▼

Filmmaker and visiting lecturer Monika Treut explores sexual and gender identities of the under-represented. A retrospective of her work will be presented at the IU Cinema October 22-24 ◆ by Filiz Cicek

Before there were male gods, there were fertility goddesses, bare-chested priestesses. In time the Amazons were defeated. Pagan priestesses were burned at the stake in Spanish Inquisitions. The male Greek god of fertility, Pan, would become the most ubiquitous devil. Once a symbol of renewal, the serpent would evolve into Eve’s slithering aide as she bit into a forbidden apple. The biblical female, the first mother, is forever guilty of knowledge. Adam had no will power against his temptress sinner, born of his own rib. Adam did not have an Adam, Eve did not have an Eve.

■

Whether mothers or prostitutes, women on the silver screen function as body projections of patriarchy’s fears and desires–bodies to be to objectified and demystified from the male gaze. “Torture the blondes,” Alfred Hitchcock said. And in Vertigo, he killed not one, but two blondes: the wife and the hired mistress, for they tortured the male anti-hero Scottie with their sexual allure and deceptions. In Hollywood cinema, the female character aids the male hero in his quest to greatness. In melodramas she is given temporary agency, a parenthesis in time so to speak, to be the main protagonist who furthers the narrative in the absence of the strong the male character, whose masculinity is in crises. She is forced to explore her whorish persona, usually by being a nightclub singer or a prostitute in order to provide for her nuclear family.

Soap operas, too, follow this binary formula: housewife and villainess. Her ability to assert her independence comes with a social stigma. From Mexico to Berlin, from Istanbul to Delhi, the melodramas have been telling us that a woman who sins, who is sexually promiscuous and disobeys the norms must die or become a mother to redeem herself.

Binary explorations of female sexuality are rooted in Judeo-Christian traditions among others. The absence of Mary Magdalene and Madonna in non-catholic churches in America is a testimony to our Puritanical history. Yet in the midst of all this, a man named Alfred Kinsey, a scientist studying insects, set out to study human sexuality. With the support of Herman B. Wells, and fellow scholars, he established The Kinsey Institute.

Professor Brigitta Wagner, who teaches German Cinema at Indiana University, saw a natural German connection with The Kinsey Institute. She considers Kinsey’s work the continuum of German scientist Magnus Hirschfeld. An atheist and a homosexual, Hirschfeld founded the Scientific Humanitarian Committee in Berlin in 1897 in order to defend the rights of homosexuals and to repeal Paragraph 175, the section of the German penal code that since 1871 had criminalized homosexuality. Hirschfeld believed that a better scientific understanding of homosexuality would eliminate hostility toward homosexuals. He then established the Institute for Sex Research in Berlin in 1919. Hitler declared him the most dangerous Jew in the world. The Institute was destroyed and its archives burned in 1933. Nevertheless Hirschfeld’s work inspired scientists, artists and filmmakers, including Alfred Kinsey.

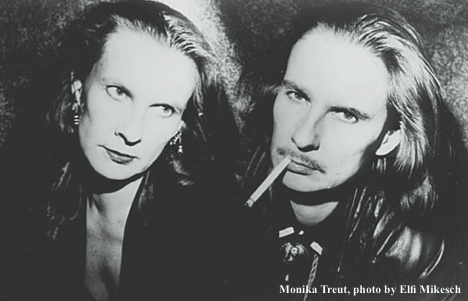

Wagner invited the openly lesbian German independent filmmaker Monika Treut as a Max Kade Fellow to teach a course in collaboration with The Kinsey Institute on human sexuality in film. Treut’s students are learning about both Magnus Hirschfeld and Alfred Kinsey’s work and looking at the construction of sexuality and gender in a number of European films, as well as in The Kinsey Institute’s film collection. “Students will explore this historical visual material that documents human sexual desires and expressions,” explains Liana Zhou, the head curator for the film archive. In doing so she is hoping that “the students will be able to provide social, cultural, historical, and artistic context to these unique examples of early erotic film to their audience after almost hundred years since these films were produced.”

Originally a scientist who set out to study insects, Kinsey began to study human sexuality only after getting married. Before him, Germans had fought for the rights of the “third sex” with films like Different From Others (1919). These films came to a halt in the 1930s with the rise of the Nazi regime.

In American in 1934 the Hayes Code purified the silver screen. Gays, lesbians and strong female characters were among the casualties. Gone was May West shooting a gun at train robbers and coyly inviting Cary Grant, the chauffeur, to “come up and see me some time.” When Kinsey began his research, Donna Reed, Lucille Ball and Doris Day were all sleeping in separate beds from their husbands in their on-screen bedrooms.

Depictions of lesbians on screen were so subtle as to render them invisible. Much later, lesbians, like their gay male counterparts, would be portrayed as self-hating villains. As in heterosexual melodramas, death by redemption remained the norm.

In 1959, Billy Wilder, an Austrian born German-Jewish Hollywood director, experimented with gender identity in Some Like it Hot, with Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon dressed as female musicians. William Wyler followed in 1961with The Children’s Hour, a drama exploring the budding sexual preferences of two housemates played by Shirley MacLaine and Audrey Hepburn. MacLain has reflected back with amazement that she and Hepburn have never discussed the topic openly, even while shooting the film.

We have come a long a way since then. The lesbian characters in cinema, independent cinema in particular, are not as incidental. LGBTQ film festivals are held across the globe. Yet it will be a while before Titanic becomes a love story between two women.

◆

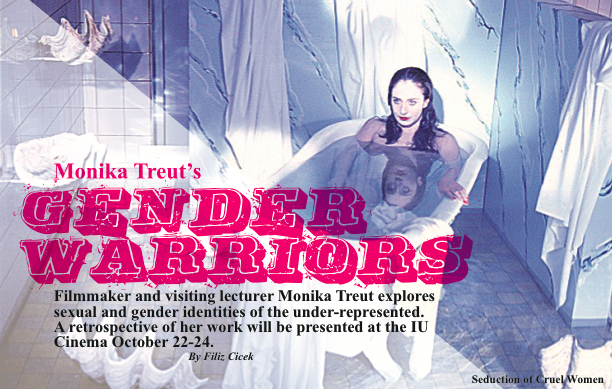

Treut Films: Seduction of Cruel Women

Since her directorial debut, Treut has been exploring sexual and gender identities of the under-represented, including lesbian, transgender, and transsexuals. Treut’s female protagonists are most often the strong ones, in charge of their own lives. Unlike Hitchcock’s blondes, Treut’s “cruel women” torture men—and men are willing slaves to their female tyrants.

In Seduction of Cruel Women, women take turns as the tortured and the torturer. Having written her PhD thesis on masochism, Treut explores sadism as well. “Visual art nourishes masochistic desires and emotions,” she explains. In Cruel Women Treut converts an abandoned building in the Hamburg docks into the “Gallery,” a studio for sexual exploration. The set-design recalls oil paintings in the 16th Century style of nature-morte. Instead of fruits and bowls and dead rabbits and pheasants, you have fetish objects, furs and shoes. Lights and colors—a palette from white to red to black—reflect the desires and fears of characters who are seeking to dominate or be dominated. Treut explains, “it is often the powerful man who wants to be dominated.”

◆

Gendernauts

Judith Butler defined gender as performance. Sandy Stone, “Goddess of Cyberspace” in Treut’s 1999 documentary film Gendernauts agrees: “Gender as performance is a series of signals we send to each other. How do we change ourselves and those around us, by moving from a narrow space to a larger one, to a space of greater psychological distance eventually ending up in a situation that invades the space that of the other?” But not all gendernauts concern themselves with identity, “and gender confusion is a small price to pay for social progress.”

But Treut is not a fan of this approach to identity. “In this country,” Treut explains, “people define themselves through their sexual orientation. They make a real strong point when they say ‘I am a lesbian.’ They think they have a concept for life, for a relationship. I don’t agree with that…we are more than our sexual orientation.”

■

Female-to-male transgender artists and performers, Texas Tom Boy and Max Valerio, explain why they chosen hormone therapy. Based in San Francisco, they perform their new identity both as artists and people. Receiving regular testosterone shots, Valerio had explored lesbian relationships before deciding that it is the traditional, heterosexual dynamic what he wants in a romantic and sexual relationship. And he wants to be the man. Charged with newly found energy, Valerio embraces his heightened sexual drive from testosterone. Valerio no longer cries and wants to be physically stronger than his female partners.

◆

Female Misbehavior

Treut takes on the “decade of feminism” (mid-1980 to mid-1990s), including its anti porn stand. Female Misbehavior features Camille Paglia and Annie Sprinkle. Dr. Paglia’s inclusion in the film was controversial due to her blunt criticism of feminist scholarship. Paglia, with the flair of a stand-up comedian more than an academic, describes her critics as religiously oriented with a social agenda that lacks art, beauty and aesthetics. “I am bringing beauty back in to feminism,” she declares—“like Madonna.” More in love with regal and majestic Egyptian art than humble, turn-your-other-cheek Catholicism, she declares, “I am an Aries. War and conflict is my natural state, and this is how we come to find and define our identities.”

◆

Warrior of Light

Not all of Treut’s characters are gender warriors. Often preferring real life stories to fiction, Treut travels to Brazil with Warrior of Light. In the midst of a ghetto in Rio, a woman runs Children of Light, a project committed to the protection and the education of poor and abandoned street children who are mostly of African descent and HIV positive. Artist turned activist, Yvonne Bezerra de Mello has a middle class background and was prompted to take action after a shocking police massacre of street children 1993. In a country where poverty is rampant, the wealthy see these children as nothing but thieving savages. De Mello, who was educated in the Sorbonne, has no illusions about ending poverty any time soon. Many of the children are descendants of African slaves with no records, papers, no sense of self and no love. She has three rules for her children: No drugs; no guns; no Bible.

■

A retrospective of Monika Treut’s work will be screened at IU Cinema from October 22nd through the 24th. She will host her students’ selection from The Kinsey Institute film archive on the 25th. So in the spirit of Hirschfield and Kinsey, and gender warriors and strong women everywhere, you are all invited to be a gendernaut temporary, permanent or otherwise, by Cyber Goddess Sandy Stone: “Join us, join the identity party, join the excitement, the challenge and the stark terrifying fear of playing in the boundaries between identities!”

The Ryder ◆ October 2011

▲

Comments

One response to “FILM: Monika Treut’s Gender Warriors”