Imprinted Cinema

IU Grad Student’s Film, Acetate Diary, screened at the Tribeca Film Festival ◆ by Brandon Walsh

Avant-garde cinema is uniquely equipped to engage with unspoken personal realities. Such is the case with Russell Sheaffer’s short experimental film Acetate Diary, an attempt to bridge the gap between individual trauma and a publically displayed medium.

[The image of Sheaffer at the top of this post is a promotional shot from the Tribeca Film Festival.]

◆

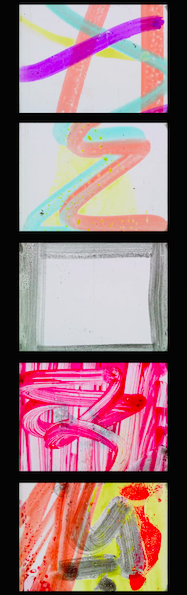

The film is an impressionistic scroll of abstract handmade patterns and shapes, indecipherable scrolling text, and broad strokes of color. The film is a visually impulsive exercise, modeling the diary films of Jonas Mekas and Sadie Benning as well as the nonrepresentational films of Stan Brakhage. An abstract expression, it requires the audience to tune their gaze to the film’s own visual logic.

Sheaffer acknowledges that the film is better experienced than discussed with language, which effectively alludes to the thesis of Acetate Diary. He says, “It’s tricky, because you’re articulating something that can’t be articulated.”

Selected Frames From Acetate Diary

◆

Sheaffer injured his jaw in a horrific accident involving multiple cars while driving on a San Diego freeway in November of 2012. Though surviving, the accident left him deeply affected. It wasn’t until a year later that he began to emotionally recover. “I just assumed I would get better … trauma happens, and you deal with that for a really long time,” says Sheaffer.

Not long after his recovery, Sheaffer’s world was upended once again. Given a troubling medical diagnosis related to the accident, he reverted to the same state of fear and disembodiment that he experienced following the accident. The night of his diagnosis, he ran into Susanne Schwibs, documentary filmmaker and faculty member of the Communication and Culture department. She says, “When Russell came to me with his idea for a handmade film, I was elated. It is a time-consuming process and so few people choose that technique. It is difficult, too, because what you see when you paint is not what you will see and hear when it is projected.” After discussing the leading events, Schwibs gave Sheaffer a spare developed 100-foot roll of 16mm film, which would become Acetate Diary.

While informed by the preceding year, the film itself documents the two week period of its production, manipulated in the analog edit bays in both the Communication and Culture department’s production lab and the lab made in Sheaffer’s basement. Schaeffer treated each day as a chapter in the diary, using different techniques and patterns, though the film was not produced sequentially. One day was devoted to laying his fingerprint on the film, others to sketching phrases and geometric patterns. The optical audio track aside the film was similarly modified. Sheaffer scratched the surface with a pushpin.

Still From Acetate Diary

◆

The result is a sculptural representation of cognitive emptying, a personal imprint on a physical medium. Schaeffer cites Orphans Midwest as a spiritual influence, a conference hosted by the IU Cinema consisting of handmade, “orphaned” films, of which he helped curate. Enrolled in Schwibs’ experimental film class, Schaffer was also exposed to the nonrepresentational films of Norman McLaren.

Sheaffer shipped the 16mm print to the FotoKem film lab for 35mm conversion, which screened at New York’s Tribeca Film Festival. Jon Vickers, director of the IU Cinema, assisted with the film’s conversion to film, “The long-term plight of digital preservation is still unknown. Russell now has a known, stable archival element that will surely last hundreds of years,” says Vickers. Acetate Diary screened in the festival as part of “Digital Dillema,” a series of 8 short films that explored the both endearing and fleeting qualities of celluloid film. “With so much going to digital, there’s a resurgence of films that are handmade that are one of a kind,” Schwibs says. It was also one of 9 student films shown in the festival.

The story of the film’s making is as equally captivating as the 16mm roll itself, and Schaeffer is aware of how the background will likely inform the experience of viewing the film. In either instance, he feels the message of discomfort comes across. “It should be a threatening encounter. It makes the work alive,” says Schaeffer. In essence, the value taken from Acetate Diary is as much dictated by the viewer’s own projection to the screen as the filmmaker’s.