stating that there were “ ‘scarcely any’ gastric complaints” and that “ ‘the general health of the people has wonderfully improved.’ ” How he managed this information with the thousands of gastric disease-related deaths can only be left up to conjecture.

Whether Trevelyan chose to believe any of what he was told doesn’t seem to matter to the author, who focuses more or less only on how the man reacted. And yet it doesn’t appear to be too far a stretch to assert that Trevelyan, already proving himself highly delusional in his self-depiction as archangel Michael, caved again to willful delusion and chose his policies not as a means of genocide but in the interests of self-preservation.

Although this theory might not hold during Trevelyan’s later moments, such as when he learned of the massive farmer deportation: “I am not at all appalled…that seems to me to be a necessary part of the process,” or when he presided over the relief efforts during the Famine’s worst year (“Black ‘47”): “with the smallest amount of abuse [we will] encourage such principles of feeding and action…to improvement of the social system,” it is still a possible avenue the reader wishes the author didn’t leave unexplored.

Though a study of anti-Irish psychology could very well encompass its own book, room could have been made had the author chosen to cut his chapter on immigration, which is a brilliantly treated topic in Wherever Green is Worn but which meanders here.

Even so, the unsparing depiction combined with his laboriously conducted research mark The Famine Plot as fine a work as any in the chronicles of Famine books. Should the reader choose to disagree with the contention that England’s role was one of extermination, he will nevertheless yield to Coogan’s evidence that historians have long undermined the tragedy’s shocking reality. What’s most important is not that we place the blame on all those responsible, but that we honor and remember all those who suffered.

▲