Fiction: Animals Begin On The Porch In Days And Nights Of Dark War

by Willis Barnstone

For Bruno Shulz (1892-1942)

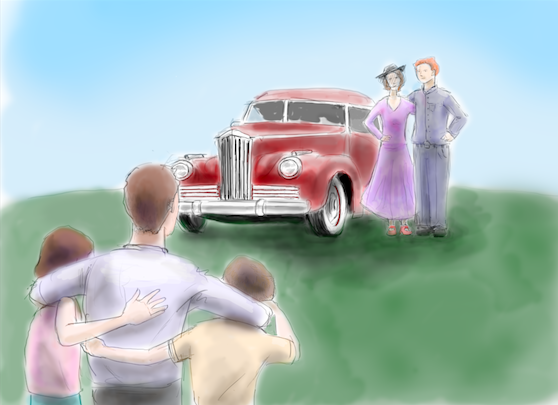

Animals begin on the porch. My daughter sees them first and she says they come in all sizes and they are goats, but my son says no they are deer, perfectly-formed deer who have come in from the forests and their coats are immaculately clean pelts of Irish setters but they are certainly not dogs, and I wonder what is happening to my son’s and daughter’s eyes, because I can see they are horses, and possibly Egyptian animal deities of revenge and resurrection, and I wonder why these live statues have settled here on our porch in days and nights of dark war in far continents, live gods in our house in 1942 when our people are also contending; and while we are descending the porch the animals we’ve just spotted vanish yet we are all now in the sloping fields, family and many more animals or maybe deities, and we are walking slowly up these meadows of grass and wildflowers, and I am frightened, not of the still horses who are certainly figures of grace but of my own body, because suddenly they take all the juice out of me, and I am thinner than usual and can barely stand and ask my daughter if I can hang onto her, and my son comes to my other side and we move a bit higher when we notice a car, an old-fashioned car for the year 1942, since it is a rich man’s car from the Packard or Hudson or Pierce Arrow days of fancifully named mechanical masterpieces, and outside the vehicle stands a veiled attractive lady, very dark because of her black triangular dress and her triangular hat, and she and her husband, surely a ruddy Irishman with panther eyes, are huddling around their Packard with its red leather interior, trying to coax sunrays against the black enamel of the doors to make them sparkle with purple haze like princess trees in the afternoon.

Under the couple’s feet the fields are violets as on an English king’s speckled overcoat, but they glance forlornly at us, and they are bored and we are penniless, which alarms me because we have come from a house, our big chic house, yet those horses, the perfectly tiny ones and the huge ones who look at us, seem to sap all my energy and wealth, though not my hunger to be alive, and I suppose that, being bored, the curious couple wants our company, and Tony tells me they have asked him if perhaps we would possibly like to eat with them, and my son says yes we would be delighted, and I am pleased because the horses leave me emaciated even though they are creations of grace and beauty, without cruelty or malice, with no desire to see us murdered by famine and poverty or so wasted that we can’t move.

So we all begin to walk, still with pleasure, up the hill while the horses remain in place, but there are always more good beasts ahead of us, greeting us with pleasant silence. I’ve turned as skinny as a child but am happy that they bring adventure and wonder into our existence until I recognize that we are rambling in another continent since right ahead of us are young Gestapo officers blocking our way, and they do not appear horrible as in the films and they have no intention to burn us alive or have us dig death pits and pop us off, one bullet per body, in our open graves, but it is not as if they want to speak to us about art and poets, which, after all, many Germans like to do when they remember good old days and the celestial imaginations of their syphilitic lyrical creators Hölderlin, Heine, Schubert, and Nietzsche.

Most prominent about the officers are their glimmering jackboots, not in strict goosestep, since wildflowers are stuffed just below the knee in their combat boots and petals are flittering in the wind and the knife-eyed SS can’t see these meadow wildflowers, nor the Tibetan vultures and Mongolian ponies nibbling funeral carnations also stuffed in their boots. Humming black hymns, the surrounding animals are busy burying bundles of boots together with funeral carnations in the sky and also right under the soldiers’ romping feet. In a flash the captains and lieutenants are naked, hairy all over fat bodies, their jockstraps stuffed in their mouths, and from their tiny brown penises hang bags of creamy foreskins and white scorpions. The sun turns into black sackcloth and the full moon into blood and the SS vanish like a scroll rolling up and disappearing beneath the Black Sea. But then in a flash everything is normal. The Tibetan vultures and the Mongolian ponies around the Nazi warriors disappear instead, the afternoon is its weird self, and the reclothed officers go on doing nothing in their regular shit-brown uniforms and glimmering jackboots.

Amid a few stone horses, Heinrich Himmler’s racially elite SS are in our way but they ignore us. The paramilitary death squads can’t see us. We walk through them as if through a wall. Perhaps our protector equines intimidated them, grabbed some of their powers and made us invisible too. The Einsatzkommandos in Poland are known for on-sight shooting of musicians holding their instruments and of painters holding their brushes yes in the middle of performance or creation or house-building, but for now one might suppose they are innocently confining their curiosity to looting famous paintings from museums and enjoying the sun. The off duty SS are horsing around on the meadows, letting go in slow motion, drowning in lager, unaware that invisible equine beasts are observing them and that in the future—in five years—the horses will perform their own withering nightmare attack on Einsatzgruppen executioners on the run from the law, in safehouses, in Berlin, Buenos Aires and Assunción, Paraguay, and that with Jehovah’s anger these equine demiurgic foes of the humorless brownshirts will spit out fire and abominations on the skulking boots, and inflict on them a trial, a cell, and a noose in Warsaw.

The casual loafing around outside a town, a major town in southeast Poland with a large Jewish population, does not seem to match the hidden snapshot of German command officers, and I hardly imagine that being cool and nonchalant can be the perfect uniform for SS (Gestapo) and SA (Storm Troopers), whose mission is execution. More, they keep good records, proving how commonplace they are when they are doing their job. Take SS captain Felix Landau, who will be of special interest. He writes in his diary about daily routine three months before our gang of five happen into his command terrain:

12 July 1941. At 6:00 in the morning I was suddenly awoken from a deep sleep. Report for an execution. Fine, so I’ll just play executioner and then gravedigger, why not?… Twenty-three had to be shot, amongst them … two women … We had to find a suitable spot to shoot and bury them. After a few minutes we found a place. The death candidates assembled with shovels to dig their own graves. Two of them were weeping. The others certainly have incredible courage… Strange, I am completely unmoved. No pity, nothing. That’s the way it is and then it’s all over… Valuables, watches and money are put into a pile… The two women are lined up at one end of the grave ready to be shot first… As the women walked to the grave they were completely composed. They turned around. Six of us had to shoot them. The job was assigned thus: three at the heart, three at the head. I took the heart. The shots were fired and the brains whizzed through the air. Two in the head is too much. They almost tear it off.

Who are those equine ghosts who drop us into the demon’s jaws? I don’t know. Are they salvific friends? I suspect them of fable. Somehow they come at a time of stupid slaughter by the brain-damaged Goths. I bought a book of short stories by a nameless Polish writer, who caused uproar in my blood and a primal walk into hell. Call him Bruno or Bronislaw or Bron. A child of passion from a mother who dies at his birth, Bruno Schulz possesses genius, he is a natural, but at the peak of his brief literary career, the Luftwaffe is air-bombing Poland brutally and Storm Troopers are black cobras spreading over the countryside, including Bruno’s birth town. Bruno writes and paints until his art vanishes on a whim.

But to be fair, the actors playing Gestapo in these scenes don’t invent terror. All religious scriptures are soaked in the blood of death squads upholding the faith. Death squads are the noble protectors, the enforcers for a sojourn of torture in hell, on the Buddhist walls of the Potala in Lhasa and in Dante’s cold chambers of the Inferno. In Rome, the Italian astronomer and mathematician Giordano Bruno dares to write that the earth circles the sun. Declared a heretic, Bruno is gagged and bound to a stake and he tastes papal fire in the Campo dei Fiori in Rome in 1600. In keeping with his noble precursors, my companion Bruno is a target of Gestapo fury; he is guilty of being a Jew.

My Bruno is real yet I see him as a birdman, a mythic condor with immaculate feathers made of lace clouds, who passes his years as the overhead watch eagle, an ancient dirigible below the clouds, who is the benevolent and beautiful master of all rosewood-colored horse deities in Poland, Belorussia, and Ukraine. But that is Bruno speaking, not me. The author is a temporal mortal born in 1892 in Drohobych, by the Ukrainian border, a town in the Austro-Hungarian Pale whose inhabitants are forty percent Jews, the remainder Poles and Ukrainians. Of the eighteen thousand prewar Jews, four hundred survive the multiple massacres. After the war they immigrate. The town is clean. In his youth Bruno studies architecture in Vienna, and thereafter remains in this Galician city that keeps changing name, nationality, border, and language.

Bruno comes from a family of assimilated Jews and, unlike the Hasids who stick to Yiddish, which is medieval Alsacian German, he composes in Polish, his household language. Modest Bruno—or is he Bron or Bronnislav?—evasive Bruno is black light and illumination. This high school art teacher is solitary and shows his stories to no one near him, but does write to a faraway secret reader, to a poet medical doctor in Lvov, Deborah Vogel, the bird. It doesn’t make him nervous to write secretly to a songbird he doesn’t know (he never tells his high school colleagues he is an author) and he composes, each mythic letter about his town and its orphans and its grandfathers, and his father, a fantastic scientist, who sits each night on the broad cobbled bricks at the bottom of the chimney and discovers and tracks threatening wild cosmic comets hurtling toward the earth. He warns people to stay at home until the sky dinosaur hits devastatingly on the planet or hops off into the infinite pleroma.

His pen pal Lily Vogel pieces his epistolary masterpieces together, encouraging him for more. She nourishes him with manna. Eventually, he gives his wisdom tales to a leading novelist who gives them to a publisher, and thereby his mythopoetic letters of unknown eccentric loners in a demiurgic world are published and to grand success. Critics say he is the best between-the-wars author. The Polish Academy of Literature awards him its highest prize and he is no longer alone but acclaimed by a coterie who threaten his solitude, yet he remains the hermit, the great heresiarch of central Europe. Even when the German troops enter and Polish writer friends give him false papers and money to escape, he does not escape from the ghetto where he is imprisoned with the other Jews, and his writing frees him from self-captivity. The same SS officer Felix Landau likes his drawings and paintings and protects him for a season.

Ich persönlich werde Ihnen eine Genehmigung zum Verlassen des Gebiets, sagte Laundau.

I personally will give you a permit to leave your area, said Laundau.

Ja, Bruno antwortete.

Yes, Bruno answered.

And Landau gives the teacher a permit to leave the ghetto and comes to his house and paints a grand mural for his children’s room.

By now Bruno is fifty, one year older than my father in 1942, and there is terror in the air and Bruno has no tiny or behemoth horses to take the energy or jackboots away from the ordinary SS soldiers who are slaughtering Jews in the streets, any Jew face they can find. That strange appearance and disappearance of the horses is ominous and comic like the high octave of Bruno’s tales and when the planet is collapsing the octave drops with tragic hilarity as when before a shower you kill a stray ant on the tub. As we walk I see that Bruno is my father, but I grow up in other continents, yet he is my father, and I am lucky to have him as a father, unlike Bruno who has a faraway fiancée and no children. But why feel sorry for Bruno the mythic visionary, who is not alone since no one is alone, and the recluse Bruno reads Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers, and knows what it is to be a kidnapped brother. The Pole adds many stories about quadrupeds, reptiles and birds to his collection and they crawl out of his collection into the meadows and bellow a secret music that deafens ears of even the friends he creates and the animals in the field fall asleep, yet in the end he weakens nobody who lives in his stories.

Bruno has written a novel called Messiah, which is of a man who is always a child, a youth on the earth whom we should emulate by maturing into childhood, but the boy is himself, not the heavenly messiah and therefore he is the earthly messiah, and Bruno entrusts all his papers to a friend, including his novel, just in case something happens to him.

My daughter and son and I keep walking, and we are glad that now we are a comforting group of five and there are all these tiny and big horses near us, though I wonder if they can truly protect us, and after all we aren’t Poles or Russians or from Ukraine and why would we need protection? But suddenly the horses start to disappear, the elephantine ones and the delicate ones, and their color remains in my eyes, and I regain my physical strength again, yet I realize that there is at last no hope for us, for any of us to tell this story, because all our rising meadow leads into a street and the street into a town, Bruno’s provincial town of Drohobych in southeast Poland, now Ukraine, and I remember with fierce intensity that my grandfather Michal was born in 1860 in Drohobych, finishes the yeshiva there before he floated over the Atlantic to Boston, and yes unlike sixteenth-century Bruno, who never is released from his dungeon, Bruno the art teacher has a protector and can leave the ghetto and paints and he isn’t burned alive. Nor is Bruno burned alive like all the Jews herded into huts and temples in the Ukraine, since my hero falls when he ventures outside his SS officer’s house to buy a loaf of bread, when a rival SS Kommandant jealous of his protection fells the philosopher Bruno in the street with two bullets to the head, and on this “Black Thursday,” 19th of November, 1942, there are another one hundred forty-nine Jews shot in the streets, and when I see the bodies I discover with disbelief and displeasure that my son and my daughter and even our rich hosts, who are to buy us a fine meal for sharing our company since they are bored and we are talking art and poetry, they are all lying on the street with me shot dead in my grandfather’s town, but fortunately one of Bruno’s good friends has seen the writer’s body and at night when no one is there takes the body and buries it in the Jewish cemetery, though the cemetery disappears along with the Messiah and all the other writings given to a writer friend because she too disappears like the rest, and the animals on the porch and the meadows and in the city streets begin to howl night and day, and, behold, later a museum is built by the Poles to house Bruno’s celebrated letters and whatever saved stories are found in magazines and his drawings and even remnants of the mural he painted for his protector the SS Einsatzkommando, and the Poles are good and honor the Polish violoncellist of the word Bruno as a visionary, their grand mythic fabulist in the decades between the wars, and hearing the animals still howling I am sad to be dead near him and sad that he cannot fulfill his myth of the novel, and infinitely more than sad it breaks my heart, I am heartbroken that Bruno can’t live a long life and waken us to the hermitage of a comic mind that is more cosmic than an orphanage on clouds, and if he had lived he would have unraveled the knot of the soul and informed us of the image, but Bruno knows that art must never assume a knowledge of revelation, only an ignorance that keeps us moving, that makes us go further inside and color the darkness, and isn’t that salvation enough? And so I am not that terrified or sad because I hardly know him when I start seeing the horses which my children think are goats or deer and that lead us to discovery, and we don’t seem now to be truly dead because I am telling you of a new voice, which is always wondrous to discover, and I am thrilled and hopeful, but know I am dead because we are also shot and we are lying very still with our beautiful hermit Bruno, the secret and solitary Bruno, whom I envy for his purity.

◆

Willis Barnstone, born in Lewiston, Maine, and educated at Bowdoin, the Sorbonne, Columbia and Yale, taught in Greece at end of civil war (1949-51), in Buenos Aires during the Dirty War, and in China during Cultural Revolution, where he was later a Fulbright Professor in Beijing(1984-85) Former O’Connor Professor of Greek at Colgate University, he is Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Comparative Literature at Indiana University. A Guggenheim fellow, he has received the NEA, NEH, Emily Dickinson Award of the PSA, Auden Award of NY Council on the Arts, Midland Authors Award, four Book of the Month selections, four Pulitzer nominations. His work has appeared in APR, Harper’s, NYRB, Paris Review, Poetry, New Yorker, TLS. Author of seventy books, recent volumes are Poetics of Translation (Yale, 1995), The Gnostic Bible (Shambhala, 2003), Life Watch (BOA, 2003), Border of a Dream: Selected Poems of Antonio Machado (2004), Restored New Testament (Norton, 2009), Stickball on 88th Street (Red Hen Press, 2011), Dawn Café in Paris (Sheep Meadow, 2011), The Poems of Jesus Christ (Norton, 2012), ABC of Translation (Black Widow Press, 2013), Borges at Eighty (New Directions Press, 2013).

Illustration by Ali Maidi.