An Attempt At Processing The Death — And Life — Of Robin Williams

● by Will Healey

I had just walked off the field after a pick-up Frisbee game and, seated in my car, checked my phone for any messages. There was a missed call and a voicemail from a friend I’d been playing phone-tag with for several days; there was a text, too, from that same friend, saying “Robin Williams died, supposedly a suicide…”

I remained in my car, in the parking lot of the elementary school where we’d played, for what must have been twenty minutes. At first I was stunned by the sudden news that he was dead; but my shock soon turned to disbelief, and I switched to journalist mode, using the Internet on my phone to confirm that it was true. Once corroborated by a glance at a credible news outlet, I was hit by a flood of images of many of his performances enmeshed with who I was, where I was, and who I was with when I watched them. It was like my life, and his life as a performer, flashed before me. Mork & Mindy, Hook, Aladdin, Mrs. Doubtfire, The Birdcage, Good Will Hunting; my family, my friends, growing up.

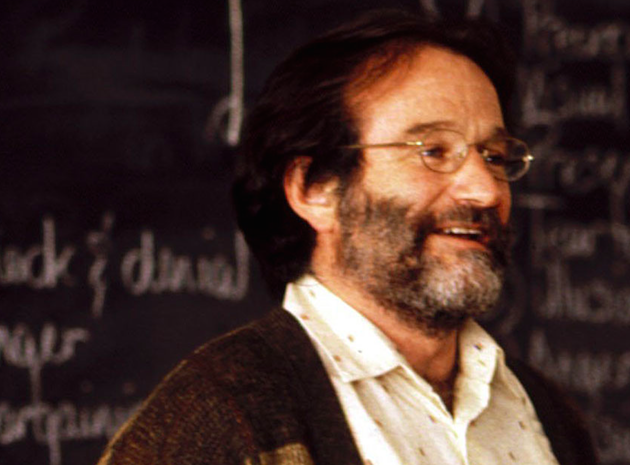

Good Will Hunting

●

I’d always appreciated Robin Williams as an entertainer, though in recent years I truthfully found him more exhausting than anything else, mostly because the only times I saw him were in shtick-y interviews where I’d find myself pleading with the TV for him to relax, shut his brain off for a second, to stop being the entertainer…but he couldn’t. He seemed so manic; I often wondered how he could live with his mind going a million miles a minute. I no longer went to see his films. The Night at the Museum franchise, Happy Feet, those vehicles didn’t hold the same magic for me, an adult, as they probably do for kids today. I’d long since left Neverland. Robin Williams had served his purpose for me, and I no longer needed him. But when I heard that he was dead, I realized just how big a part of my life he’d been. In an admittedly parasocial sense, I grew up with this guy. From my car in the parking lot, I sent a group text to my family, a rare act usually reserved for sharing big things like the Red Sox winning the World Series, or videos of my little niece doing something adorable. This felt appropriate, somehow. We’d lost someone who gave our family much entertainment and great joy. We’d lost one of our own.

And then my mind shifted to the manner of his death. Suicide? I’m not saying that suicide is a fitting end for any person, but it felt especially inappropriate for him. I had heard of Williams’ wild days with drugs and alcohol in the late 70’s and early 80’s. I knew the story about how he was one of the last people partying with John Belushi before he died, and I’d heard his bits about cocaine. I also knew that he cut all that stuff out when his first child was born in 1983. Williams relapsed into alcohol in 2003, and struggled with it for years before checking into rehab in 2006. I remember hearing that he had checked into an alcohol treatment center earlier this year, but I didn’t think much of it. I did not see this coming. I wonder if anyone did.

Shortly after his death, Williams’ publicist stated that he had been struggling with severe depression prior to his death. Shortly after that, Williams’ wife stated that he had been sober before his death, but revealed that he had been diagnosed with the early stages of Parkinson’s disease.

After Williams’ death, the outpouring of grief and tributes throughout social media made it clear that the loss was felt by many. I saw post after post of people’s favorite quotes, pictures, and clips. I thought about my favorite Williams moments, and ironically, they weren’t any of the bombastic live wire comedic performances. They were the nuanced, dramatic moments where he laid himself bare. His impassioned performance in Dead Poets Society. His Academy Award-winning performance in Good Will Hunting- particularly two moments- the warm glint in his eye when his character, Sean, shares with Will the information that his wife used to fart in her sleep, saying “that’s the good stuff;” and the shift in his voice in the classic park scene when he says to Will, “If I asked you about love, you’d probably quote me a sonnet, but you’ve never looked at a woman and been totally vulnerable.” That one scene might have single-handedly won him the Oscar.

In the days following his death, many previously unheard stories came out about his generosity, the quiet acts of kindness that he didn’t intend for anyone to ever know about that showed the true measure of the man. The bucket list video he sent a New Zealand woman dying of cancer shortly before his death. The time he chartered a jet to North Carolina to spend the day with a young girl who would die two weeks later from brain cancer. Or the video of the time he had a tickle fight with Koko the Gorilla. Some things were higher profile, too- the many trips to Iraq and Afghanistan to entertain the troops. Helping Comic Relief raise more than 50 million dollars during its twelve-year run to fight homelessness in America. Granting countless wishes to kids with terminal illnesses through the Make-A-Wish Foundation. Supporting the St. Jude Children’s Hospital for several years.

When his close friend Christopher Reeve was convalescing after the riding accident that left him a quadriplegic, Williams snuck into the hospital dressed as a doctor to cheer him up. According to Reeve, it was the first time he’d laughed since his accident. Williams continued to be close with Reeve over the next several years, and even helped him pay his medical bills. After Reeve and subsequently his wife, Dana, died, Williams helped provide support for the Reeve’s son, who was fourteen at the time.

Robin Williams almost came to the Comedy Attic try out some new material in 2010. Jared Thompson, owner of the Comedy Attic to “Unfortunately, it never happened, I don’t know exactly what he ended up doing instead, but the fact that we were even involved in a conversation about it was just fantastic,” Thompson said.

Williams did perform at the IU Auditorium in 2009. In an email exchange, IU Auditorium Director Doug Booher reminisced about meeting Williams, and shared this story about the night of his performance:

“There was one particular guest that night who he (Williams) was most interested in meeting. We had learned that a young teenage boy, who was being treated for a significant medical condition at IU’s MPRI, was one of Mr. Williams’ biggest fans. His parents wanted to surprise him with a trip to the show, but because of the costs of his ongoing treatment were only able to pay for a balcony ticket for their son, and one parent to accompany him. When Mr. Williams learned about this, he asked that the young man and both of his parents be invited to be his guest, sit in the front row, and attend a private backstage meet and greet. After the show, when we escorted the boy back to meet Mr. Williams, I am not sure which of them was more excited. Mr. Williams and the young man shared stories of their lives, recounted favorite movie lines and roles, and even took turns impersonating Mr. Williams’ various performances. Toward the end of their visit, Mr. Williams shared some very personal insight with the boy about perseverance and his optimism for the boy’s recovery. With tears near the surface for everyone in the room, they exchanged contact information and hugs. It was truly a genuine moment that defied all of the common beliefs about celebrities, and reinforced the incredible power of laughter and love.”

●

I read somewhere that Williams viewed performing as a means to let him get to his true passion in life- making people feel good. It saddens me to think that someone who gave so much happiness to so many in the end had none left for himself. Perhaps the best way to honor Robin Williams would be to remember him less for the circumstances of his death and more for the joy he brought in life.

The Ryder ● October 2014