▼

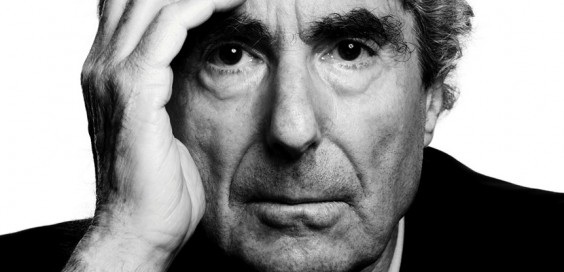

Notes on the Occasion of Philip Roth’s Retirement ◆ by Kevin Howley

Last October, a few months shy of his 80th birthday, Philip Roth, America’s most celebrated living novelist, quietly announced his retirement. Roth made the disclosure in an interview with Les Inrockuptibles, a French cultural magazine. Weeks later, Salon confirmed Roth’s retirement with his publicist at Houghton Mifflin and the Paris Review translated Nelly Kaprielian’s complete interview with Roth. Assessing his handiwork – some thirty books over the course of more than half a century – Roth invoked not a man of letters, but a sports legend from his youth: “At the end of his life,” Roth recalled, “the boxer Joe Louis said: ‘I did the best I could with what I had.’ This is exactly what I would say of my work: I did the best I could with what I had.” Roth’s “best” is a poignant, incisive, inventive, raucously humorous, sometimes controversial body of work. Any appreciation of Roth’s legacy, however modest, would do well to take Roth’s own assessment as a starting point. What was it, then, that Roth had to work with?

Born in Newark, New Jersey in 1933, Philip Roth was raised in a working class, secular Jewish household: a milieu Roth plumbed for his antic comedy, most notoriously, Portnoy’s Complaint, as well as his darkest imaginings, The Plot Against America. The Newark of Roth’s youth – a vibrant urban space with decent schools, ethnic neighborhoods, and a bustling downtown figures prominently his work. As does Newark after de-industrialization, white flight, and the racial tensions of the 1960s that decimated a quintessentially American city. Roth’s evocations of Newark are rarely romanticized; instead, Newark serves to ground his characters, and their stories, in a discrete and discernible time and place.

■

Of his forsaken city, Roth writes in the Pulitzer Prize-winning American Pastoral, “It was Newark that was entombed there, a city that was not going to stir again. The pyramids of Newark: as huge and dark and hideously impermeable as a great dynasty’s burial edifice has every historical right to be.” The calamity that befalls Newark provides the backdrop to the familiar catastrophe that wrenches the novel’s protagonist, Seymour “Swede” Levov, from his “longed for American pastoral … into the indigenous American berserk.” Levov’s harrowing tale, as recounted by Roth’s most enduring character, the writer Nathan Zuckerman, is part of a trilogy that includes I Married a Communist – a period piece set in the McCarthy era – and The Human Stain. Arguably one of Roth’s most vivid, sympathetic, and penetrating portraits, The Human Stain tells the story of Coleman Silk, a respected professor of classics at a small liberal arts college in Western Massachusetts, and his great undoing on the alter of political correctness at the height of the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal.

The gravity of Roth’s work finds its antithesis in the comic absurdity of some of his most memorable and imaginative fiction: The Breast, wherein the protagonist, Professor David Kepesh, another of Roth’s recurring characters, undergoes a Kafkaesque metamorphosis into an enormous mammary gland; Our Gang, an uproariously indignant response to the excesses of the Nixon White House; and, most famously, the aforementioned Portnoy’s Complaint – the book that made Roth rich and reviled. At once a product and send-up of the sexual revolution of the 1960s, Portnoy’s Complaint signaled Roth’s arrival as one of America’s preeminent satirists.

Alexander Portnoy’s psychoanalytic confession of sexual defilement and insatiable appetite to the silent therapist, Dr. Spielvogel, is an extended Jewish joke. Of course, not everyone got the joke. Despite its rebellious, ribald, and unprecedented assault on sexual taboos, feminists decried Portnoy’s Complaint, chiefly, but not exclusively, for its caricature of Mary Jane Reed (aka The Monkey). Others lambasted Roth for exploiting, reinforcing, and legitimating stereotypes of Jews and Jewish life. This was not the first, nor would it be the last time, Roth provoked the ire of Jewish readers. His first published short story, “Defender of the Faith,” created an uproar among those who took the tale to be the work of a “self-hating Jew” whose comedy did nothing to dissuade the goyim from their distaste and distrust of the chosen people.

Roth’s work provokes and explores a central question: What does it mean to be a Jew living in postwar America? This thematic concern – some, including Roth in the guise of any number of his protagonists, might call it an obsession – is a particularly rich vein for his fiction. Indeed, Roth’s autobiographical dexterity – as much a reaction to his perceived self-hatred as it is a declaration of his Jewishness – proved an excellent vehicle to interrogate the relationship between fact and fiction, lived experience and imagination, authors and their creations. Most evident in the Zuckerman trilogy – The Ghost Writer, Zuckerman Unbound, The Anatomy Lesson – this theme permeates other work as well. Consider, for example, Operation Shylock, wherein the writer Philip Roth confronts his double, or Roth’s nonfiction, including the deeply moving account of his father’s prolonged illness, Patrimony, and The Facts, Roth’s autobiography, in which Nathan Zuckerman writes an afterword that puts the book’s veracity into question.

And yet to define Roth exclusively or even primarily as a Jewish writer limits our understanding, and appreciation, for his art and craft. One needn’t have grown up a Jew to know the shame and guilt that adolescent boys, fond of whacking off, know all too well. One only needs a prick to register a familiar laugh, as when Alex Portnoy, fearing the worst – that his self-abuse has given him cancer – just can’t leave it alone. Inevitably, inextricably, Portnoy’s paranoia yields to his desire: “If only I could cut down to one hand-job a day, or hold the line at two, or even three! But with the prospect of oblivion before me, I actually began to set new records for myself. Before meals. After meals. During meals.”

Then there is Roth’s love for that other national pastime: baseball. Consider the audaciously titled The Great American Novel, which tells the story of the ill-fated Port Ruppert Mundys: a team so bad it has no home field. A team so inept that the franchise has been stricken from all of baseball’s recorded history. When the Mundys actually win a game – albeit an exhibition game against the inmates of a local insane asylum – the players recount their exploits with the same gusto and gravitas you are likely to hear when Bloomington’s boys of summer enjoy a bit of tailgating down at Twin Lakes softball field. “‘Yep,’ said Kid Heket, who was still turning the events of the morning over in his head, ‘no doubt about it, them fellers just was not usin’ their heads.’”

Roth’s gift for farce is matched by his single-minded devotion to the novel. From the writerly introspection of his most radical work of fiction, The Counterlife, and his editorial stewardship of the Penguin series, Writers From the Other Europe, to his collection of literary interviews and criticism, Shop Talk, this much is clear: Roth is a writer’s writer. In his exit interview, Roth said, “I’ve given my life to the novel. I’ve studied it, I’ve taught it, I’ve written it, and I’ve read it. To the exclusion of practically everything else. It’s enough! I don’t feel that fanaticism about writing that I felt all my life. The idea of trying to write one more time is impossible to me!”

If Roth, trickster that he is, is to be believed and he really is retired, his final series of short novels, culminating with Nemesis, a study in “the tyranny of contingency,” caps a luminous and prolific literary career.

[Kevin Howley is professor of media studies at DePauw University. He is indebted to Professor Parke Burgess, his undergraduate advisor in the Department of Communication Arts & Sciences at Queens College, for introducing him to the work of Philip Roth.]

▲