Charlie Hebdo: Choosing Sides

● by Ethan Sandweiss

On January 7th at 11:30, I was finishing my language class at Lyon’s Alliance Francaise. Less than three hundred miles away, the employees of one of France’s premier satirical magazines were being slaughtered.

Despite the rise of terrorism all over the world, France has, up until the attack on the Charlie Hebdo office, remained remarkably untouched. I’m working in Lyon as an au pair, but when I first heard about the attack (through my American family), it seemed far off and small, as if in another country. Being a foreigner here, it’s sometimes hard for me to gauge public sentiments in France, but the reaction to the Charlie Hebdo attack was nearly tangible. Religious and cultural tensions in France have been on the rise for years, but the attack became an affirmation of national fears; domestic terrorism had come to France. And the perpetrators were, by nationality, French.

On Sunday, I joined a rally of 250,000 demonstrators at Mon Plaisir: the historic sight of the world’s first film. The rally was really incredible, like nothing I’d ever seen. An endless stream of demonstrators, with pencils, signs, yarmulkes, cameras, children, and hand-rolled cigarettes stretched from the square at Mon Plaisir to the city’s center Bellecour and beyond. The demonstration sent a clear message that, Jewish, Christian, or Muslim, we are the people of France, and we are free. Still I can’t help but think back the the past several American massacres: the Boston Bombing, Sandy Hook, the Aurora Theater, and even a decade earlier to 9/11. Following the attacks, there was always a sense of unity and a shared desire by all to uphold the values of peace and freedom. Over time, however, the same catastrophes that unified us began to divide us as we debated how to interpret these events and how to respond. Is this sense of national unity in France going to last?

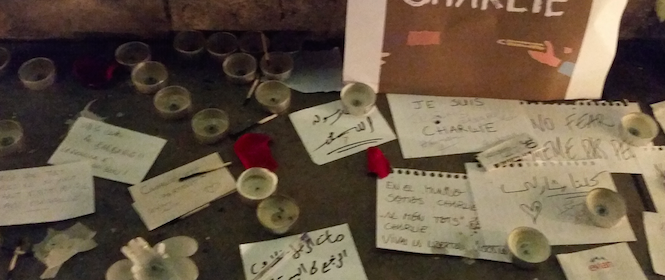

Demonstrators At Lyon’s Charlie Hebdo Rally

[Photos by Ethan Sandweiss]

●

The government of France doesn’t seem to think so. On the Monday following the attack, 10,000 troops were dispatched across the nation to guard certain vulnerable sites: Jewish Schools, Synagogues, and Mosques, in particular. Both Jews and Muslims have faced increasing difficulties in France as of late. For Muslims, it’s often a legal battle, following controversial bans against the wearing of burkas and the construction of minarets on Mosques. For Jews, it’s a problem of violence. Vandalism and anti Semitic attacks have grown increasingly numerous, and twice the number of Jews emigrated from France to Israel in 2014 than in the year prior.

The Saturday after the Charlie Hebdo attack, I returned to my favorite Algerian cafe to write a letter to my family back home in America. I heard “kill the Jews” for the second time there, this time coming from the bartender with the white beard. He’s the same man who always greets me with a smile and knows that I don’t take sugar with my coffee. Here in France I’m a bit of an invisible Jew; I don’t wear a yarmulke or tzitzit, I don’t go to synagogue, and I don’t keep kosher. I see anti Semitic graffiti on the streets and I hear unkind words in cafes, but I feel a little like a ghost, invisible and watching.

I don’t think that Islam is inherently anti Semitic more than any other religion. The frustration of some of Europe’s Muslims at their alienation manifests as anti Semitism, in the same way that people in times of societal and economic crisis have often found a scapegoat group to blame. At the root of the issue is the conflict of acceptance and alienation, tradition and assimilation. In France, where so much importance is placed on assimilation and homogeneity, it can feel impossible for Muslims to balance religious and national identities.

Picking the kids up from their Algerian nanny, I began a conversation with her daughter: a university student here in Lyon. Like many of France’s Muslims she finds herself both critical of the killers and of the magazine Charlie Hebdo itself. “I am not Charlie,” she said, referring to the Charlie Hebdo movement’s famous slogan. “I am French and I am Muslim, but here they don’t let you be both. You have to choose.” For Muslims who feel that they can neither support offensive caricatures of their religion nor tolerate religious extremism, it’s difficult to find a place to fit into French society. The slogan that began appearing on walls and billboards the day after the attack, “Je Suis Charlie,” is well intentioned, but implies that the magazine’s mockery of Islam is, in a way, honorable.

Finding the balance between preserving freedom of expression but preventing hate speech has been the central conflict in response to the attack. Of course, a satirical magazine has the right to publish what it will, but does that mean it should? Even before the attack, Charlie Hebdo had no shortage of enemies; the magazine mocked Judaism and Christianity, the political right, pretty much anything that it could. Before January 7th, the magazine, though notorious, had a circulation of only about 10,000 issues per week. Now, it’s hard to buy an issue quickly enough. Three million copies were printed the week after the massacre, but by the time I reached the Tabac at ten, none remained. Charlie went from being a despised fringe publication to being an international symbol of free expression in just one day.

The support here in France for the magazine seems almost universal. You can find Charlie posters at bus stops, schools, and pretty much every restaurant. The horrible tragedy and the threat to free expression have rightfully received the attention they deserved. But another voice is so quiet that it almost can’t be heard: a voice that asks if, despite the tragedy, Charlie Hebdo was doing the right thing. For now, the people of France are unified. But this is a complicated peace: one that isn’t as black and white as the posters hung all over the city.