Big Talk: Color Comics

Nate Powellʼs Drawings Bridge Divides ● by Michael G. Glab

[The Ryder and WFHB present Big Talk. This is the first in our new series of interviews with Bloomington people, conducted by Michael G. Glab. Hear Nate Powell speak with Glab on WFHBʼs Daily Local News. Send in your suggestions for future Big Talks to editor@theryder.com.]

■

How many people are celebrated cartoonists and big sellers in the graphic novel field? How many of them have created a DIY comic book publishing empire and then gone on to found a DIY record company? And how many of them toured two continents in a punk-hip-hop band?

Nate Powell, who fits all the above criteria, lives right here in Bloomington. And now Powell has become a spokesperson for the Civil Rights generation. Add to that the irony that heʼs white. Very white. He has pale skin and light hair. His features are sharp. He was born and raised in suburban Little Rock, Arkansas. Why him?

“People ask me why I am interested in civil rights or in human rights,” he says, after pondering the question a long moment. “Iʼm a person so naturally Iʼm interested in human rights.”

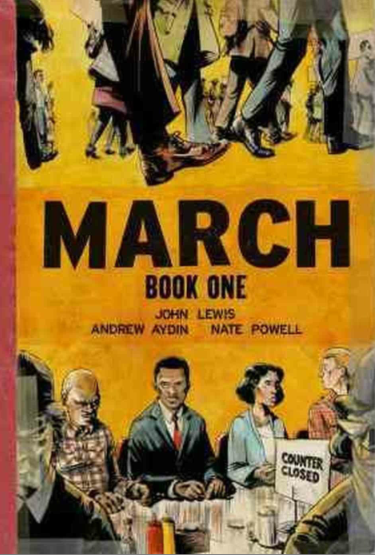

Civil rights are central to two of cartoonist Nate Powellʼs recent books; human rights to all his titles. His books, Any Empire and Swallow Me Whole launched him into the top ranks of the comix-memoir-biography-narrative-fiction field. And now, Powell has hit bookshelves again as the illustrator of March: Book One, the first in a trilogy recounting the life of civil rights pioneer and current Georgia Congressman John Lewis.

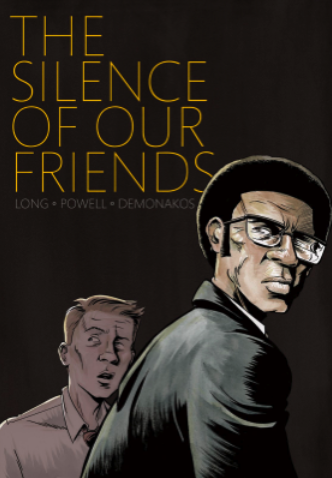

This on the heels of his 2012 release, The Silence of Our Friends, based on real events, about a black family and a white family in 1967 Houston who work together to win freedom for five black teenagers wrongly accused of killing a cop.

■

“Thereʼs been a strong social lean in my comics since Iʼve been an adult,” Powell says. “But Iʼd say it wasnʼt until five or six years ago that I felt Iʼd really had enough time and distance and perspective after leaving the south and seeing how more racist and backwards the northern midwest in a lot of ways is than the traditional south, to understand the different dimensions of American racism. I finally felt like a lot of my anxiety in terms of wanting to have something to say about race, power, and identity in our society, fell away. I wrote and drew some short stories about it. The authors of the Silence of Their Friends approached me about bringing their story to life. My work on that book got a nice big feature in The New York Times. John Lewis and his co-writer Andrew Ayden secured a publishing deal with my publisher, Top Shelf, for the book, March, but with no artist. They saw the New York Times review and were like, ʻOh, we should see whatʼs going on with this guy.ʼ But Iʼd already been speaking with my publisher who strongly suggested that I try out personally for the job. We all happened to find each other at the same time.”

Powell began his cartooning career as a high school freshman. “I started by drawing a lot of guns ʻnʼ boobs style superhero comics, as did many a 13-year-old,” he says. “My best friend and I had been drawing comics for a couple of years and we decided to take the jump into printing the books ourselves. At my dadʼs office there was, essentially, an unused copy machine and we decided we were just going to run off copies of our book until the thing broke down. Which is exactly what happened. We wound up with exactly a hundred copies of our first comic. We had exactly one comic book store in town at the time and the owner, who Iʼm still very much in touch with to this day, was gracious enough to give us a little bit of shelf space.”

The two teen publishers sank some of their own money into that first issue. “We wanted to have a full color cover. So, instead of bootlegging this whole thing for free, we paid a dollar for each cover.” It sold out, at $1.75 a copy. “We made five cents profit for each issue once the store took its cut. So with that nickel times a hundred copies, we had five dollars profit to split between us.”

They hadnʼt become publishing moguls but they were hooked. They put out five 32-page issues every two months. Each issue sold out. They learned tricks along the way, including how to cut galley pages and even how to work the old Kinkoʼs copy center counting card system to their advantage. Theyʼd become classic do-it-yourself entrepreneurs.

Around the same time, Powell and some friends decided to start making music. He performed live and on CD with a series of bands throughout his teens and into adulthood. He even started up his own indie, DIY label, Harlan Records.

“Publishing my own comic books irrevocably changed the way I look at life and the way I navigate the world,” Powell says. “A lot of steps along the way, whether it was drawing comics or publishing them, or being in a band or running a record label, a lot of it was just problem solving. It was realizing I didnʼt know how to do something and figuring out the little steps along the way, or making friends who all of a sudden had some insight.”

He ran off tens of thousands of comics in the ʻ90s. “My band, Soophie Nun Squad, started touring across the US and I would sell my comics and zines at shows. I also would writes columns and do illustrations for a punk magazine called Heart Attack out of California. But I was spending too much time photocopying and assembling these books — I was printing maybe 1400 of each issue — and could not save the money to step up and go to a real printer. So, I went to art school in New York in the late 90s, the School of Visual Arts, and I got a grant for a self-publishing project. I used that money to offset-print my first comic.”

Powell then set up a pro distribution deal. “That opened the door for me to get my books in comic book shops. That started in 2000.”

Eventually, Powellʼs career as a music executive was eclipsed by his graphic novel success. He explains: “From the time I was 2, pretty much, the only thing I wanted to do with my life was draw comics. That was certain. Things definitely got very serious as far as creating music and recording and touring with my friends but in a lot of ways we took a personal and creative stance against trying to make a career out of it. And, really, our band was sort of too weird and full of too many people, full of too many conflicting ideas to ever be successful. Soophie Nun Squad was sort of a ten-piece punk, hip-hop,n Muppet Show band, with costumes and occasionally puppets.”

Music from Powellʼs bands as well as that of bands his label issued can be found online.

Now, Powell continues working on the March trilogy as well as some other big-time projects. Itʼs not all that easy as just dashing off pictures in the snap of a finger, especially when Powellʼs illustrating a book written by others. “There are a lot of different ways to write a comic book script,” Powell says. “When I write and draw my own books, I donʼt even use a script. Iʼll have the big idea that I want the book to be about. Then Iʼll have a series of events, little vignettes, that I spend a couple of years rearranging and building a relationship between characters and events. Then itʼs a longer process of waiting for characters to emerge, from inside, that you actually care about. I know how a storyʼs going to be paced. I know how long itʼs going to be, but in terms of dialogue and text, that really comes out while Iʼm pencilling.

■

“My own stories are much more fluid and intuitive. Andrew and Johnʼs script was a classic, finished, comic book movie script, divided into scenes, panels. Originally, March was going to be a single graphic novel about 160 pages long. Within a couple of pages I realized that we were dealing with a 500-page book, just based on wanting to take the reins with my own narrative sensibilities, pulling out different focuses.

“A lot of it had to do with John Lewisʼs internal landscape as a person, but also as a character within this book. A lot of it had to do with looking in between the lines of the script and seeing what wasnʼt evident in the text. In Book Two, we cover the Freedom Rides. When John Lewis and other Freedom Riders are pulling into the Montgomery, Alabama, Greyhound station, something appears very wrong because there are only two or three journalists standing around, itʼs very still and very quiet. They know things are about to go horribly wrong, but they donʼt know when, how, from what direction, or who these people will be. So there might be this five-second window where everyoneʼs quiet, everythingʼs still, and then everything goes to hell.

“From my narrative standpoint, that is the scene, that five seconds. So itʼs a matter of turning that from one panel into two and a half pages. A lot of the fun and power of comic book storytelling is this control of time.”

March: Book Two is due to hit bookshelves around Thanksgiving. March Book Three should come out in the summer of 2016. Meanwhile, Powellʼs also working on another, albeit different kind of book. Heʼs currently inking panels for a spin-off of the wildly popular Young Adult novelist Rick Riordanʼs Percy Jackson series, entitled Heroes of Olympus. That graphic novel is in production and will be released in 2014.

Powell squeezes in drawing during nap times for his and his wifeʼs two-year-old daughter. Heʼs lived here in South Central Indiana since 2004 after tiring of living along the East Coast. Heʼd fallen in love with Bloomington after visiting here several times while on tour with Soophie Nun Squad. Plus, a good friend had gone to school here and had settled in Bloomington. “Here I am,” he says. “I love this town a lot. I have no plans to go anywhere.”