Peasant Happiness

Celebrating the Cultural Revolution in China ■ by Molly Gleeson

It all started with a phone call. “Do you want to go to Peasant Happiness with my mother this weekend?” my friend Marsha asked. I thought perhaps this was the greatest oxymoron I had ever heard. “What,” I asked, “is Peasant Happiness?”

“It’s a place that celebrates the Cultural Revolution,” she said.

“But Marsha,” I said, “wasn’t the Cultural Revolution a really terrible time for China?”

“Oh, it was really bad for the country, but for individuals it was really quite fun,” Marsha said.

■

This is the same well-educated, well-traveled woman who said to me when I balked at “registering” at the local police office, “It’s just so if anything happens to you you’ll be treated like a citizen.” I said I wasn’t sure I wanted to be treated like a citizen. In any case, I wouldn’t go to Peasant Happiness that weekend, but Marsha had put it in my mind and I was curious.

I convinced my student friends Alice and Ida to join me one spring weekend to visit one of these Peasant Happiness’s, just outside Chongqing. We took a bus and then motorcycle taxis up a mountain and arrived around 9: 00 p.m. There are hundreds of these places in China, and dozens of them around Chongqing. However, only a handful of them have the Cultural Revolution as their theme. This one was called Longjishuanzhuang or “The Spine of the Dragon Peasant Happiness.” We met the manager, the indomitable Mrs. Luo. She told us this that “old intellectuals who worked on farms during the Cultural Revolution” pass through its gate every week. Indeed, from looking around it seemed that most people there that weekend were between the ages of 50 and 70. I certainly was the only laowai (foreigner) and Alice and Ida seemed extremely young in this company. Most people would only stay a night or two, watching a performance about the Cultural Revolution one night and playing mah jong the rest of the time. Mrs. Luo said these old-timers come here to “remember history and to renew their memory” and although they were “tough times” it makes them “appreciate what they have now,” she said. Over a meal of preserved duck eggs, sour vegetable and fish soup, egg and tomato soup, fried corn kernels and a local vegetable known as kongxin cai, Ida proclaimed: “I think these people come here because the food is very delicious.”

We got a room to ourselves, and proceeded to play mah jong. I was getting pretty good at it. When we got tired of that Alice and Ida borrowed my camera and took endless pictures of themselves while I read Anthony Trollope’s Phineas Finn. The next morning my friends got up early to explore the place and then came to wake me up. It was Friday morning and the place started to fill up. We took a walk around the grounds – full of fruit trees in bloom and a spectacular view of the Jialing River and the district of Shapingba beyond. There was a large pagoda with tables for mah jong along this route. A group of older people were already hard at it. We were curious about them, and they were a little curious about us. We weren’t the average visitors to this place. I asked one of the men, a Mr. Xu, why he was here. “We’re here to honor our memories,” he said, and added, “We’re here to remember and celebrate our youth.”. Mr. Xu is 58. He said he and his friends go to different Peasant Happinesses every month. He said they were teenagers during the Cultural Revolution, and were sent to work in China’s burgeoning natural gas industry. Mr. Xu’s education was delayed ten years because of the Cultural Revolution. However, he considers himself “very patriotic” and is proud of what he and his friends did for China. Mr. Xu admitted that Mao Zedong made a mistake with the Cultural Revolution, but that he was still a great leader. He went back to playing mah jong. So did we. I won three times in a row.

Later I went for a massage, a service provided on the grounds of this Peasant Happiness. I attracted quite an audience. The masseuse assured me that it could help me lose weight. I thought, well, it sure beats exercise.

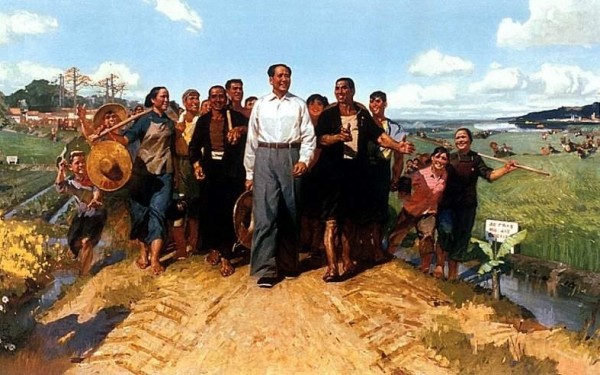

That night was the performance. I counted on my friends to translate for me, but they had a difficult time of it because it was all in Chongqinghua, the local dialect. The show began with the entire cast, all in Red Guard uniforms, singing popular songs of the time. The audience was encouraged to join in on “All the Members are the Flowers Facing the Sun” and “A Song for Zhiqing” (“Young Members of the Community”). The emcee for the evening said that the performance was meant to “remind us of the Cultural Revolution”. The players chanted that the purpose of the Cultural Revolution was “to fight against the imperialists and to build China like Mao said.”

The performance went through the various stages of the Cultural Revolution. There was an actor praising Mao but it was difficult for my translators to grasp. There was a story of a young girl, forced to marry the feudal lord’s son because her father had no money for taxes. There were scenes of “materialists” being punished. One poignant scene was a teenage girl having to leave her parents to go work in the countryside. An audience member walked up on stage and presented the actress with flowers. Anytime an audience member was moved, they would go up on stage and give flowers to the actors. Plastic flowers were provided in front of the stage. I thought if there was one thing many of these audience members could relate to, it would be leaving their parents to be “re-educated” in the countryside. The performance soon ended, with rousing songs and flags flying. They marched through the audience. And then the disco lights came down and there was a “dance party”. We didn’t stick around for it. I went back to reading about materialists and imperialists in Phineas Finn.

■

Karl Wu, who owns a bar in Shapingba, has gone to many Peasant Happinesses. He was only a child when the Cultural Revolution happened, but he does remember that his parents sent him to live with his grandparents in the countryside because the situation in Chongqing was precarious. Wu said he doesn’t agree with the politics of the time, but goes to these places because he wants to re-live his youth. He said young people today don’t know the history of the Cultural Revolution, and they should. He said Mao is “like a god in our minds.” People don’t think of him like that anymore, however, he added. ”It’s not to say he didn’t make mistakes, I’m not saying that, but he is the most important person in recent Chinese history.”

I contacted Dr. David Arkush, a professor of Chinese history at the University of Iowa. I asked him if he thought it was weird to “celebrate” the Cultural Revolution in this way. He said he could understand it because people have a need for nostalgia, and that was certainly what Peasant Happiness was all about. In spite of the terrible things that went on during that time, he said it was a more innocent time. There wasn’t the corruption that there is today, he added. There wasn’t the disillusionment. He said it was great for young people – they got to travel when no one was traveling. They got to see some of China and to try new things.

Alice, Ida and I stayed until the next day. We tried to get lunch, but Mrs. Luo said it was only for the groups that came and we weren’t part of a group. So we left. As we were leaving some of the workers there told us that we had been cheated badly – we were charged separately for our room and for meals, when everyone else just paid one fee. This fee was considerably lower than what we had paid. Laowai beware. We took a bus down the mountain and back to our lives.

■

The Ryder, January 2013