Magic Steeped In The Real

The Legacy of Gabriel Garcia Marquez ● by Will Healey

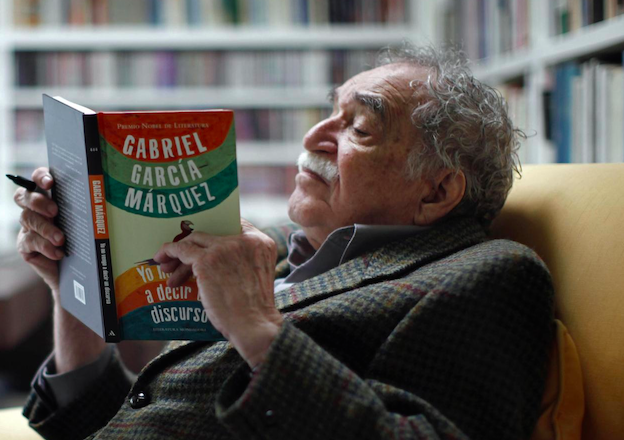

When Gabriel Garcia Marquez died in April at the age of 87, the literary world lost a giant. The man best known for his 1967 masterpiece One Hundred Years of Solitude and the literary genre with which his name became synonymous, magic realism, left in his wake a trove of novels, short stories and essays that simultaneously communicate timeless truths of life and evoke the mysteries of the supernatural.

Garcia Marquez, from Colombia, was the most celebrated Latin American writer of his era, and one of the most revered writers of the last fifty years. So towering were his works, that when he received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982, the Swedish Academy of Letters said “Each new work of his is received by expectant critics and readers as an event of world importance.” Writer William Kennedy famously called One Hundred Years of Solitude “the first piece of literature since the Book of Genesis that should be required reading for the entire human race.” Telling a friend that I was finally going to read that novel after Garcia Marquez’s passing, he said, “it’s the history of the world told through the story of one family.”

Garcia Marquez started his career as a journalist, but gravitated to fiction in his thirties. He had many celebrated works besides One Hundred Years of Solitude – his novel about a 50-year unrequited love, Love in the Time of Cholera; the short story collection The Leaf Storm; a tale about the epic reign of a fictional Caribbean dictator, The Autumn of the Patriarch; and News of a Kidnapping, a non-fiction book about a series of kidnappings carried out by Pablo Escobar’s Medellin cartel.

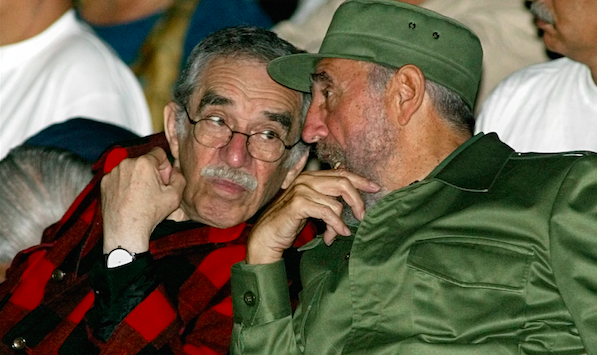

Garcia Marquez’s works were very much influenced by the times in which he lived, and he was unapologetically political. He counted among his friends Fidel Castro and Bill Clinton, and was outspoken in his disdain for Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet. Jonathan Kandell, in a piece for The New York Times marking the death of the great author, wrote that Garcia Marquez’s work “sprang from Latin America’s history of vicious dictators and romantic revolutionaries, of long years of hunger, illness and violence.” Kandell went on to quote Garcia Marquez’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech: “Poets and beggars,” Garcia Marquez said, “musicians and prophets, warriors and scoundrels, all creatures of that unbridled reality, we have had to ask but little of imagination. For our crucial problem has been a lack of conventional means to render our lives believable.”

In some literary circles, however, Garcia Marquez was criticized for the fantastical elements in his writing, something Salman Rushdie (on whom Garcia Marquez’s work had a great influence), took issue with in a New York Times piece written shortly after the author’s death. Rushdie wrote that the fictional village of Macondo, the backdrop for the agonies and ecstasies of seven generations of the Buendia family in One Hundred Years of Solitude (modeled after Garcia Marquez’s north coastal Colombian birthplace, Aracataca), was similar to William Faulkner’s fictional Yoknapatawpha County in Mississippi. Rushdie used the comparison to argue that Garcia Marquez, like Faulkner, created real characters inhabiting a real world.

“The trouble with the term “magic realism,” is that when people say or hear it, they are really only hearing or saying half of it, “magic,” without paying attention to the other half, “realism,” Rushdie wrote. He goes on to say that if magic realism were just “magic,” then it wouldn’t have much effect on the reader. Because anything is possible, the stakes are lower. But, Rushdie says, when the magic is “rooted in the real, and is brought in to supplement the real, that’s when the fun starts.

Rushdie describes a famous scene from the novel, wherein a character dies from a single gunshot and a trickle of his blood leaves his house and serpentines up and down through the streets of Macondo until it finally stops at his mother’s feet. According to Rushdie, the passage “reads as high tragedy,” because the impossibility of the blood’s purpose-fueled behavior, juxtaposed against the plausible event of a mother learning of her son’s death, takes on a higher, even spiritual meaning. As Rushdie puts it, “The real, by addition of the magical, actually gains in dramatic and emotional force. It becomes more real, not less.”

In another notable scene from the novel, the death of the patriarch of the Buendia clan, Jose Arcadio Buendia, is marked by a steady rain of tiny yellow flowers, so many that the next day “the streets were carpeted with a compact cushion and they had to clear them away with shovels and rakes so that the funeral procession could pass by.” Jose Arcadio Buendia led the expedition that founded Macondo, and was a polymath of boundless energy. His unquenchable thirst for knowledge ultimately drives him mad, but the solemn poetry of the raining flowers suggests that the heavens were paying tribute to a man who gave everything to try to advance the lot of his people.

True to Rushdie’s sentiments that the power of Marquez’s work lay in the real, I’m struck that the passage that had the greatest effect on me in One Hundred Years of Solitude didn’t contain anything fantastic or unexplainable. Albeit tragic, masterfully written and heart-wrenching, this passage simply depicts a man’s final moments.

“On the way to the cemetery, under the persistent drizzle, Arcadio saw that a radiant Wednesday was breaking out on the horizon. His nostalgia disappeared with the mist and left an immense curiosity in its place. Only when they ordered him to put his back to the wall did Arcadio see Rebeca, with wet hair and a pink flowered dress, opening wide the door. He made an effort to get her to recognize him. And Rebeca did take a casual look toward the wall and was paralyzed with stupor, barely able to react and wave good-bye to Arcadio. Arcadio answered her the same way. At that instant the smoking mouths of the rifles were aimed at him and letter by letter he heard the encyclicals that Melquiades had chanted and he heard the lost steps of Santa Sofia de la Piedad, a virgin, in the classroom, and in his nose he felt the same icy hardness that had drawn his attention in the nostrils of the corpse of Remedios. “Oh, God damn it!” he managed to think. “I forgot to say that if it was a girl they should name her Remedios.” Then, all accumulated in the rip of a claw, he felt again all the terror that had tormented him in his life. The captain gave the order to fire. Arcadio barely had time to put out his chest and raise his head, not understanding where the hot liquid that burned his thighs was pouring from. “Bastards!” he shouted. “Long live the Liberal Party!”

Marquez (L) And Fidel Castro

●

Garcia Marquez did not invent the genre of magic realism, but he certainly popularized it. Countless writers today employ it in their work- Rushdie, Isabel Allende, Haruki Murakami, and Toni Morrison, to name a few. His influence carries over into other media as well. Watching the film Pan’s Labyrinth, which juxtaposes a strange world of mythical creatures against the harsh realities of the Spanish Civil War, it’s hard to imagine Mexican director Guillermo del Toro wasn’t influenced by Garcia Marquez. Or take the famous raining frogs sequence in Paul Thomas Anderson’s 1999 film Magnolia, which depicted the mysterious intersections of seemingly disparate lives. What makes Magnolia’s famous sequence work isn’t that the events in the film are so coincidental that, sure, frogs falling from the sky isn’t so far fetched; it’s that the characters that are all strangely connected are so real to us, and the dramas that play out in their storylines so human, that the frogs falling from the sky is an inexplicable moment of wonder that somehow rings true – Garcia Marquez’s personal recipe for successful, affecting magic realism.

Just four months on from his passing, and 47 years after the release of One Hundred Years of Solitude, it is still far too early to fully measure the scope of the author’s impact on the world. But back in April, when it became known that Garcia Marquez had finally succumbed to complications from lymphatic cancer and dementia, I wonder how many of his admirers checked outside to see that there weren’t yellow flowers raining from the sky.