▼

“…but one mustn’t grumble too much” – Nuclear apocalypse in Richard Lester’s film, The Bed-Sitting Room ◆ by Tom Prasch

Some readers may find this hard to believe but many years ago, before the zombie apocalypse was all the rage, nuclear apocalypse was quite fashionable. The nuclear nightmare may have been somewhat less alarming than a world consumed by zombies but nevertheless, at the time, it seemed equally plausible. Frightening books were published, grim PBS documentaries aired, and of course there were movies, most somber but a few satiric. One of the best of these was Richard Lester’s The Bed-Sitting Room.

A man in tattered formal wear—it only looks proper from the chest up—knocks on a door that no longer leads to any house. He announces “I am the BBC,” and he sticks his head behind an empty television box to read “the last news.” The Central Line tube still works, thanks to a lone man on a bicycle, England’s sole source of power, but when a family that has been riding the circuit for years decides to leave (because the vending machines in the underground have run out of chocolate bars), the still-functioning escalator drops them into piles of ash. A policeman roams the ruined landscape in a Volkswagen beetle dangling from a hot-air balloon, shouting warnings to the meandering nomads below to “keep moving.” A postman carries a cream pie across the blasted landscape, through ponds of muck, across mountains of ruin; you probably know what will happen when it reaches its destination. Such are the conditions for what’s left of London and Londoners (all twenty of them) in the wake of nuclear apocalypse in Richard Lester’s dark farce.

Bizarre nuclear mutations beset the population: Lord Fortnum fears (quite rightly, it turns out) that he is turning into a bed-sitting room; mother transforms into a chest of drawers (we get a hint of the direction of her change when she can no longer move and, weeping, opens a drawer in her chest to fetch a handkerchief) and father turns into a pigeon (who then commits suicide, providing a dark last meal for the family). Penelope, meanwhile, the daughter of the roving family, is 17 months pregnant and worries about the “monster” in her womb (when she tells her boyfriend, Alan, “I can’t bear to go through with it … having this monster,” he reassures her, sort of: “Well, no one else can have it, can they?”). Meanwhile, raucous instrumental music-hall tunes play constantly in the background, suggesting a sort of deranged Kurt Weill, save when they are replaced now and again by strains of “God save Mrs. Ethel Shroake, of 393A High Street, Leytonstone” (the awkward refiddling of the traditional tune to accommodate the nearest surviving relation to the preapocalyptic queen).

Lester assembled a remarkable cast of comic actors, many with rich experience in theater, music hall, and television comedy (Dudley Moore, Rita Tushingham, Spike Milligan, Peter Cook, Marty Feldman, Mona Washbourne, and Ralph Richardson, among others). He adapted Milligan’s stage play to the visual conventions of cinema, filming in a range of devastated rubbish-heaped locations. He mixed pun-heavy pratfalling music-hall comedy with the bleakness of Samuel Beckett (or perhaps just amplifying the vaudeville side of Beckett’s Godot). The result is a stark dark farcical vision of post-nuclear apocalyptic Britain. Comic and depressing in equal measure, the film offers a rich opportunity to examine the limits of genre in treatments of the apocalypse. Can sketch comedy make nuclear apocalypse its territory for the length of a feature film? Does the end of civilization as we know it work well as farce?

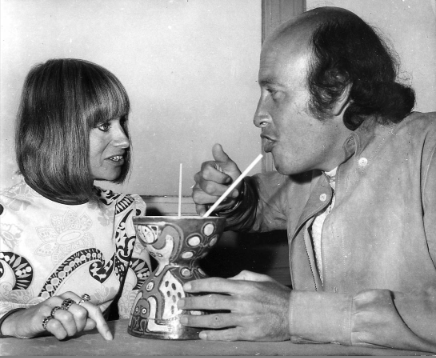

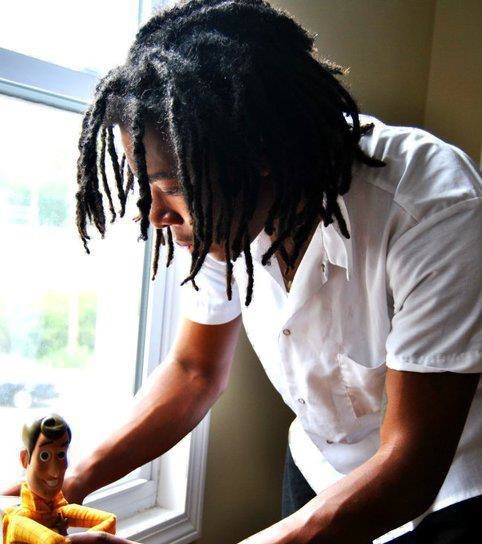

Rita Tushingham & Richard Lester

■

The short answer to the question, at the time of the film’s release, was: no. Lester had, in the mid-1960s, established a name for himself with a series of highly popular, inventive film comedies—the two Beatles films, Hard Days Night (1964) and Help! (1965), mod-London-set The Knack (1965), and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966), all of which seemed to catch something of the mood of the rapidly changing decade. But, later in the 1960s, the hit machine faltered; the two films that immediately preceded Bed Sitting Room, the antiwar comedy How I Won the War (1967) and a swinging-San Francisco-set romantic drama, Petulia (1968), failed to spark at the box office, and The Bed Sitting Room truly bombed.

Typical of the film’s reviews was the thrashing Vincent Canby gave it in the New York Times: “The movies of Richard Lester … seem to get worse in direct relation to the seriousness of their intentions. The Bed Sitting Room is Lester’s most seriously intended film to date…. Apocalyptic or prophetic cinema, whether it is in the form of science fiction or farce, demands more than picturesque sets and costumes and a decent, concerned sensibility.” Other reviewers were similarly unenthused. While making the film, Lester noted for the New York Times: “The fact that they don’t know what a bed-sitting room is in America poses a problem, of course,” but he seemed relatively unconcerned about the point. Perhaps he should have worried more, but the obscure title likely had less to do with the film’s utter failure than the inability of audiences to appreciate Lester’s tone and style. They stayed away in droves. As Roger Ebert noted in 1976: “It was … a total disaster at the box office. So great was its failure, indeed, that Lester didn’t get another directing assignment until 1974 and The Three Musketeers.” The time was not ripe for apocalyptic farce.

Lester himself seemed to have second thoughts about the work, indeed, even as he filmed it. He explained to Mark Shivas of the New York Times, in an article tellingly titled “Well, the Bomb Is Always Good for a Laugh”: “The film will be much more barren than the play, much sadder and less frenzied. There are moments of people sitting alone in an empty field, hungry and trying to eat grass. It’s sad, and I didn’t feel sad at the play. I hope, though, that it’ll be as funny as the original as well. …I’m not able to tell whether it’s funny, because I feel terribly sorry for these people, cartoons though they may be. They’re cut-outs moving through abstract landscapes.”

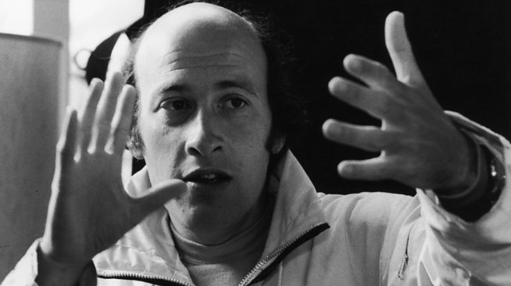

Lester

■

This hardly sounds like advance publicity that will bring audiences into theaters. Lester even shared some concerns about potential box office during filming: “farce seems to me one of the best ways to do this, partly because more people are inclined to see a farce and partly because the result of the bomb can perhaps be more easily suggested by giving surrealist parallels than by showing actual realistic desolation…. Actually, I’d have felt much more confident about this had How I Won the War been seen by a larger number of people.”

Decades later, talking to Steven Soderbergh, comparing his film to Milligan’s source play, Lester noted that the play was “funnier.” Soderbergh asked: “Do you think literalizing stuff hurt it?”, and Lester responded: “The only way we could try to literalize it was to produce excesses like a huge pile of boots and teeth and things like that…. Spike didn’t like the film particularly. He felt it was bleak and that worried him.…. It was a depressing film to work on. It was painful. And that came over.”

The Bed Sitting Room may have simultaneously anachronistic and ahead of its time. For Lester, anachronism reflected a deliberate choice, as he explained at the time: “I was interested in how the Bomb has become a sort of period piece, how it’s almost ‘that old thing’ we mention rather apologetically after we’ve discussed violence, civil rights and Vietnam…. I thought it would be nice to remind the audience that the B-52s go on flying, and farce seems to me one of the best ways to do this.” Roger Ebert, writing in 1976, argued that the film was released before its time: “If Monty Python’s Flying Circus had never existed, Richard Lester would still have invented it. In 1970 [sic] he directed The Bed Sitting Room, a film which so uncannily predicts the style and manner of Python that we think for a moment we’re watching television. The movie’s dotty and savage; acerbic and slapstick and quintessentially British.” It is not clear, however, if this constitutes an endorsement by Ebert.

So what, finally, is this film about? Usually, the answer to such a question could begin with a quick outline of the plot for those who have not seen it or have seen it too long ago. But here, there is no plot to speak of. For the most part, there are disconnected characters or small groups whose courses intersect in arbitrary ways as they meander across the devastated postwar landscape.

We can notice some minor character arcs, perhaps most notably the romance plot between Penelope and Alan, although that is complicated by the fact that she is already pregnant and by her father’s decision to marry her off to Bules Martin for political reason (the father having just been selected to be the new prime minister, on the basis of the length of his inseam). Still, the longest monologue in the film connects to the romance plot, when Penelope talks about the boy then asleep in her lap, although as declaration of love her speech is rather odd: “I will say this for him, I can’t really say anything for him, except he’s like a sheet of white paper. I haven’t seen a sheet of white paper for years I could draw a face on.” And there’s another developing romance as well, between the bed-sitting room and the cabinet of drawers.

Beyond such stray bits, however, the only arc is downward. Through the course of the film, conditions worsen, and near its close, as a radiated fog arrives (made only slightly amusing by gasmasks with funny animal faces on them), as Penelope’s finally-born baby dies, as starvation looms, things look very bleak indeed until the police inspector arrives, dangling on a ladder from his balloon and announces: “I’ve just come from an audience with Mrs. Ethyl Shroake and I’m empowered by her to tell you, that in the future clouds of poisonous nuclear fog will no longer be necessary, mutations will cease any day…. All in all, I think we’re in for a time of peace, prosperity, and stability. The earth will burgeon anew, the lion will lie down with the lamb, and the goat give suck to the tiny bee. At times of great national emergency, we often find that a new leader tends to emerge. Here I am, so watch it!” Even the rosy ending is undercut, however, by a final BBC news flash: “I have great news for the country. Britain is a first-class nuclear power once again.” (Never mind that the new status is only earned because one undelivered bomb has been returned to sender by the postman, with fees due; it still suggests something about lessons not learned.)

Over the course of this unstory, three broad targets for Lester’s satire emerge. The first and most obvious though in some ways least important, is the war itself, and specifically the dynamics of a possible nuclear war. The BBC man’s “final news” near the outset makes this clear, as he reports the Prime Minister’s speech: “On this, the third, or is it fourth, anniversary of the nuclear misunderstanding that led to the third world war, here is the last recorded statement of the Prime Minister, as he then was… ‘I feel I am not boastful when I remind you that this war was the very shortest war in living memory: 2 minutes and 28 seconds up to and including the grave process of signing the peace treaty. The great task of burying our forty million dead was also carried out with great expediency and good will.” The nature of this new war is such that no one served, or is sure what happened; as Bules Martin says, when Lord Fortnum tells him he slept through the war and never got to serve: “Neither did I. Mind you, I was standing by, ready to face the enemy, whoever they might be, but I couldn’t find them. Tell me, do you know, who was the enemy?”

But nuclear-war gags can only go so far, and indeed the broader focus of Bed-Sitting Room’s comedy is about two aspects of British society thrown into comic relief by the new conditions of the postapocalypse: deeply rooted institutions, and even more deeply rooted traits of character. Institutions held up for abuse range from formal political ones like the National Health Service to more socially constructed institutions like the class system. That political institutions have now tended to be reduced to a single person—a one-person military that carries out both sides of a conversation just to make up for the fact that there is no one to follow his orders; a single nurse comprising the National Health Service, and one played alarmingly by Marty Feldman; that man on the bike who is the Electrical Board, and who has to keep peddling to keep the juice flowing—makes the institutional comedy a bit easier. That they are still filling out forms (even for a custard pie’s delivery), or that, when only twenty people are alive in Britain, it would be anyone’s concern who among them was closest in line to the throne, seem absurd, but it is the sort of absurdity that makes us question those conventions in our own time as well. Social conventions, most notably the class system, work in a similar way. When everyone is ragged and starving, the logic of titles and privilege seems especially unclear (particularly when how those titles were determined is also fuzzy; Lord Fortnum notes that he “acquired the title from a social person who had fallen on hard times”). But that these aristocrats would seek to maintain their class views and prejudices under the changed circumstances seems more absurd still. Thus, when Lord Fortnum learns in what neighborhood he has made his final transformation he pleads with Bules Martin: “Put a sign in the window. No coloured. No children. And definitely no coloured children.” That such views are still appropriate for someone who is now a bed-sitting room—and, frankly, a rather shabby one at that, much improved when the chest of drawers joins him—makes such views seem more absurd, but again in a way that opens them to question outside the limited realm of the film’s postapocalyptic timeframe.

Beneath these satiric targets, and informing the structure of them, is the film’s most central target and interest: that stiff-upper-lipped British character. Bules Martin, holding a bottle of milk up to the light and looking somewhat dubiously at the odd color of the stuff, comments to himself: “Radiation’s rising. Still, mustn’t grumble too much.” The theme is picked up by Alan later in the movie, when he tells Penelope, “We’ll just have to keep going.” “What for?,” she wants to know; “Because we’re British,” he tells her. Penelope, in fact, is having none of it: “British, what a lot of use that is. We don’t even know who’s won the war. Run out of food, no medicine, we’re eating our parents. British!” But even her protests serve to accentuate the theme: that it is the peculiar character of the British to soldier through whatever the circumstances, and to pretend as much as possible that there just is nothing wrong.

That Britishness makes these characters endearing, connects us to them in ways that their roles do not quite justify. That Britishness makes this story more tragic, since after all no one is ever convinced by deus ex machina as a way out of hopeless situations (it’s why Aristotle panned Euripides, after all). But that Britishness also makes the film more insular, since audiences outside Britain not only are unlikely to know what a bed-sitting room is but will have dim if any connections to the institutions the film mocks, the comic stylings it borrows from music-hall conventions and Goon Show bits, or the locations it ravages. That Britishness is thus the film’s great virtue and the source of its box-office doom.

Photo caption

Rita Tushingham and director Richard Lester.

P

Photo caption #2

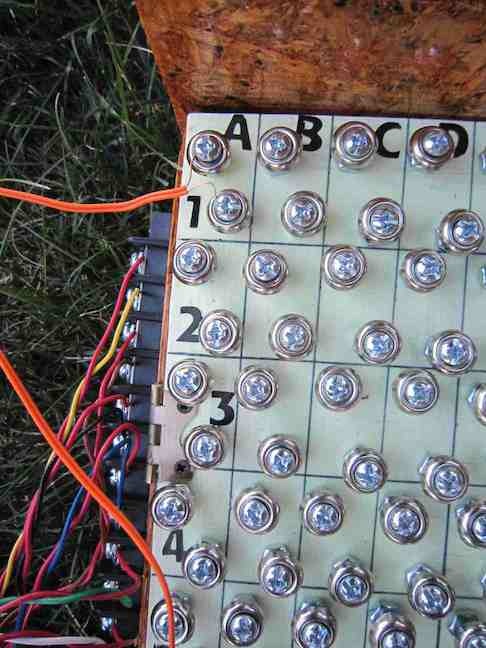

A policeman roams the ruined landscape in a Volkswagen beetle dangling from a hot-air balloon in The Bed Sitting Room.

The Ryder ◆ August 2013